Highlights

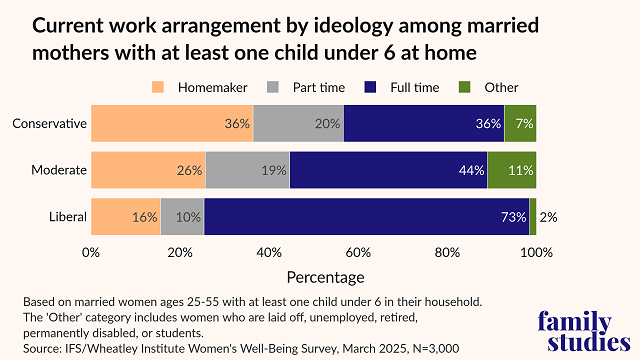

- In reality, 56% of married conservative mothers with young children reported their current work arrangement as either a stay-at-home mother (36%) or part-time (20%). Post This

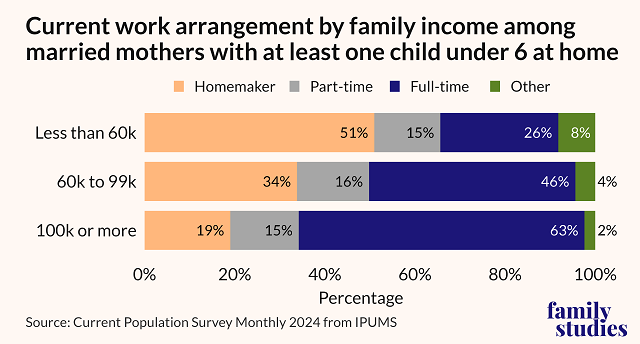

- It’s actually affluent “elite” moms who are the least likely to be stay-at-home mothers. In fact, mothers of young children in the lower two income brackets are approximately twice as likely as their wealthier counterparts to be homemakers. Post This

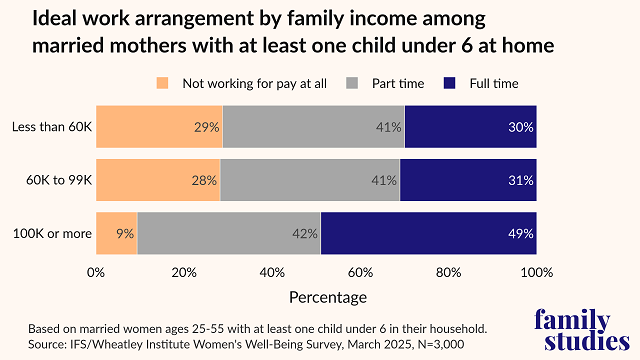

- Married mothers of young children in households earning less than $60,000 and between $60K-90K were significantly more likely than those earning more than $100,000 to report “not working for pay at all” as their ideal, per the 2025 Women’s Well-Being Survey from IFS and the Wheatley Institute. Post This

It’s not liberal but conservative women who are embracing the ‘Supermom’ ideal made popular by second-wave feminism at the end of the last century. This is the woman who can cook, clean, care for her children, and embrace a big career, all without breaking a sweat. The kind of woman celebrated in the 1979 Enjoli perfume ad who sang, “I can bring home the bacon, fry it up in a pan, and never, never, never let you forget you’re a man” as she is depicted first in a peach bathrobe (for cooking), then a blue suit (for working), and then an elegant evening dress (for a night out with her hubby). At least, that’s the clear takeaway of a recent Wall Street Journal article, “The Conservative Women Who Are ‘Having It All.’”

The piece by Pamela Paul spotlighted conservative women who are defying the traditional ideal of stay-at-home motherhood, opting instead for a high-powered career while juggling a rich family life. The Journal painted positive portraits of work-hard, care-well mothers by offering examples of right-leaning women who are pursuing successful and demanding careers in Republican Washington, conservative media and the defense industry.

Paul suggested these women, more than liberal women, are able to “have it all” because they generally have extra “grit,” supportive husbands and a strong faith that makes combining career and family more doable.

The most extraordinary example given was White House aide May Mailman, a Harvard-trained lawyer and mother who is pregnant with her third child. Mailman flies home to Houston on the weekends to relieve her nanny, spend time with her husband and catch up with her two young children. According to Paul, conservative moms like Mailman are more and more common these days with “nearly as many Republican mothers (67%) [working] outside the home as Democratic mothers (70%).”

More women are embracing this “Supermom” model for both cultural and economic reasons, in the Journal’s account. Culturally, more mothers are devoted to a career “whether for their sense of self, their desire to contribute financially or as a way to pursue their passion.” And economically, for “most women,” Paul argued, “whatever their politics, housewifery is a nonstarter; outside a wealthy elite, the two-income household is just economic reality.”

But the economic and ideological reality on the ground for married mothers cuts against the storylines told by the Journal.

Who is Most Likely to be a Stay-at-home Mom?

Economically, federal data and a recent survey conducted by the Institute for Family Studies and the Wheatley Institute show that it is the women from lower-income households—as well as those from middle-income households—who are more likely to be stay-at-home mothers.

Data from the federally funded 2024 Current Population Survey indicates that affluent married mothers with young children and a household income of at least $100,000 were significantly less likely to be homemakers than lower-income families earning less than $60,000 or middle-income families taking home $60,000-$99,000.

Conversely, married moms with young children and a household income of more than $100,000 have a vastly larger likelihood of working full-time than those women with a household income of less than $60,000. Contra the Journal, it’s actually affluent “elite” moms like Mailman who are the least likely to be stay-at-home mothers. In fact, mothers of young children in the lower two income brackets are approximately twice as likely as their wealthier counterparts to be homemakers.

Furthermore, married mothers of young children in households earning less than $60,000 and between $60K-90K were significantly more likely than those earning more than $100,000 to report “not working for pay at all” as their ideal (29% and 28%, respectively), according to the 2025 Women’s Well-Being Survey from the Institute for Family Studies and the Wheatley Institute. For married women with young children in households earning $100,000 or more, only 9% reported “not working for pay” as the ideal, while 49% reported full-time work as the ideal.

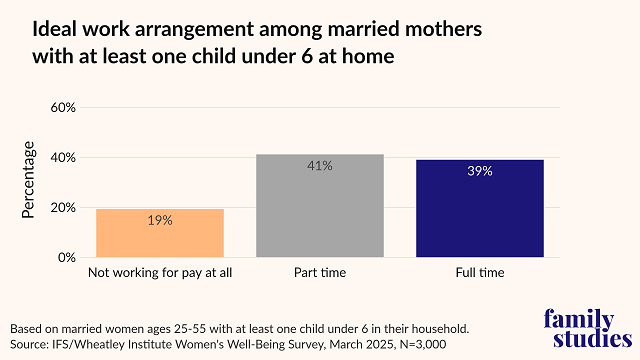

Interestingly, around 41-42% of women in all income categories reported working part-time as the ideal work arrangement. Contrary to Paul’s “have it all” ideal of motherhood, which would seem to correspond to a largely full-time model of work, most married mothers with young children do not wish to combine full-time work with their family responsibilities. The data show that most married mothers would much more prefer a less strenuous work-life balance — either not working for pay at all, or engaging in part-time work.

Are Liberal Women More Likely to Work Full Time?

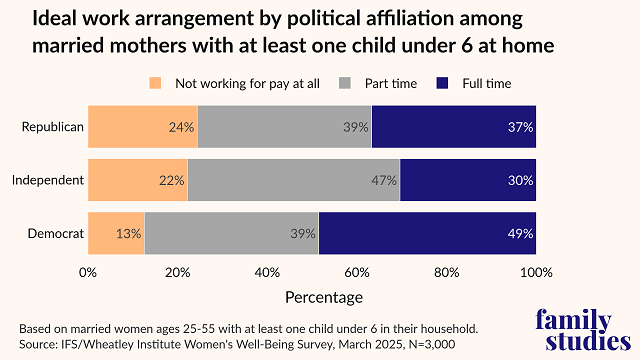

Culturally, the Journal’s account also misses the mark. Both conservative and Republican mothers of young children are less likely to aspire or actually “have it all” — again, if “having it all” is defined as combining full-time work with raising young children.

When looking at ideology, the suggestion that full-time work is the dominant reality for conservative mothers of young children could not be more off the mark. Seventy-three percent of married liberal women with young children report working full-time, compared to 36% of conservative women.

The 37-percentage point difference between full-time working liberal women and conservative women shows that the “mission-driven” lifestyles of high-profile conservative moms spotlighted in the Journal are not the rule, but the exception.

In reality, 56% of married conservative mothers with young children reported their current work arrangement as either a stay-at-home mother (36%) or part-time (20%). By contrast, only 16% of liberal mothers reported being a stay-at-home mom and just 10% as working part-time. What’s more, as the Women’s Well-Being Survey shows, this split is similar in comparing Democratic and Republican married mothers of young children: only a minority of the latter work full-time, compared to a majority of the former.

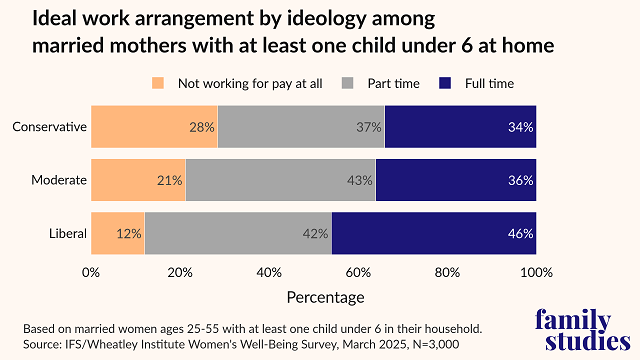

What’s more: when we look at work-family ideals for mothers by ideology and partisanship, we find that most conservative and Republican married mothers of young children would like to be at home full-time or work part-time.

By contrast, a plurality of liberal and Democratic married mothers of young children aim to work full-time (28% of conservative mothers in this group would like to be at home full-time and 37% part-time, whereas 46% of liberal moms would like to work full-time).

Across America, most married mothers of young children do not aspire to be Supermom—instead, they are hoping to be super mothers by not working at all outside the home or by working part-time.

It’s also worth noting that the most popular option among married mothers of young children, in general, is part-time work: overall, 41% of married mothers of young children in America prefer part-time work.

Why Part-time Work Appeals to Moms

These patterns are largely consistent with what the British sociologist Catherine Hakim would expect. In her work on women’s work and family preferences, Hakim has argued that there are three types of women: “work-centered” women who focus on career, “adaptive” women who have more of a family orientation but also aim to keep a foot in the workplace, often on a part-time basis, and “home-centered” women who desire to focus their lives on the home.

In her “preference theory” about women, Hakim correctly argues that culture, economics and public policy shape which of these groups is more popular among women, but she also notes that the “adaptive” strategy — which prioritizes part-time work —is often the most popular preference for women.

Her theory could not be more relevant here in America. What’s clear is the ideal and real-world arrangements of conservative mothers across America — not to mention moms of other ideological persuasions — cannot be generalized from a small group of right-leaning women working largely in Washington, D.C. or the media.

The truth is that being a “Supermom” who combines a high-flying career with an active family life is neither the reality nor the ideal for ordinary conservative women outside the Beltway, and neither is stay-at-home motherhood a gilded option reserved for the wealthiest households. Across America, most married mothers of young children do not aspire to be this sort of Supermom—instead, they are hoping to be super mothers by not working at all outside the home or by working part-time.

This part-time option, which also encompasses moms with side hustles, is especially appealing to conservative, Republican, and middle-of-the-road mothers of young children. But this adaptive option is also the one that seems hardest to realize in the real world, and the appeal of part-time work is a story that is not being told enough in today’s conversations about women juggling marriage, motherhood, and work.

Autumn Zeoli is an intern with the Institute for Family Studies and is pursuing a Master’s in Public Policy at the University of Virginia. Brad Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and a Deseret News contributor. Ken Burchfiel is a research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies.

Editor's Note: This article appeared first at Deseret News and has been reprinted here with permission.