Executive Summary

Does marriage matter for fertility? Around the world, a growing share of births are to unmarried mothers. Public opinion polls show fewer and fewer people believe that parents need to be married. Many commentators assume that the historic link between marriage and childbearing is now broken. Some go further and claim that policymakers may be wise to ignore marital status as an important element of the fertility process. In related arguments, low fertility in East Asia, attributed to strong stigma against unmarried motherhood, is thought to be remedied by destigmatizing nonmarital childbearing and de-prioritizing marriage.

Our new report, published jointly by the Institute for Family Studies and the Wheatley Institute, challenges these ideas. Marriage still matters for fertility; indeed, marital behaviors remain closely tied to fertility behaviors, so much so that it is virtually impossible to promote marriage or fertility alone without also influencing the other.

We demonstrate the consistent importance of marriage for fertility using three methods:

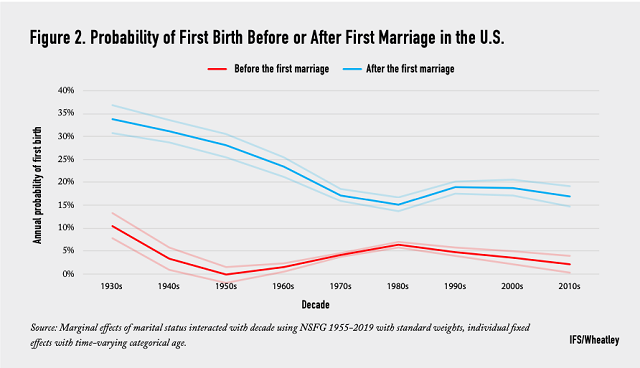

1. First, across several cohorts of U.S. women, we show how the odds of marriage increase upon childbirth, and how the odds of childbirth increase upon marriage. That is, getting married still boosts childbearing today as it did in the past (and having a child boosts the odds of marriage).

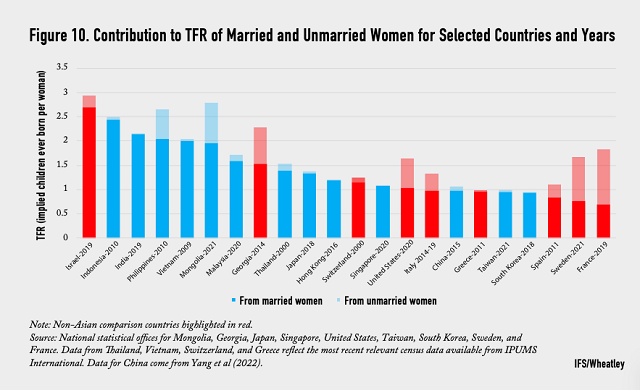

2. Next, we explore the observed empirical relationship between changes in marriage and changes in fertility rates in OECD countries and find that later marriage tends to mean lower fertility. Nonmarital fertility does not fully compensate for lost marital births.

3. Finally, with a detailed quantitative analysis of fertility in select Asian and other countries, we find that common stories about Asian fertility are incorrect. While nonmarital fertility in Asia is low, marital fertility in Asia is also unusually low, suggesting that factors broader than stigma against nonmarital fertility must be driving low fertility.

While our report demonstrates that marriage and fertility are closely linked, whether the link is causal is not always clear. As shown especially in the NSFG data, while marriage does boost fertility, fertility also tends to lead to marriage. Because marriage and childbearing are linked in individual minds and plans, desire for children can motivate marriage, even as desire for marriage can motivate childbearing. But causality running both directions should not be construed to mean that the existence of either causal pathway is in doubt: it is clearly the case that changes to fertility or marriage behavior cause changes in the other behavior. The causal links between marriage and fertility are complex and bidirectional but undeniably important. As marriage is relinquished or postponed, so, too, is childbearing.