Highlights

- A new research brief from the National Marriage Project and The Wheatley Institution finds categorical differences between marriage and cohabitation on three relationship health factors: satisfaction, commitment, and stability. Post This

- Despite common myths about cohabitation, when it comes to the relationship quality measures that count—like commitment, satisfaction, and stability—marriage is still the best choice for a strong and stable union, per new research. Post This

After 10 years of on-and-off again dating and eventually moving in together, celebrity couple Liam Hemsworth and Miley Cyrus recently tied the knot in a small ceremony in their home surrounded by family and a few friends. In an interview, Hemsworth talked about the couple’s decision to wed and what it feels like to be a married man, which he described as the “same but different,” adding:

We’ve been together for a long time and it felt like it was the right time to do it…Not much about the relationship changes [after marriage], but you kind of have…the husband and wife thing, it’s great. I’m loving it.

Hemsworth and Cyrus are following an increasingly popular romantic path for young adults today: date, cohabit awhile, then (maybe) get married. The Census Bureau reports that the percentage of cohabiting adults ages 25 to 34 increased—from 12% a decade ago to 15% in 2018, while the percentage of 25-to-34-year-olds who are married continues to decline. Whereas 59% of 25 to 34-year-olds were married in 1978, only 30% are married today. As IFS senior fellow Scott Stanley reported on this blog, cohabitation is now “normative”: the vast majority (67%) of currently-married adults report that they cohabited with either their current partner or another partner prior to getting married.

Not surprisingly, cohabiting is now accepted by most Americans as either a step toward marriage or the equivalent of it. And three-fourths agree that raising kids in a cohabiting relationship is acceptable. In fact, “shotgun cohabitations” are quickly overtaking “shotgun marriages,” and the majority of unmarried births today are to a cohabiting couple, not a lone mother.

So, in a world where most people are shacking up, one might assume that the relationship quality gap between cohabitation and marriage is closing—that, as Hemsworth put it, there is not much of a difference between a committed cohabiting relationship and a married one. This is a prevailing theory among some experts, too, who suggested that as cohabiting became more prevalent and accepted in the U.S., it would begin to look more like marriage. However, research continues to confirm key differences between cohabiting and married relationships—including new research released today from the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and The Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University. This research brief is based on an analysis of the December 2018 YouGov “iFidelity Survey” of 2,000 American adults, which found categorical differences between marriage and cohabitation on three relationship health factors.

As the figure below shows, married individuals were 12 percentage points more likely to report being in the high relationship satisfaction group, 26 percentage points more likely to report being in the highest stability group, and 15 percentage points more likely to report being in the highest commitment group. These findings confirm previous research showing that cohabiting relationships have lower levels of commitment, higher rates of infidelity and conflict, and are significantly more likely to end than married relationships.

Notes: Unadjusted frequency count. Differences tested using simple binomial logistic regression.

Here are three key findings from the NMP/Wheatley Institution analysis that highlight the differences between cohabitation and marriage when it comes to relationship quality:

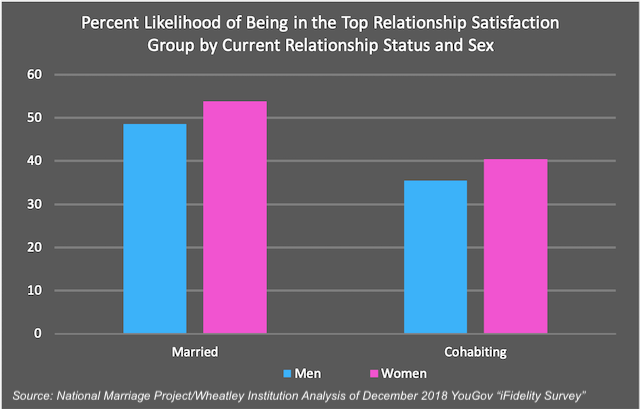

1. Married adults are more likely than cohabiting adults to report relationship satisfaction. In the survey, married adults were more likely to report being “very happy” in their relationship, even after controlling for education, relationship duration, and age.1 In fact, after adjusting for these variables, the married women had a 54% likelihood of being in the highest relationship satisfaction group and married men had a 49% likelihood. For cohabiting women and men, those likelihoods were 40% and 35%, respectively. These group disparities are statistically different.

Notes: Logistic regression model with education, relationship duration, and age controlled.

Assumptions for the predicted likelihoods are someone who has earned an associated degree

or had some college, a relationship duration of 5 years, and an age of 32. The p-value for differences

between married and cohabiting were statistically significant at p < .05 or lower.

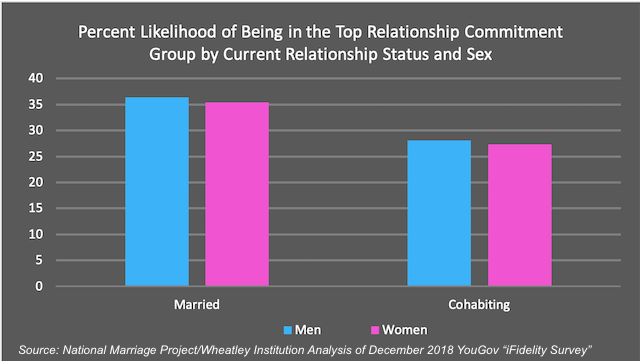

2. Married adults are also more likely to report higher levels of relationship commitment than cohabiting adults. Overall, 46% of married adults were in the top relationship commitment group, compared to slightly over 30% of cohabiting adults (commitment was defined using three items that measured the extent to which individuals valued their relationship and wanted it to continue). Figure 3 below shows that even after adjusting for different life circumstances, married women and men were more likely to report the highest levels of commitment compared to cohabiting individuals. Again, these are statistically significant differences.

Notes: Logistic regression model with education, relationship duration, and age controlled.

Assumptions for the predicted likelihoods are someone who has earned an associated degree

or had some college, a relationship duration of 5 years, and an age of 32. The p-value for

differences between married and cohabiting were statistically significant at p < .05 or lower.

This finding is consistent with other research showing that cohabiting relationships are associated with lower levels of commitment than married relationships. This makes sense when we consider some of the top reasons people give for moving in together, such as convenience, financial benefits, or to “test a relationship.” These are very different from the reasons most people get married. Furthermore, research by Scott Stanley and Galena Rhoades has shown that cohabitating tends to change how people view marriage. As Rhoades explained, “by living together already, both parties have likely developed a thought pattern of ‘what if this doesn't work out,’ thinking you could just move out and move on, which can undermine that sense of commitment that is essential to a thriving marriage, and that most women seeking marriage want.”

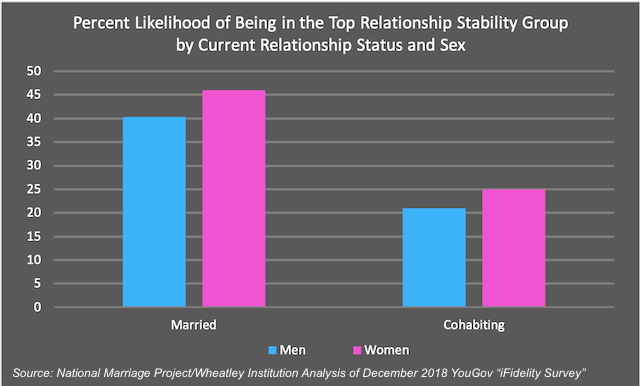

3. Finally, married adults are more likely than cohabiting adults to report higher levels of relationship stability. Overall, 54% of married adults in the survey were in the top perceived relationship stability group, vs. 28% of cohabiting adults (this top category was defined as how likely respondents were to say they thought their relationship would continue). Figure 4 shows the differences after adjusting for age, education, and relationship duration. The differences that remain are statistically significant.

Notes: Logistic regression model with education, relationship duration, and age controlled.

Assumptions for the predicted likelihoods are someone who has earned an associated degree

or had some college, a relationship duration of 5 years, and an age of 32. The p-value for

differences between married and cohabiting were statistically significant at p < .05 or lower.

Indeed, cohabitating relationships are significantly more likely to break up than married relationships, including cohabiting unions that include children, and this holds true even in places, like Europe, where cohabitation has been an accepted practice a lot longer. The 2017 World Family Map found that married couples still enjoy a “stability premium” even in countries like Norway and France.

As cohabiting becomes more commonplace in our society, the lines between getting married and just moving in together can begin to blur, making it harder for young people to recognize what is so special about the marriage vow. But despite prevailing myths about cohabitation being similar to marriage, when it comes to the relationship quality measures that count—like commitment, satisfaction, and stability—research continues to show that marriage is still the best choice for a strong and stable union.

W. Bradford Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Jeffrey Dew is an Associate Professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University and a National Marriage Project fellow, and Alysse ElHage is editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog.

1. We initially also controlled for household income and race/ethnicity. Neither variable was associated with the relationship outcomes. Further, they did not change the association between relationship status and the outcomes, so we dropped them from the models