Highlights

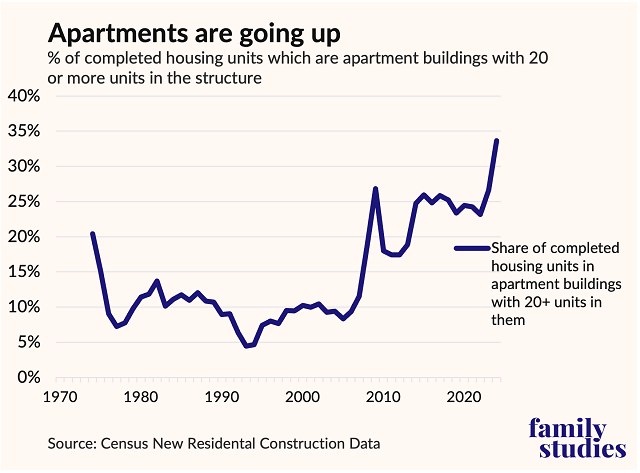

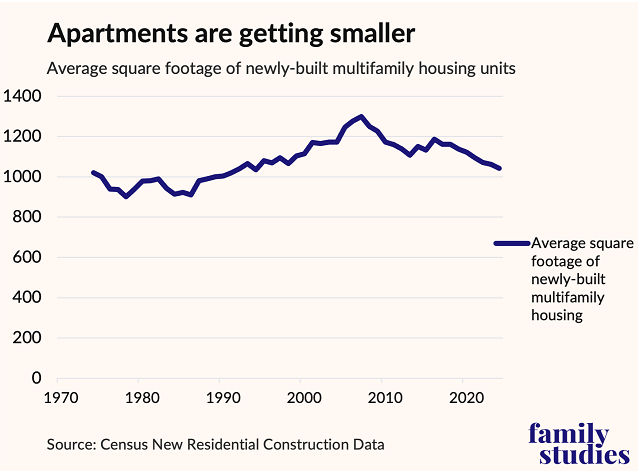

- A new IFS brief shows that while there has been a massive boom in apartment construction, apartments are getting smaller with fewer bedrooms. Post This

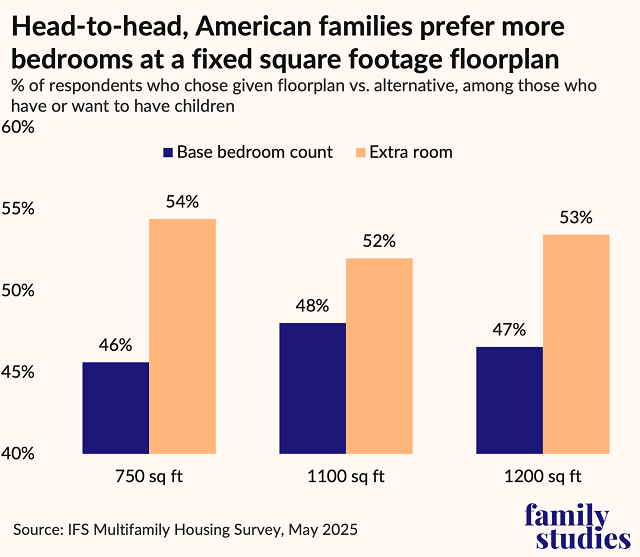

- Across all apartment sizes, Americans who want families chose units divided into additional bedrooms. Post This

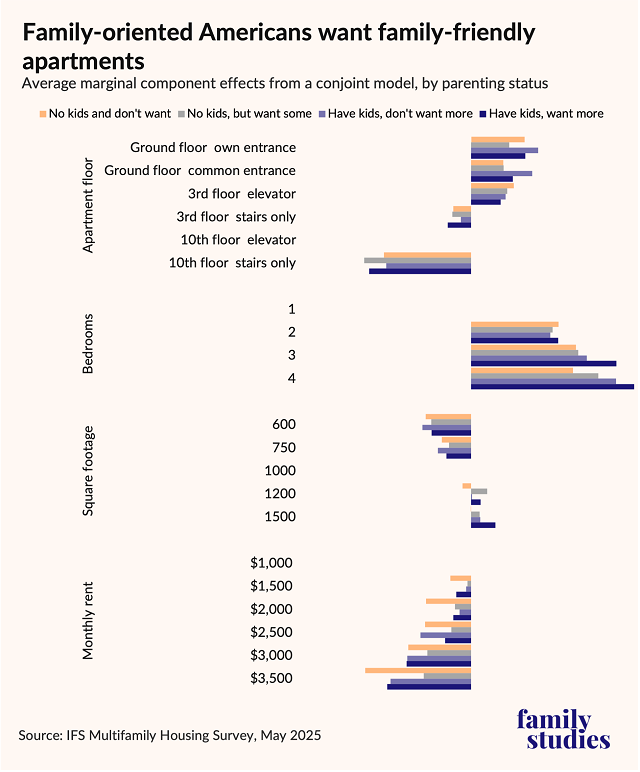

- In a conjoint survey design, we found that bedroom count was more influential on the willingness to have another child than almost any other apartment trait, especially for those who want more kids. Post This

- Family-friendly units have lower vacancy rates, longer tenures, and lower nonpayment risks. Investors willing to finance family-friendly construction are likely to get better returns. Post This

Talk to any young couple considering having a child and one thing is almost certain to come up: the housing situation. Family-suitable housing is increasingly out of reach for young American families, and fertility is suffering as a result. In prior research, we laid out this affordability problem. But there’s a second problem facing many families: not only are the “starter homes” they would prefer either unaffordable or unavailable, but there aren’t even rentable apartments suitable for a baby, either.

As we show in our new brief on family-friendly apartments, there has been a massive boom in apartment construction, yet apartments are getting smaller with fewer bedrooms.

This is a serious problem for young families. Although most Americans want to raise a family in a single-family house, many would be willing to have a first child or even a second in an apartment—if they had extra bedrooms.

In a conjoint survey design where we asked almost 6,000 U.S. respondents to “trade off” different apartment traits, we found that bedroom count was more influential on their willingness to have another child than almost any other trait, especially for Americans who want more kids.

We also found a lot of other evidence that family-friendly apartments are in high demand: apartments with more bedrooms have lower vacancy rates, lower turnover rates, and are likelier to be purchased for luxury and vacation usage. But just to validate this, we also did randomized experiments where we showed respondents realistic floorplans of apartments with identical square footage but different bedroom counts. Across all apartment sizes, Americans who want families chose units divided into additional bedrooms.

In other words, Americans prefer apartments that apartment builders aren’t building.

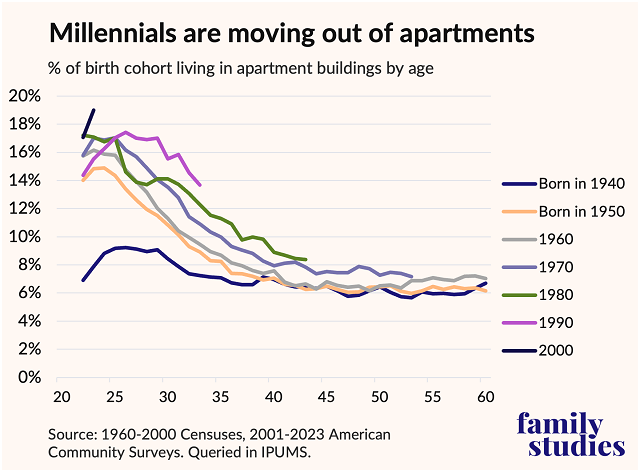

This is a market failure. The reasons for this failure are many. Part of it seems to be a simple failure by property investors and developers to read the market. The huge Millennial cohort needed apartments, so developers built more apartments—but the Gen Z cohort is much smaller, and the next cohort will be smaller still. Moreover, that big Millennial cohort, born around 1990, is now aging into years where apartment demand is lower.

Beyond this, many property developers are extremely cautious: hesitant to take on smaller developments where family-friendly floorplans could be tested out, wary to adopt floorplans that haven’t shown viability in dozens of other markets, and very conservative in assumptions about market returns on investment. Most property developers we spoke to tend to assume that studio apartments and 3-bedroom apartments will have similar turnover, similar vacancy rates, and similar nonpayment risks. But family-friendly units actually have lower vacancy rates, longer tenures, and lower nonpayment risks. Investors willing to finance family-friendly construction are likely to get better returns.

But beyond frictions in private real estate investment, there are government issues, too. In some areas of the country, builders must provide parking spots per bedroom, which discourages multi-bedroom floorplans. Those rules should be replaced with parking rules per unit. Moreover, many jurisdictions impose height limits on apartment buildings—this makes no sense. If an apartment building is going to be built, it makes more sense to make it as tall as is possible, and thus limit the amount of land taken up by apartments and taken away from more generally family-friendly units. Many jurisdictions also prohibit “single stair” layouts of a certain height, making smaller, cheaper, more family-friendly layouts on building corners impractical. Slow permitting processes exacerbate these issues.

Finally, to top it all off, many government programs subsidize apartment construction—but do so per unit rather than per bedroom. Public housing trust funds are often mandated to produce a certain number of public housing units, not bedrooms, and so poor families with children have few options. Likewise, the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit is given to developers based on the number of units rented to poor people rather than bedrooms. A huge share of impoverished Americans are children—yet low-income housing disproportionately subsidizes housing for low-income singles. Policymakers could easily address this problem.

In our new brief, we lay out this evidence of demand for multifamily apartments, the reasons they are underprovided, and more. Check it out for more details.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.