Highlights

- Although the Scott-Burr plan does a much better job of ensuring that federal support for child care does not discriminate against independent preschools, it discriminates against middle- working-class families that would like to have a parent at home. Post This

- By seeking to expand eligibility for child care subsidies into the middle class without including any subsidies for stay-at-home parents, the Republican proposal could push hundreds of thousands of kids into institutional daycare. Post This

Too often, Republicans succumb to the temptation to take a Democratic policy priority, trim down its scope, spend less, tweak it a little, and, voila, try to pass some Democrat-lite measure off as an authentically conservative alternative. That’s what Sens. Tim Scott and Richard Burr are, in essence, doing with a new bill to reauthorize the Child Care and Development Block Grant.

In this case, the Scott-Burr legislation ends up trying to breathe new life into President Joe Biden’s ill-fated “Build Back Better” bill, which would have spent more than $200 billion on subsidizing child care for millions of poor and middle-class families.

Not content to let Biden’s bad and discriminatory child care agenda die a quiet death, Scott, R-S.C., and Burr, R-N.C., are now proposing to revitalize the central tenet of that agenda by expanding eligibility for child care subsidies not just to poor families, which is what the current block grant does, but also to middle-class families. The problem is that this bill would end up steering thousands of dollars in child care subsidies to middle- and working-class families with two parents in the labor force and offer nothing to similar families who have made a considerable financial sacrifice to have one parent at home.

Families like the one headed by Jeremy and Ashley Fannin of Clayton, North Carolina, would get zilch under the bill being championed by the senators from the Carolinas. Under their bill, families making up to 150% of their state’s median income could be eligible for thousands of dollars in child care subsidies. In North Carolina, that’s about $140,000 for a family of five like the Fannins. But because the Fannins are sacrificing to have Ashley stay home and care for their young children while Jeremy serves in the military, they would be eligible for nothing under the Scott-Burr plan.

In an email, Ashley Fannin told us this is a “frustrating policy for those of us who have chosen in this season of life to have a parent stay at home,” noting that they are living on a modest military salary right now. She added, “I also feel that a parent’s job within the home is one of the most important so to not recognize that or to help make it more of a possibility for parents would be unfair.”

It is also unwise. Scott, Burr and other Republicans supporting this measure — from Sens. Susan Collins, R-Maine, to Shelley Moore Capito, R-WVa., to Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa —haven’t done their homework on the research on child care and child well-being. By seeking to expand eligibility for child care subsidies into the middle class without including any subsidies for stay-at-home parents, the Republican proposal could push hundreds of thousands of kids into institutional daycare. They seem ignorant of the effects of a similar child care expansion on children north of the border.

Research done by MIT economist Jon Gruber and his colleagues found that Quebec’s push to massively expand child care subsidies was linked to “worse health, lower life satisfaction and higher crime rates later in life” for the young children exposed to this new policy, with the subsequent “impacts on criminal activity … concentrated in boys.”

Vox, by no means a conservative outlet, summarized the effects of Quebec’s child care push in this way: “Quebec gave all parents cheap daycare — and their kids were worse off as a result.”

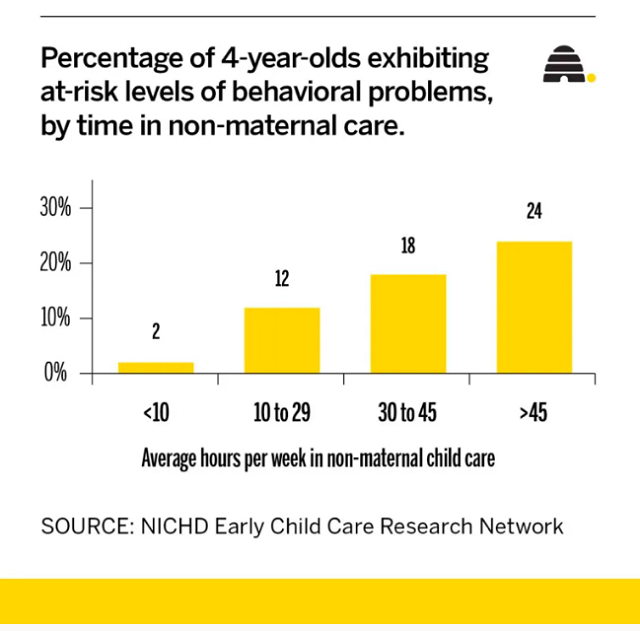

Closer to home, a big longitudinal study from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development found that extensive hours in day care for young children, starting in infancy, were associated with negative social-emotional outcomes for kids. By age 4 1/2, children who had spent more than 30 hours per week in child care were significantly more likely to experience negative outcomes like behavior problems and conflict with teachers at rates three times higher than their peers.

For instance, just “2% of children who averaged less than 10 hours per week exhibited behavioral problems, compared to 18% of those who averaged 30 hours or more and 24% of those who averaged 45 hours or more per week,” observed Jenet Erickson and Katherine Stevens, adding, “The negative effects associated with extensive hours in child care rivaled the effects of poverty.”

More generally, the research tells us that — so long as they have the benefit of a healthy, two-parent home — babies and toddlers are more likely to flourish when they have the benefit of being cared for primarily in the home. Parents intuitively seem to understand this reality. Surveys of American adults consistently find that parents do not think full-time, out-of-home child care is ideal for their children. Most recently, only 11% of full-time working mothers said using center-based child care is the best arrangement for children under age 5. What they wanted most was a model of flexible work where both parents share care (37%), followed by a model where one parent stays home full time (27%), relatives provide child care full time (14%), or one parent stays at home part time (12%).

Those preferences aren’t misguided. In fact, the highest quality standards for child care programs promote exactly what happens in the average home — one adult in an active, stable and encouraging relationship with two to three children. This standard is difficult to duplicate in institutionalized child care settings, especially on a large scale.

Morever, working-class and middle-class Americans like the Fannins are most likely to prefer a model with one parent working full-time and the other providing at-home child care. Of course, some of these families put their kids into full-time child care because they have to, but the clear majority would prefer not to. Government assistance in the form of tax credits and cash assistance are strongly preferred by these families because they enable parents to choose the arrangement they think is best for their kids.

A major problem with Biden’s “Build Back Better” was that it would have created a new entitlement program that denied parents the opportunity to choose the best way to care for their young children. Although the Scott-Burr plan does a much better job of ensuring that federal support for child care does not discriminate against independent preschools (including religious ones), it makes one of the same mistakes “Build Back Better” made: It discriminates against middle- and working-class families that would like to have a parent at home.

We don’t need a “lighter” version of “Build Back Better” from our Republican leaders. Just building a child care plan that gives parents more choices outside of the home does not make something conservative. If they are interested in building a “Parents’ Party,” Republicans like Scott and Burr need to go back to the policy drawing board.

A more generous tax benefit for parents, such as the one proposed by Sens. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, or Josh Hawley, R-Mo., would give parents more resources to choose what kind of situation fits their needs best, rather than giving parents benefits they can only use on nonparental care. A Republican family policy agenda should give parents more choices about how best to care for their children, rather than backing an agenda that discriminates against families dedicated to caring for their young children at home — like the Fannins of North Carolina.

Jenet Jacob Erickson is a fellow of the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University. Brad Wilcox is a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared at The Deseret News. It has been reprinted here with permission.