Highlights

- The other factor driving young people away from marriage is their growing dependence on their parents. Post This

- Parents today often shield their children from the responsibilities of young adulthood for much longer than previous generations. Post This

- Today’s youth are shielded for too long from important responsibilities they need to mature, and, as a result, fail to develop the skills and capacities necessary to flourish. Post This

In the early 2000s, when a team of researchers at UCLA entered the homes of 32 two-parent families in the greater Los Angeles area to study the family dynamics of middle-class households, one consistent pattern of behavior struck them: household children were highly dependent on their parents, even into their teen years. Stories ranged from parents helping their school-age children “carry out basic self-care tasks such as brushing hair...and picking up belongings” to more egregious examples, such as an 18-year-old son forcing his father to untie his shoe.

These children have since aged into adulthood, and, according to many experts, now make up the most individualistic generation on record. Today’s 20-somethings are typically branded as independent explorers, wary of commitment, who place a high value on personal freedoms and autonomy. These individualistic attitudes are especially apparent in young peoples’ decisions to delay or forgo family life; indeed, scholars often cite young Americans’ individualism as a catalyst for reduced marriage and fertility rates. After all, if marriage and childrearing are fundamentally predicated on self-sacrifice and lifelong commitment, who could expect today’s young free-spirited souls to settle down and start a family?

This view—that 20-somethings’ decisions to delay or forgo marriage are a consequence of unwavering individualism—only tells part of the story. The other factor driving young people (of which I am one) away from marriage is their growing dependence on their parents. Parents today often shield their children from the responsibilities of young adulthood for much longer than previous generations. Consequently, today’s young adults are less willing or able to take on responsibilities characteristic of their age and necessary for building a family. Because of this prolonged sheltering, many young adults view the most significant and consequential responsibilities of adulthood—marriage and childrearing—as concerns for a distant future self, not the present. Paradoxically, the way to make marriage more appealing to younger Americans may be to promote more independence, not less.

But first, it is important to note just how much family life has declined among young Americans. From 1970 to 2018, the median age at first marriage climbed from 21 to 28 for women and 23 to 30 for men. Over the same period, the percentage of American adults (age 25-50) who never married climbed from 9% to 35 percent. The same trends emerge when it comes to childbearing. Since 1970, the total fertility rate has declined from 2.5 births per woman to about 1.7 births per woman. The declines are highly concentrated among those in their 20s; even since 1990, fertility rates among women in their early-20s (20-24) and late-20s (25-29) have fallen by 73% and 43%, respectively.

To be sure, these data appear to support the conventional wisdom: Today’s 20-somethings are spending the first decade of their adulthood exploring, pursuing their own ends, and living out an individualistic ethos. However, other data suggest that young Americans’ unbridled individualism does not entail independence. In other words, even though young people appear pre-occupied with their own pursuits, they are not going it alone—they are increasingly reliant on their parents. In fact, young peoples’ collective choice to delay family life appears to be a product of prolonged dependence rather than independence.

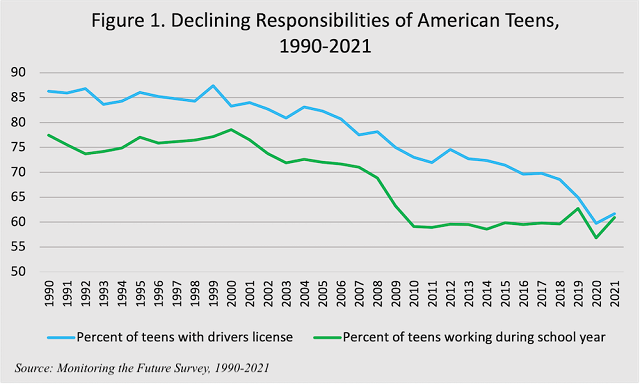

Psychologist Jean Twenge was the first to document how contemporary teens are much slower to take on the responsibilities of young adulthood in her now-seminal iGen. According to Twenge, when it comes to hitting the developmental milestones of young adulthood, “18-year-olds now look like 14-year-olds.” And the data bear this out. Figure 1 shows the percentage of high-school seniors who work a part-time job during the school year and the percentage who have their driver’s license—both of which are rites of passage into young adulthood.

From 1990 to 2021, the percentage of high school seniors who worked a job during the school year declined from 77% to 61%, and the percentage of high school seniors who have their driver’s licenses declined from 86% to 62 percent. Interestingly, there was very little difference between sexes—both male and female 12th graders were about equally as likely to get their driver’s license and work during the school year. While some may say that today’s teens are taking on larger, more significant responsibilities compared to previous generations—such as additional schoolwork or extracurricular activities—this is not true. Compared to previous generations, today’s teens spend about the same amount of time on homework and are less likely to participate in a variety of extracurricular activities.

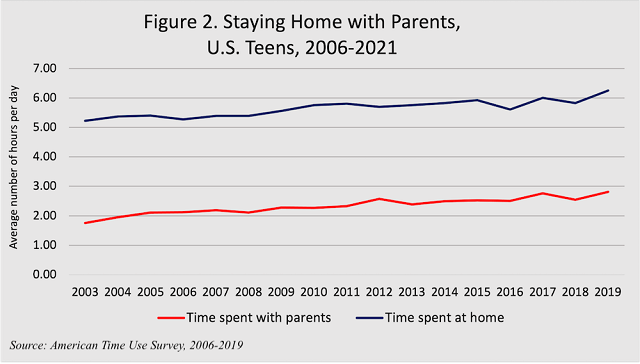

The two indicators above—working a job and getting a driver’s license—are perhaps the two greatest sources of independence available to young adults. When you are able to drive a car and earn your own money, gone are the days of relying on your parents for an allowance or a ride. That these two indicators are in such stark decline suggests that today’s young adults are far more dependent than they once were. Breaking from the constant supervision of one’s parents was once assumed to be a near-universal desire of American teens; today, young people seem much more content relying on mom and dad. However, as Figure 2 indicates, today’s teens may not even need to ask for a car ride or allowance, because they are opting to spend much more time at home with their parents.

Figure 2 displays the average number of hours that American teens (age 15-19) spend with their parents and at home. Even before the pandemic forced teens into close quarters with their parents, teens’ time with their parents and their time at home climbed by over an hour since 2006. On the average day in 2019, American teens spent over 6 hours per day at home, and nearly 3 hours per day with their parents. Although time spent at home is virtually the same among males and females, girls appear to be driving the large increases in time with parents. Compared to 2006, teen girls now spend an hour more with their parents per day, whereas boys only spend 30 more minutes. Much like trends in southern Europe, in which young people are spending more time with their parents and delaying marriage, young Americans appear to be more hesitant to leave their parents’ nest.

It is not as if these teens are being held captive by helicopter parents—they seem to prefer staying home. According to the Monitoring the Future survey, a declining share of high school seniors reported being eager to leave home and live independently of their parents. In 1990, over one-third (34%) of 12th graders “strongly agreed” that they were eager to leave home, but by 2021, the share of teens eager to leave home fell to only 22 percent.

It is insignificant whether these trends are due to excessive protectionism (“you can’t play outside, it’s too dangerous”) or inadequate encouragement (“I don’t care if you play outside or play video games, just don’t bother me”) from parents. In either case, the results are the same: Today’s youth are shielded for too long from important responsibilities they need to mature, and, as a result, fail to develop the skills and capacities necessary to flourish as young adults. Because today’s teens are not conditioned to take on adulthood, the prospect of confronting the most significant responsibilities of adulthood—such as a lifelong commitment to love another person—may feel particularly weighty and out of reach.

So, when young people say they are holding off on getting married until they figure their own lives out, we should trust them. They likely have not had the opportunity to develop the skills and capacities to handle adulthood’s basic tasks, never mind the most important ones. To make marriage and childrearing more attainable for young adults, parents must allow (or encourage) their children to take on the responsibilities of young adulthood. For marriage and family life to prosper, young people must become more independent, not less.

Thomas O’Rourke is a policy researcher and writer who studies social capital, economic mobility, and anti-poverty policy.