Highlights

- In 2022, 6.7 million U.S. children ages 7 to 17 years old, or 15% of all children that age, received treatment or counseling from a mental health professional. Post This

- Children and adolescents in single-parent and stepfamilies were more likely than those living with married birth parents to be taking psychiatric medications for emotional, attention, or behavioral conditions. Post This

- Strategies for dealing with negative factors in the child’s family environment and genetic heritage should be part of any mental health treatment plan for children. Post This

The topic of children’s mental health received a great deal of attention during and following the COVID pandemic. In 2023, the Surgeon General of the U.S. issued an advisory on the apparent upsurge in youth mental health problems, calling it the “crisis of our time.”1 But amid the many reports issued by professional associations and federal and state agencies, a curious lack of attention has been paid to the roles that family dynamics play in creating or ameliorating stress for children. Nor has there been much mention of the part that families play in seeking out and working with professional psychological help when their offspring need it.

One of the major federal population surveys on children’s health issues, the National Survey on Children’s Health (NSCH) provides periodic information on both the health services that young people get, as well as on key characteristics of the different types of families in which they live.2 What follows is my examination, using these data, of how a child’s family structure relates to his or her need for and receipt of mental health services. Download the full research brief here.

8 Million School-aged Children Get or Need Psychiatric Care Each Year

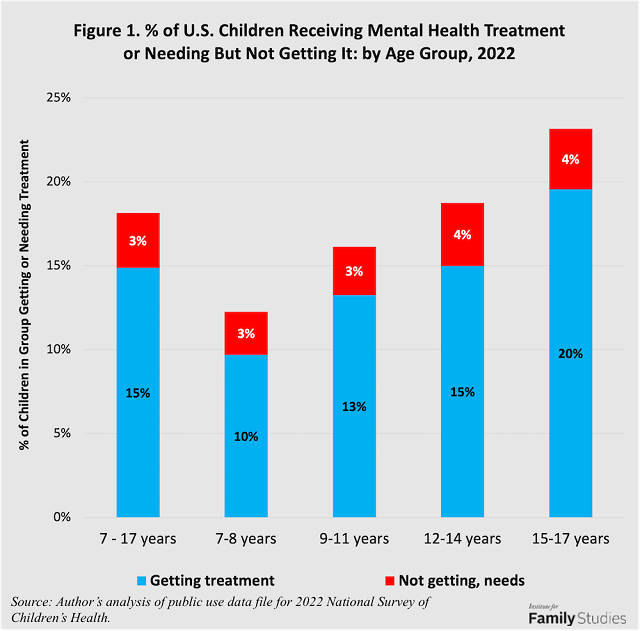

In 2022, 6.7 million U.S. children ages 7 to 17 years old, or 15% of all children that age, received treatment or counseling from a mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychiatric nurse, or clinical social worker. They received this care for a variety of problems and conditions, including anxiety, depression, behavioral or conduct problems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism. An additional 1.3 million, or 3%, needed to see such a person, according to their parents, but did not do so. Thus, of the total 8 million children who needed psychiatric attention, 82% received it, while 18% did not.3

As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of youngsters getting mental health treatment doubles with age, from 10% of 7- and 8-year-olds to 20% of 15 to 17-year-olds. The proportion needing but not getting care increases from 3% of the younger elementary-school-agers to 4% of the older high-schoolers. One in eight children in the early elementary grades and one in four adolescents in the last three years of high school were either receiving or needing psychological counseling in 2022.

4.6 Million Taking Psychoactive Drugs

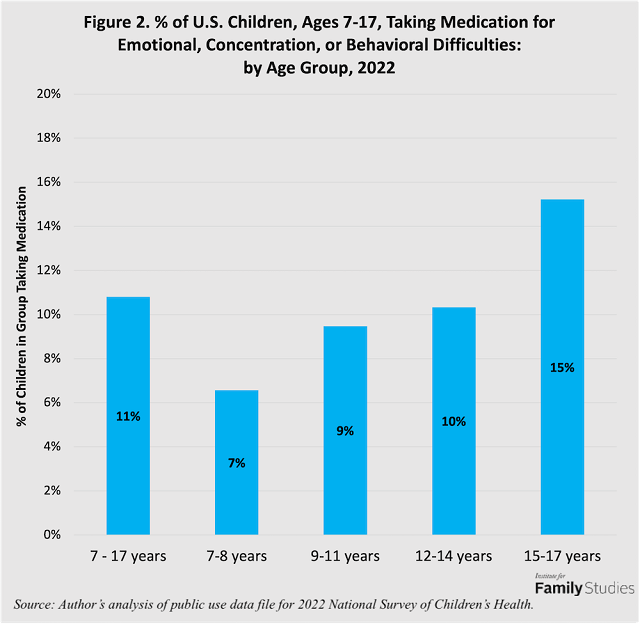

As a consequence of receiving mental health counseling or treatment, parents are often given a prescription for medication that the child or adolescent is told to take regularly. Commonly prescribed drugs for young people include Adderall and Ritalin4 for ADHD and conduct disorders; Prozac and Zoloft5 for depression and anxiety problems; and Abilify and Risperdal6 for autism. In 2022, 11% of children ages 7 to 17 were taking medication because of difficulties with their emotions, concentration, or behavior. The proportion of youngsters taking such drugs more than doubled with age, from 7% among 7- and 8-year-olds to 15% among 15 to 17-year-olds. One in 15 children in the early elementary grades and one in seven adolescents in the last three years of high school were taking psychiatric drugs regularly.

Girls More Likely Than Boys to Get Mental Health Care, But Reasons Differ

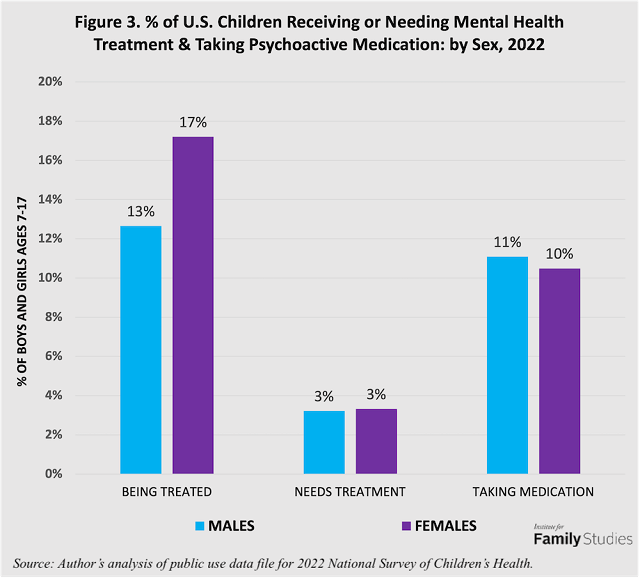

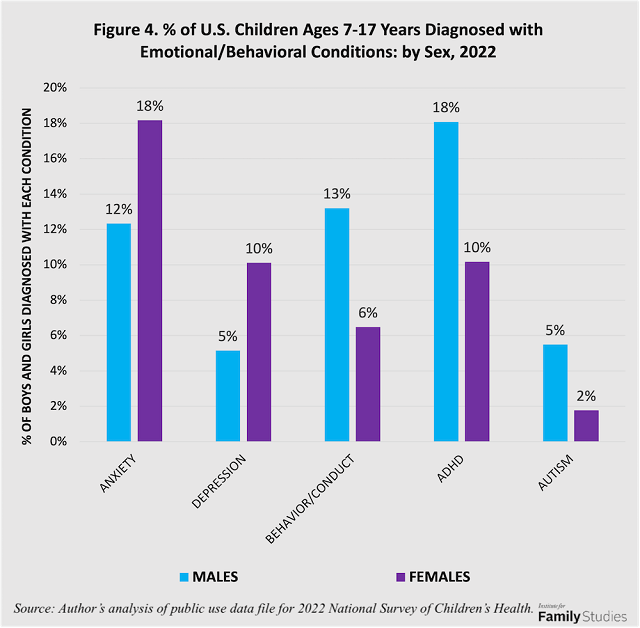

The frequency of receiving mental health treatment differed significantly by sex in 2022, with 13% of boys and 17% of girls receiving care. In addition, 3% of both males and females needed but did not get care. Boys and girls were equally likely to be taking psychoactive drugs: 11% of each sex.

The conditions for which boys and girls were being treated also differed. Girls were twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression (5% versus 10%) and 1½ times more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety problems (12% versus 18%). Boys were twice as likely to be diagnosed with ADHD (18% versus 10%) and conduct disorders (13% versus 7%), and three times more likely to be diagnosed with autism (6% versus 2%).

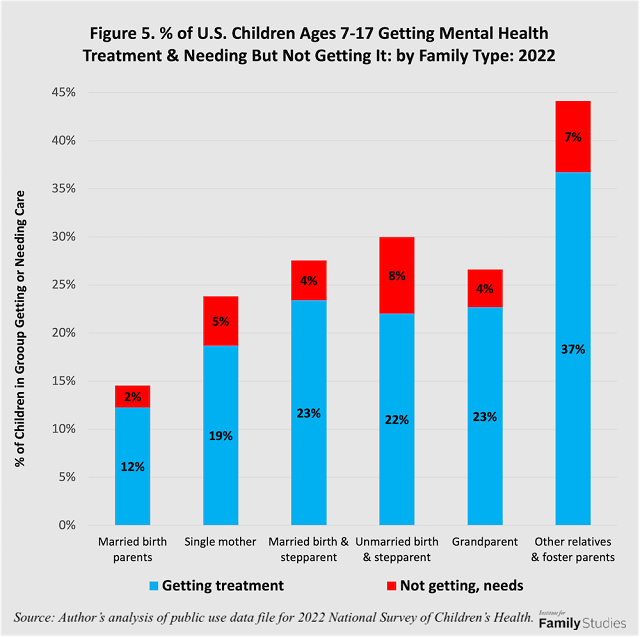

More Kids in Single-Parent & Stepfamilies Being Treated for Mental Health Problems

The frequency of mental health treatment varied greatly across the different types of families in which American children reside. Children who lived with both their married birth parents were least likely to need or receive counseling. Even so, in 2022, 12% were getting therapy and 2% needed but did not receive it.7 Kids living with single mothers due to parents’ marital separation or divorce, or birth to unmarried parents were 1 and 2/3 times more likely to require treatment: 19% were receiving care, and 5% needed care but did not receive it.8

Young people living with a birth parent and a stepparent following a divorce or unmarried birth were also more prone to psychological conditions that required psychiatric treatment than were those living with married birth parents. This was true whether the step couples were married or not: about the same proportion of children (23%) were getting care in each of these family situations. But 4% of the children in married stepfamilies needed professional care but were not getting it, compared to 8% of those in unmarried stepfamilies.

Children and adolescents who lived apart from both parents, such as with grandparents or with other relatives or foster parents, also had elevated rates of receiving or needing mental health treatment. Of those residing with one or both grandparents, 23% were getting care and 4% needed professional care but were not receiving it. Of those with other relatives or in foster care, 37% were getting care and 7% needed it.

Compared to living with married birth parents, where 2% of children needed care but did not get it, the unmet need percentage was significantly higher among children with single moms (5%), in both types of stepparent families (4% and 8%), among children living with a grandparent (4%), and among those living with other relatives or foster parents (7%). In these groups, the ratio of children needing care to the total number getting or needing care ranged from 15% to 27%.

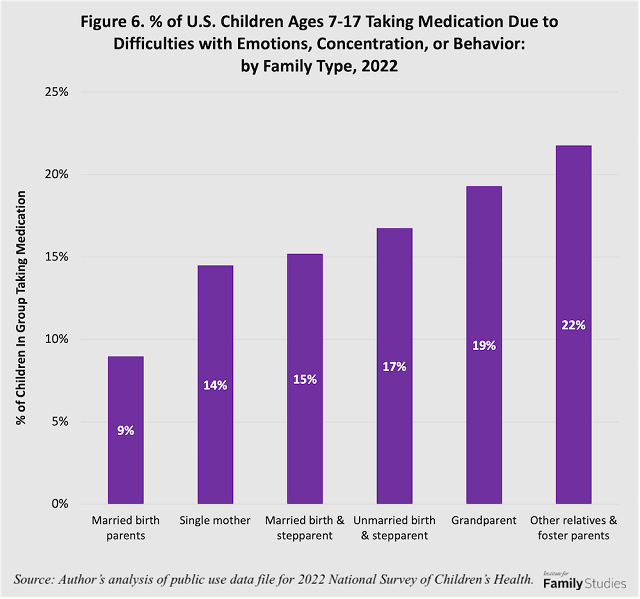

More Children in Single-Parent and Stepfamilies Taking Psychiatric Medication

Children and adolescents in single-parent and stepfamilies were more likely than those living with married birth parents to be taking psychiatric medications for emotional, attention, or behavioral conditions. As shown in Figure 6, 14% percent of youngsters living with their mothers only and 15% of those living in married-birth parent with stepparent households were taking psychiatric drugs. So were 17% of those in unmarried stepfamilies, 19% of children living with grandparents, and 22% of those cared for by other relatives or foster parents. By comparison, 9% of children living with married biological parents were taking such medications.

Taking the Family Into Account

Why are disorders that require mental health treatment more common among young people from disrupted families? Most children experience stress and feel anxiety, sadness, or anger when their parents split up. Many show short-term behavioral disturbances as well.9 But after a period of time, provided their subsequent life conditions are not deprived or chaotic, most are able to adjust and do reasonably well.10 Significant minorities, however, show longer-term maladjustment, such as those who are high-school dropouts or do not complete college, those with chronic joblessness, premature sexual involvement and parenthood, and juvenile delinquency or adult criminality.11 Young persons from disrupted families whose lives go awry usually have other risk factors working against them, such as inadequate parental support and supervision, negative peer influences, and histories of family pathology.12

Compared to children who live with their married birth parents, children living with divorced or never-married mothers, or with a birth parent and a stepparent, are more likely to come from families with histories of drug or alcohol problems, mental illness, or criminal conduct, as I showed in an earlier IFS research brief.13 The presence or absence of such histories of family pathology may help explain why some young people show longer-term ill effects of family disruption, whereas others do not. When parents have such a history, their children may be burdened not only by a less than ideal home environment, but also by a genetic legacy that may incline them toward emotional instability or learning challenges.

The association between family structure and children’s mental health shows the importance of addressing family issues when attempting to ameliorate a young person’s anxiety, depression, or problematic “acting-out” conduct. It is not enough to prescribe a pill.14 Nor is it realistic to expect that low-cost mental health interventions in schools or on social media will give young people the resilience to withstand family disruption, conflict between parents, harassment from classmates, or peer influences that encourage defiant or delinquent conduct.15 Strategies for dealing with negative factors in the child’s family environment and genetic heritage should be part of any mental health treatment plan or program for children and adolescents.

Editor's Note: Download a PDF of this research brief here.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. NASEM Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education.

2.Lebrun-Harris et al (2022). Five-year trends in US children’s health and well-being, 2016-2020.

3. Author’s analysis of public use data from the 2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

4. Adderall is a brand name for a mix of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine. Ritalin is a brand name for methylphenidate.

5. Prozac and Zoloft are brand names for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

6. Abilify and Risperdal are brand names for antipsychotic medications aimed at reducing the irritability and aggressive behavior that may accompany autism.

7. Among children living with cohabiting biological parents, 7% received mental health care and 3% needed but did not get it. These results are not shown in Figure Five as they are discrepant with findings from earlier rounds of the NSCH. In 2019, for example, 17% of this group were receiving mental health treatment and 4% needed but did not receive it. The differences may be due to sampling fluctuations with respect to a relatively small subgroup of the child population.

8. Children living with their fathers only were not significantly different from those with married birth parents: 12% of them were receiving care and 3% needed it. These results are discrepant with findings from earlier rounds of the NSCH. In 2019, for example, 17% of children living with fathers only received mental health treatment and 2% needed but did not get it. Again, the discrepancies may be due to sampling fluctuations with respect to a relatively small subgroup of the child population.

9. Nicholas Zill, “How Family Transitions Affect Students’ Achievement,” Institute for Family Studies, October 29, 2015. And Nicholas Zill & Brad Wilcox, “What Happens at Home Doesn’t Stay There: It Goes to School,” June 8, 2017.

10. Nicholas Zill. “For Getting Kids Through College, Single-Parent Families Are Not All The Same,” May 25, 2020.

11. Paul Amato, “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation,” Future of Children 15, no. 2 (2005): 75-96; Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur, Growing Up With a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1994); Nicholas Zill, “Family Change and Student Achievement: What We Have Learned, What It Means for Schools,” in Family-School Links: How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes?, ed. Alan Booth and Judith F. Dunn (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996). Nicholas Zill & Brad Wilcox, “What Unites Most Graduates of Selective Colleges? An Intact Family,” June 9, 2020.

12. Nicholas Zill, "Substance abuse, mental illness, and crime more common in disrupted families." Institute for Family Studies, March 24, 2015. Also, Zill. "Kids of Single Parents More Likely to Witness Domestic Violence." IFS, January 5, 2015. Also, Zill, "Even in Unsafe Neighborhoods, Kids Are Safer in Married Families," IFS, February 23, 2015.

13. Ibid.

14. Jenny Taitz. The danger of relying on anti-anxiety drugs. Wall Street Journal, Jan. 27, 2024: page C5. Matt Richtel, "More young people are on multiple psychiatric drugs, study finds," The New York Times. Feb. 16, 2024.

15. Darby Saxbe, "This is not the way to help depressed teens." The New York Times, Nov. 26, 2023: Sunday Opinion, page 9.