Highlights

- Even in normal times, women do more work at home while men do more paid work, so when a virus sends kids home from school, there’s a similar gender skew in how families choose to deal with the change. Post This

- Between January 2020 and January 2021, moms living with other working-age adults actually suffered much less damage to their employment. Post This

By at least one important measure, moms’ and dads’ work lives are getting back to something resembling normal.

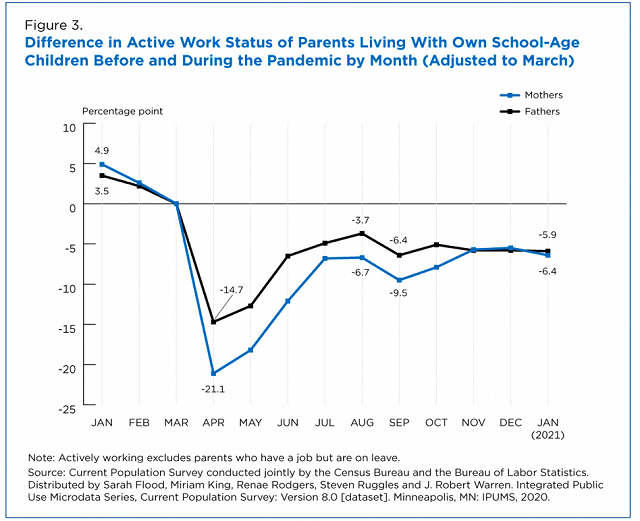

When COVID-19 really started to take its toll on America in April of last year, both parents were thrown out of work in alarming numbers. In normal times, about 70% of moms and 90% of dads are “actively” working (meaning it doesn’t count if they have a job but are on leave). But in April 2020, the numbers dropped about 15 percentage points for dads and an astounding 21 points for women. Unlike most recessions, this one hit women hardest.

By November of last year, though, the trends started to look less gendered. From then through January (the last month for which data are available), both moms and dads were actively working at rates about six points below their old normal, according to a new analysis from the Census Bureau.

As health-care professionals keep sticking needles into arms—and hopefully these numbers and others start looking even more like they did in the Before Times—trend watchers need to be asking both backward-looking and forward-looking questions.

The backward-looking questions focus on what happened during the pandemic’s worst months and why. For one: Why were women so much more likely to stop working?

As the Census researchers note, there are two big explanations. One, female workers are highly concentrated in some of the jobs that were hardest hit. And two, even in normal times women do more work at home while men do more paid work, so when a virus sends the kids home from school, there’s a similar gender skew in how families choose to deal with the change.

In a recent paper released through the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), two economists pointed out that “women are overrepresented in [the] high-contact and inflexible occupations most affected by the pandemic. While these occupations account for 15% of total employment, 73% of workers employed in these jobs are women.” Like the census researchers, they found that women—especially moms—saw particularly big employment declines during the pandemic, but they report that “controlling for occupations attenuates the gender differences in employment losses by about one third,” at least in the spring and summer when the economic damage was most severe.

As any parent who’s lived through this mess can attest, school closures mattered, too. A paper forthcoming in Gender & Society looks at the gender gap in parents’ labor-force participation in 26 states with available data. Between 2019 and 2020, this gap grew much more in states where schools were mostly remote. In those states, the gap grew from 18 to 23 points; in states with mostly in-person or hybrid schools, it grew only from 19 to 21 points, a difference that is not statistically significant. Similarly, a survey in May and June of last year found that a quarter of women (and an eighth of men) who lost their jobs cited child care as the reason. And the economist Ernie Tedeschi estimated last year that about a million and a half mothers had left work because of school closures.

On to another backward-looking question: Were different types of families affected differently?

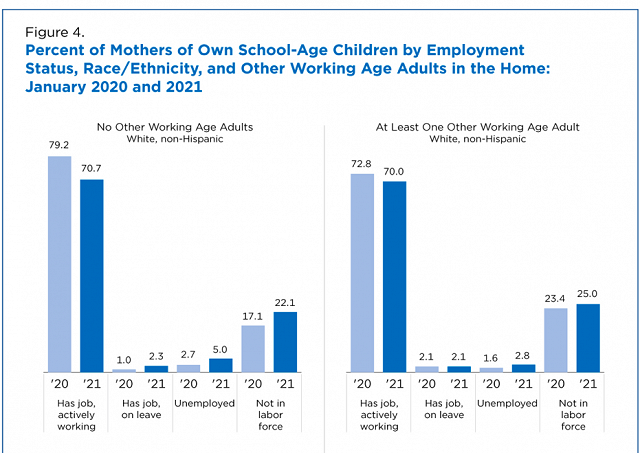

The new census analysis sheds some light on this as well, calculating what happened to moms living with another working-age adult (such as a spouse or cohabiting partner) as opposed to moms without such help at home. Between January 2020 and January 2021, moms living with other working-age adults actually suffered much less damage to their employment. Among white moms, for example, the share actively working fell from 79% to 71 for moms without other working-age adults around, but only from 73% to 70% for moms with spouses or other adults present. The difference is similarly striking for other racial groups.

The researchers don’t offer an explanation for this phenomenon, though it likely stems in part from the class differences between married and single moms. Married moms tend to be more educated, and thus to work in jobs that can be done from home.

All of these patterns say interesting things about the structure of American society and the choices that mothers and fathers make. But they also lay the groundwork for a different future than we’d have seen without COVID-19. Moms’ and dads’ employment may be recovering similarly at the moment, but the acute shock to moms’ work last year could have lingering effects.

The aforementioned NBER paper discusses several possibilities. For example, time out of a job can set a person’s career back; by one estimate, about 13% of the entire gender wage gap is explained by spells out of employment for women. COVID-19 added just such a spell for many women who wanted to be working last year. The pandemic also gave employers a crash course in remote work. If companies remain open to these arrangements in the future, moms could find it easier to get flexible jobs, though such jobs might be seen as stigmatized. COVID-19 could also accelerate automation, since the types of jobs that shed workers this past year are disproportionately easy to automate—in addition to being disproportionately held by women.

In a lot of ways, we’re finally inching back to normal. But this virus won’t be completely done wrecking our plans in all kinds of subtle ways for a long time yet. And in households across America, couples will likely always be navigating the difficult issues of who works and who takes care of the kids, carrying with them the scars and lessons of COVID-19.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.