Highlights

- In many countries where child care is technically cheaper, like Korea or Japan, it is less available. Post This

- A recent survey conducted by Demographic Intelligence found that among women who ever intended to have more children, the cost of child care was one of the largest concrete worries. Post This

- Spending more on child care might not actually reduce the childcare costs that burden families. Post This

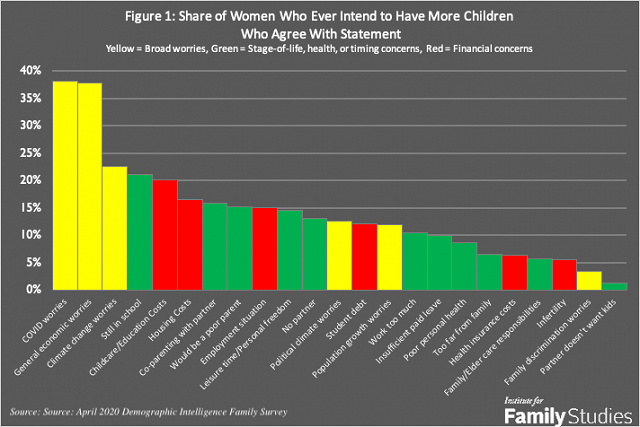

Child care costs are one of the largest barriers between families and their desired family size. A recent survey found that vast majorities of young, would-be parents see affordable child care as an important precondition to achieving their family goals. A 2018 New York Times/MorningConsult poll found that, among individuals who had fewer children than they desired, child care costs were the most commonly-cited reason for that deficit. An April 2020 survey conducted by Demographic Intelligence1 found that among women who ever intended to have any more children, the cost of child care was one of the largest concrete worries cited by would-be parents, on par with worries about climate change, housing costs, concerns about unequal sharing of household responsibilities, or a desire to avoid childbearing while still in school.

Child care costs are a real problem for families. Policymakers who want to help families achieve their goals (and thereby incidentally increase the national birth rate) would do well to implement low-cost options. Or, so goes the argument: advocates and policymakers have pushed for either publicly-run or supported, expanded day care for many years, with the putatively pro-natal benefits of these programs being a recent addition to the list of reasons why taxpayers should pay it.

However, the story is more complicated. First of all, the putative benefits of early child care may not be real. A recent study found that early-childhood interventions are not any more cost-effective as tools to improve economic well-being than later-in-life interventions, as others here at IFS have outlined. Furthermore, for many kids, universal childcare may actually have a negative impact in some cases, as has been found in the case of Quebec’s universal childcare program. And while I have shown in the past that spending on public child care does often boost birth rates, it’s a far more expensive strategy (in terms of dollars spent per baby born) than giving families direct cash payments. An academic study of 18 OECD countries from 1982 to 2007 found that, while increased generosity of maternity benefits or child allowances was unambiguously associated with higher subsequent birth rates, child care spending had a more mixed effect. Even in cases where birth rates did rise, child allowances were about nine times as cost effective as day care.

But this creates a conundrum: given the survey-reported importance of child care costs, why are child care subsidies so ineffective at actually helping families achieve their childbearing goals?

One reason is that public spending on child care doesn’t always go to families. For example, over half the value of the U.S.’ child care tax credit just goes to inflating the price of child care. The only way that child care spending by the government actually reduces costs to families is if the government achieves a near-monopoly and establishes very strict cost controls. But if the government instead participates in a mixed market, government funds could be substantially captured by private day care providers. While in some countries governmental near-monopoly on child care exists, in America, efforts to establish such a monopoly would run headlong into numerous obstacles, not least the constitutionally-protected status of religious education. Since a recent Supreme Court case found that religious educational institutions have equal access to public funds, it’s unlikely any court in the near future would support the closure of religious day cares.

Moreover, the reason that American women cite “cost of child care” as major concern is that while child care is available, it’s simply very costly. In many countries where child care is technically cheaper, it is less available: Korea and Japan both run highly-subsidized child care programs, but because these programs are government-run or tightly regulated, the supply is tightly limited. Thus, Korean and Japanese women are availability constrained.

This issue is not hypothetical: it turns out that the expansion of universal pre-K in the United States has crowded out a lot of home-based care even for younger children, actually making infant care more expensive. Essentially, most private daycares undercharge for the youngest children, who require the most care, and make it back on older 3 and 4-year-old kids. But since the public sector has expanded to 3 and 4-year-olds, many private day cares have been unable to keep their doors open, and prices and waitlists for younger kids have exploded.

In other words, spending more on child care might not actually reduce the childcare costs that burden families. Government spending could be gobbled up by private players, the expansion of government services could distort other segments of the market, and the displacement of more dynamic private options could lead to even longer waitlists than parents currently face.

There’s another spillover effect. For families that already use or desire child care services, government subsidy for or provision of those services will indeed ease their budget. Depending on how it’s measured, these families could make up anywhere from 20 to 75% of potential new parents.

But that leaves a large share of families who probably don’t want to use child care services, who would prefer to care for their children at home. Their ability to achieve this preference may be influenced by public policy choices related to child care. If a given neighborhood has four families with children under age two and all four are cared for at home, it’s fairly easy to organize parent-sharing, giving every caretaking parent opportunities for rest and other tasks. Furthermore, staying at home with a child is a far less isolating experience if others nearby are doing the same.

Most low-income families would be better off with a $250 per month child allowance than a $250 per month discount on child care.

However, if three of those families have their kids in full-day day care, and all the would-be caretakers are working, the one family choosing at-home care faces considerably diminished circumstances. Whenever a parent stays home to be a caretaker, he or she would face a far more stressful and isolated situation, with fewer opportunities for rest and burden-sharing. In simple terms, it’s easier to raise kids with more adults around to help.

Parents who desire to care for their children at home may also simply be parents who enjoy children more and are likely to end up having more kids. Pushing these households towards less time with their kids and more attachment to the workforce is almost certainly anti-natal. Thus, one possible explanation for the weak association between childcare and childbearing could be that public support for childcare does help some families but disrupts the informal networks of support that other (possibly more fecund) families depend on.

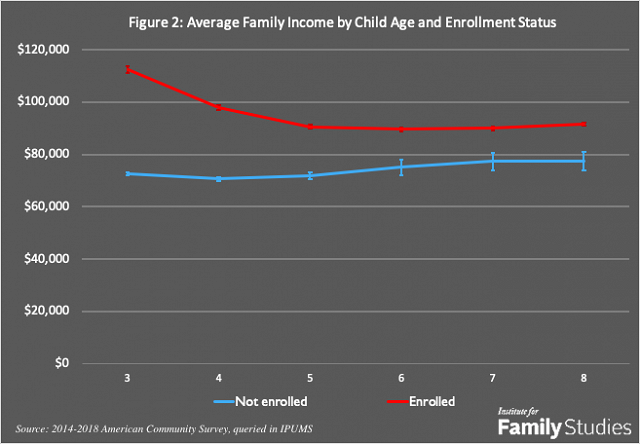

Finally, there is a fundamental concern of fairness involved in government subsidized child care. The families who use the most child care will be those where all parents have relatively high-earning “outside options.” Publicly supported child care is inherently a subsidy to employed people. One of the common justifications for public child care is that it will encourage more parents (especially women) to participate in the labor force, an effect which rests entirely on the assumption that families will recognize that the child care benefit is a subsidy primarily provided to people who have less economic need. The figure below shows the average family incomes of children who were enrolled in school or center-based care at each age versus those who were not.

Kids enrolled in child care programs come from richer families than other kids. Plowing more public funds into early education isn’t about helping poor kids get ahead; it’s about helping the upper-middle-class stay ahead. Especially since the evidence that early child education actually helps child outcomes is razor thin (as noted above), it can’t be argued that subsidies for these programs are part of an effort to close attainment gaps: early child education doesn’t reduce attainment gaps any more than later programs. The main reason child care gets attention as a political issue is that it is a major cost for the upper-middle-class, aspirational, two-earner households who dominate public discourse. But these families are already heaped with social and economic advantages; handing them free child care that may not do their kids any actual good and may harm the communities other, poorer parents depend on isn’t good public policy.

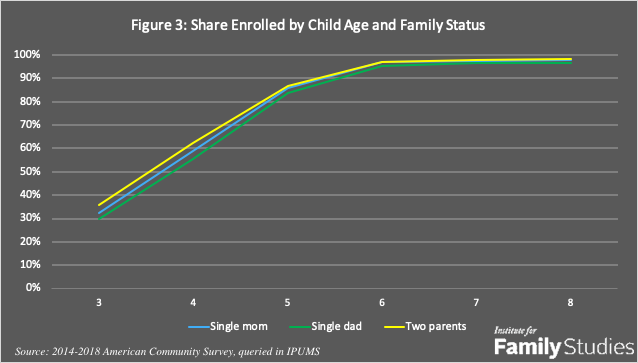

The second reason child care gets political attention is that it is often believed to be a major cost for single parents, who make up a large share of parents. And yet, single parents are less likely to have their children enrolled in a school or center-based care at ages 3, 4, or 5.

Now, it is possible that these parents would like to enroll their kids and then be able to work. But child care is hardly the only case of a financial burden landing with disproportionate force on single parents, who face more hurdles across the board.

That is, in fact, why publicly supported child care is such an inadvisable policy. The families with the greatest financial needs often face numerous difficulties, not just one big cost. They are better served with direct cash transfers, rather than in-kind benefits. Most low-income families would be better off with a $250 per month child allowance than a $250 per month discount on child care.

Families need help to achieve their childbearing goals. Society benefits from families achieving these goals, as we need a next generation of taxpayers and workers to keep the gears of civilization moving as the present generation ages. The challenges facing families are largely financial in nature, so society’s support will need to come in the form of meaningful financial support. But subsidized or free child care isn’t a very useful way to deliver that support. It provides numerous opportunities for middlemen of various kinds to take their cut, limits the choices available to families, has perverse effects in many areas, gives the most aid to the least needy families, and doesn’t help families with most of their financial challenges. For all these reasons, a simple child allowance is a vastly preferable policy.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a market forecaster for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

1. The author is the chief information officer of Demographic Intelligence, a for-profit consultancy firm.