Highlights

In the high-stakes chess game that is the partisan debate on the family, liberals typically counter conservative concerns over the rise of nonmarital births by urging increased access to contraception and abortion. “The birthrate for unmarried women is up 80 percent since 1980,” the New York Times columnist Nick Kristof wrote in reply to a recent flurry of articles on the subject. Our first response should be to “expand family planning” especially since “after inflation, America’s investment in Title X family planning has fallen some 70 percent since 1980.”

If reason alone ruled in these matters, Kristof’s point would be more compelling than it is. After all, most nonmarital births are unintended. Mothers who get pregnant unintentionally are more likely to delay prenatal care, to smoke and drink during their pregnancy, and to give birth to low weight babies. Unintended pregnancy rates are far higher among poor and low-income single women who would, presumably, benefit from help procuring more expensive long-acting contraception and safe abortions.

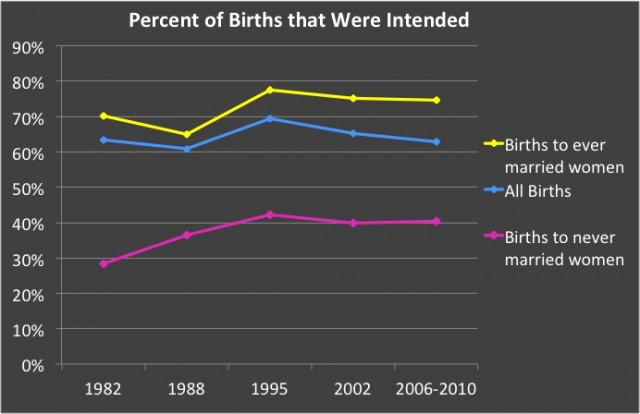

In this case, however, logic needs to wrestle with a number of inconvenient truths. First among them is a fact almost never mentioned in these discussions: over the past 30 years both married and unmarried women have become significantly more likely to plan their births. In the years between 1982 and 1995, intended births increased significantly during and after the time, as Kristof might observe, Title X funding suffered deep cuts. The chart below tells the story.

Source: National Vital Statistics Birth Data Files

In 1982, about 70% of births among married or previously married women were intentional. After a brief detour southward, that number rose to a little over 77% by the mid-90s. More striking were the trends among unmarried women. In 1982, 28.4% of their births were intended. By 1995? Over 40%, where the number remains, more or less, today. This happened even as unmarried women were getting fewer abortions. According to the CDC, in 1980 only 33% of pregnancies in this group resulted in a live birth, compared to 47% in 1995 and approximately 54% in 2009. In sum, more unmarried women who are having children today are doing so because they want to.

More unmarried women who are having children today are doing so because they want to.

The role played in these particular trends by public funding for contraception is at best ambiguous. Title X monies did decline during the Reagan years, but by the mid-1990s Medicaid money specifically for family planning was more than picking up the slack. As of 2010, overall public spending on family planning was 31% higher than it was in 1980, with the bulk of the rise occurring after 1994—almost precisely the moment when the increase in intentional births stalled.

That’s not to say that a cut in funding would have no impact. This study by Melissa Kearney and Phillip Levine found that expanding Medicaid family planning decreased births up to 9% among women over 20 who were newly eligible for Medicaid-funded family planning (the study does not distinguish between married and unmarried participants, nor does it probe intentionality). Another program, this one in St. Louis, Missouri, providing women with free access to long-acting reversible contraceptives like implants and IUD’s also reduced rates of unintended childbearing for at least three years, though the study can’t tell us anything about the intentions subjects bring to later pregnancies once the IUD is removed. Nor should the lack of a relationship between trends in intentional births on the one hand, and public contraceptive funding on the other, call into question the fact that the majority of unmarried women who give birth didn’t plan to do so, and, further, that abortion rates among this group are almost five times as high as among married women.

Earlier scholars assumed that “unintended” was synonymous with “unwanted.” They no longer believe that to be the case.

But the under-reported increase in intended births among unmarried women reinforces the nuanced conclusions researchers have been reaching about the complex psychology of pregnancy and childbearing. Earlier scholars assumed that “unintended” was synonymous with “unwanted.” They no longer believe that to be the case. A wide variety of studies have found that most unintended pregnancies are actually “mistimed,” that is, a mother-to-be was hoping to get pregnant but not at the particular moment that she did. (Eleven percent of all pregnancies, and a higher proportion among teenagers and women over 35 with children, are described as unwanted.) “Pregnancy intendedness is complex and difficult to measure,” observe the authors of one study on the topic. “Previous research has shown that the concept may not be meaningful to some women or that women may be ambivalent.” Experts have long been puzzled by the very inconsistent and even negligent use of contraception by young women; this helps explain why.

More importantly, the 40% of single mothers who say they planned their pregnancy helps to clarify a stubborn misunderstanding about the decline of marriage in the United States. Liberals presume structural forces—poverty, a dearth of marriageable men, and limited access to contraception and abortion—explain the rise in unmarried childbearing of the past half-century. These factors matter, but only up to a point. There’s no way to understand what’s happened to the family without looking at cultural changes as well. A growing number of Americans view having a child and getting married as two entirely unrelated life choices. We shouldn’t be surprised to find that people actually act on their beliefs.