Highlights

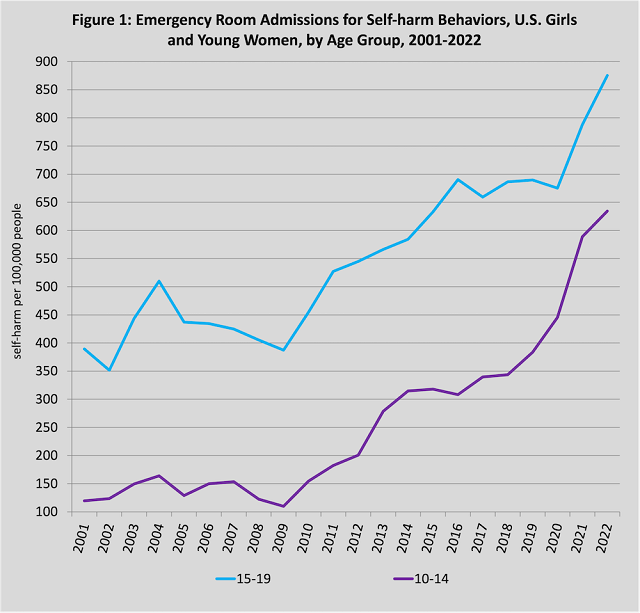

- Five times more 10- to 14-year-old girls were admitted to the ER for self-harm in 2022 than in 2009 (see Figure 1) Post This

- The U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, is now calling for a warning label on social media about adolescent mental health. Post This

- We know what became more popular over this time period, and what has a larger link to well-being among younger teens, especially girls: Social media. Post This

Much of the evidence for the adolescent mental health crisis is based on surveys where teens are asked about their symptoms. Those surveys are anonymous and often ask about symptoms many people many not even realize are indicators of depression. Still, having behavioral evidence of mental health issues is also important, to rule out the possibility that teens are just more willing to admit to symptoms than they used to be. No proof of any rapid change in de-stigmatization of mental health issues has ever been offered, but the argument continues to be made.

One such behavior linked to mental health issues is self-harm, such as cutting or taking too many pills. Some self-harm behaviors are suicide attempts, but others are not (as when a depressed or anxious person cuts themselves as a way of dealing with mental pain). Either way, these are extremely concerning manifestations of mental health issues.

Self-harm is much more common among girls than among boys, so we’ll focus on girls. The CDC keeps data on emergency room admissions for intentional self-harm, and the 2022 data were just released.

The news is not good. ER admissions for self-harm have continued to increase among American girls. Since 2009, more than twice as many 15- to 19-year-old girls and young women have been admitted to the ER for self-harm behaviors in the U.S. Even more shocking, five times more 10- to 14-year-old girls were admitted to the ER for self-harm in 2022 than in 2009 (see Figure 1). That’s 5 times more families taking their 4th to 9th grade daughters to the hospital because they have intentionally harmed themselves.

Source: WISQARS database, CDC

These increases began in the early 2010s, 10 years before the COVID-19 pandemic. And if pandemic lockdowns were causing more girls to harm themselves, why would self-harm increase between 2020 and 2022 when schools and public places were opening back up? Yet ER admissions for self-harm increased 30% among 15- to 19-year-olds and 42% among 10- to 14-year-olds between 2020 and 2022. If the pandemic increased self-harm, 2022 should have been the cure. But instead of going down, self-harm continued to increase.

These data should also be the final nail in the coffin for the theory that a change in hospital coding in 2015 is the cause of the increase. If that were the case, there should be a sudden increase in self-harm admissions between 2015 and 2016, but there is not. Instead, there are increases both before and after 2015. Between 2016 and 2022, when there were no coding changes, ER admissions for self-harm increased 27% among 15- to 19-year-olds and 105% among 10- to 14-year-olds. In other words, recorded self-harm behaviors doubled among 4th to 9th grade girls over a time when hospital coding was the same.

Yet we know what became more and more popular over this time period, and what has a larger link to well-being among younger teens compared to older ones, especially girls: Social media.

The U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, is now calling for a warning label on social media about adolescent mental health. As he cogently argues, you don’t wait for perfect data during an emergency – you act. We’ve already waited nearly a decade since the data clearly showed an increase in depression and self-harm among U.S. adolescents.

This data on self-harm through 2022 is just the latest evidence that we need to act now. With the average teen spending nearly 5 hours a day on social media, there’s plenty of room for change.

Jean Twenge is the author of iGen (2017) and Generations (2023) and professor of psychology at San Diego State University.

Editor's Note: This article appeared first in the author's newsletter. It has been reprinted here with permission.