Highlights

- Normally, this percentage of young adults still living with mom and dad hovers a touch above 40%, but it came close to half at the height of the pandemic. Post This

- Marriages and divorces both fell in the early months of the pandemic. Interestingly, measures of marital contentment also rose in 2020, raising the possibility that some divorces were averted altogether. Post This

COVID-19 cases and deaths are declining, and we are fast approaching the point that everyone who wants the vaccine has it. Adults are getting back to work—despite a disappointing jobs report this month—and most schools are, at minimum, planning to be fully open in the fall.

It’s not a bad time to take stock of what the pandemic has done to families and how far we still need to go for a full recovery.

1. No School

For Americans with kids, school closures have been one of the most frustrating aspects of the lockdowns. And many schools are still not fully in-person.

Several different groups have tracked school closures, using different measures, and things have clearly improved since the winter. The American Enterprise Institute, for example, classified 28% of schools as fully remote and another 40% as hybrid at the beginning of the year—numbers that shifted to 48% hybrid and just 2% fully remote by early May.

The most recent data from Burbio, meanwhile, hold that 3% of kids attend online-only schools, while another 29% attend hybrid schools that don’t offer a fully in-person option. Back in early January, Burbio estimated that an outright majority (53%) of kids were in virtual-only schools, with another 15% attending hybrid schools.

Either way, fully online school was quite common over the winter, and lots of kids are still stuck in hybrid. Unsurprisingly, keeping kids out of school has resulted in learning loss: Grades and math scores are down, attendance is poor, and some worry the damage will be long-lasting. School closures have also kept parents, especially mothers, from working.

2. Less Work

Speaking of working troubles, people have also been thrown out of jobs by business shutdowns and customers staying home out of fear of the virus. Too many families have seen a mom or dad lose a job or be forced to stay home from work.

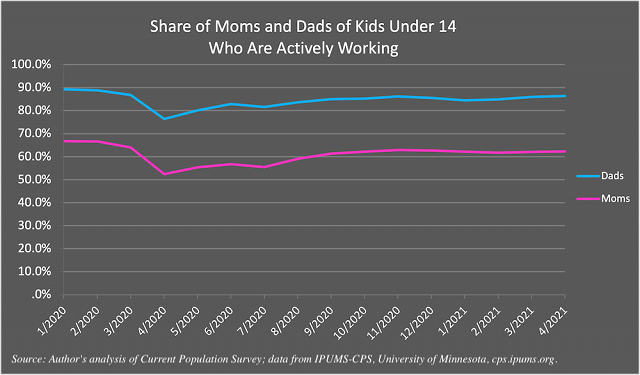

In March, I wrote about a Census report covering trends in parents’ “active” work status, meaning it doesn’t count if someone has a job but is on leave. With a few more months of data, I can update the trends in that variable. Where the Census included all parents of “school-age” kids (ages 5 through 17), this chart shows the trend for parents with any kids under 14 in the household, as some day cares closed and older teens are often mature enough to do virtual learning home alone.

In these families, both moms and dads are still out of work at higher rates than they were beforehand, with moms lagging a little more.

3. Young Adults Back in the Nest

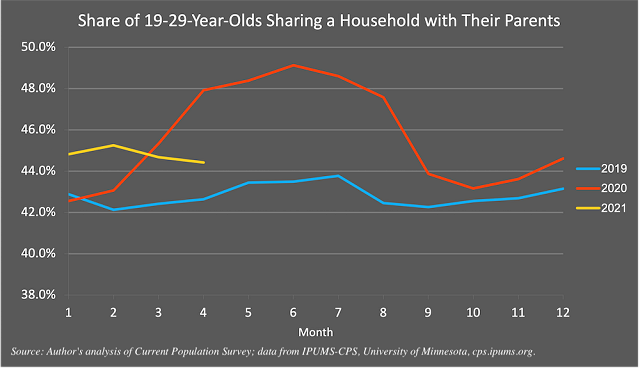

Census data also allow us to measure what percentage of 19- to 29-year-olds share a household with at least one of their parents. (Pew did a similar brief last year, but it included 18-year-olds, who in the early months of the year have often not yet finished high school.) Normally, this number hovers a touch above 40%, but it came close to half at the height of the pandemic.

Note that this does not capture the effect of college kids leaving the dorms to attend school from their parents’ basements, as kids living in dorms were already considered part of their parents’ households for these purposes. So the true increase is a bit higher, as many colleges shut down in-person instruction the same way K–12 schools did.

4. Less Marriage and Less Divorce

Unfortunately, national statistics on marriage and divorce are hard to come by, at least in the near-term. But the virus led to the rescheduling of many wedding ceremonies—I attended a wedding this month that was supposed to happen a year ago—and made it trickier to handle the logistics of divorce. COVID also kept potential couples from meeting and added a lot of stress to marriages, which could create longer-term effects.

A study published in April put together divorce and marriage numbers for a handful of states with available records. Marriages and divorces both fell in the early months of the pandemic, and they didn’t fully rebound in some states, leaving a “shortfall.” Interestingly, measures of marital contentment also rose in 2020, raising the possibility that some divorces were averted altogether. We’ll know more as more data come in.

5. No Relief from Declining Birth Rates

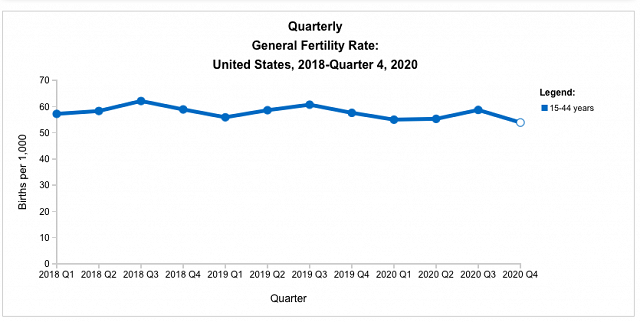

Birth rates have fallen steadily in recent years. Some hoped that the lockdowns might produce a baby boom as couples found themselves locked inside with nothing better to do. The Institute for Family Studies’ Lyman Stone forcefully argued against this theory, however, and the data are starting to bear him out.

Since it takes roughly nine months to have a baby, conceptions from March 2020 don’t show up as births until around December, but the CDC’s provisional fourth-quarter 2020 birth data show a record low for the fourth quarter of 2020, down more than 6% since the final quarter of 2019 and continuing a decline that started with the Great Recession.

Source: CDC

As with marriages and divorces, we’ll have a better idea when more data come in. But for now, at minimum, it looks like the March lockdowns didn’t cause any type of baby boom.

Across many domains, COVID-19 did real damage to family life. The extent of that damage is only slowly coming into view.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.