Highlights

- 73% of the students attending highly-selective colleges came from married-birth-parent families. Post This

- Students from married birth parent families are more than twice as likely to graduate from a selective college as those from all other family types. Post This

- One major privilege that affects whether or not a student graduates from a selective college is whether or not they were raised by their own married parents. Post This

Nowadays, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, there are few, if any, students on the campuses of American colleges and universities. But someday students will return to Stanford, Harvard, Princeton, Duke, Yale, the University of Virginia, MIT, the University of Chicago, and all the other highly selective private and public institutions in the U.S.1 And with them will come a parade of prospective students and their parents, trying to decide where and whether to apply. When they do, they will find student bodies much different in composition from what they would have found a half-century earlier.

Young women are now a majority on most campuses. And there are many more students from racial and religious backgrounds other than white Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Yet, despite the efforts of college administrators to make their institutions more diverse and inclusive, the majority of students at selective colleges share several notable similarities. More than two-thirds have parents who earned college, graduate, or professional degrees themselves. Nearly three- quarters come from families whose annual incomes are above—usually well-above—the median for all families with children. And three-quarters of these students are white.2

There is one other attribute that a large majority of students at selective colleges share, an attribute that is rarely noted or remarked upon. That is, they were raised by their married birth parents. This may be seen in data from a large longitudinal study conducted by the U.S. Department of Education beginning in 2002. The study followed a nationwide sample of some 13,000 high school sophomores for 10 years, up to 2012, collecting information on the students’ educational attainment and employment histories.3

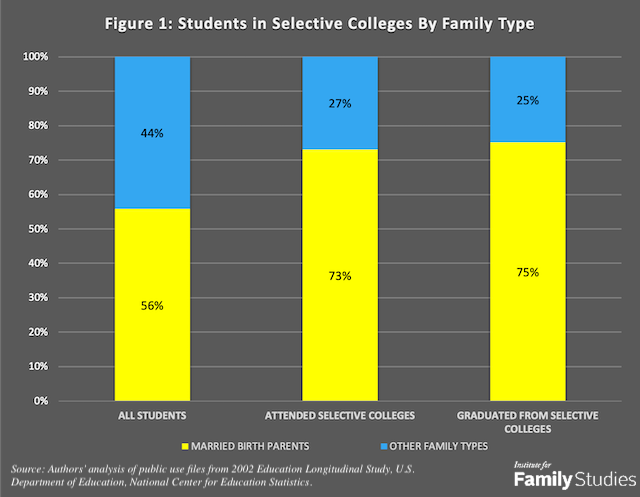

At the start of the study, when the students were all high school sophomores, little more than half of them—56%—were living with married birth parents. The remainder were living in a variety of other arrangements: with single or remarried birth parents, cohabiting birth parents, or grandparents, foster parents, or adoptive parents. As we showed in a prior IFS research brief,4 students living with married birth parents were more likely than those from all other types of families to attend and graduate from four-year colleges. The same held true for attending and graduating from highly-selective colleges (“highly-selective colleges” are those whose first-year students’ test scores placed the schools in the top fifth of baccalaureate-granting institutions).

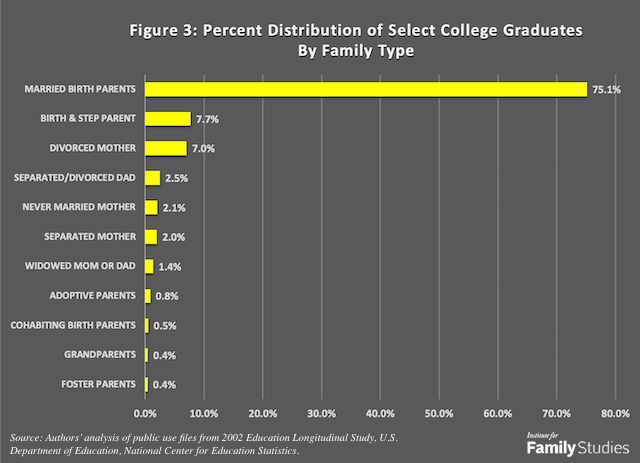

As a consequence of the different rates of college attendance and graduation, 73% of the students attending highly-selective colleges came from married-birth-parent families, as shown in Figure 1. And 75% of those graduating from these colleges were from the same type of conventional two-parent family, as shown in Figures 1 and 3.

Note: Percent distributions of students by family type: All U.S. high school sophomores in 2002;

students who attended highly selective colleges; and students who graduated from highly selective colleges.

Why are children of married birth parents over-represented among select college attenders and graduates? Part of the reason is that these families have higher parent education levels, higher family income levels, and larger proportions of Asian and white students than do other family types. And each of these factors—parent education, family income, and racial/ethnic background—is associated with a student’s grade point average in high school5 and his or her performance on standardized tests of academic achievement.6 The combination of a high GPA and top SAT or ACT score is what typically gets you into a highly selective college. The same GPA-test score combination is also the strongest predictor of graduating and earning a bachelor’s degree from a selective college.7

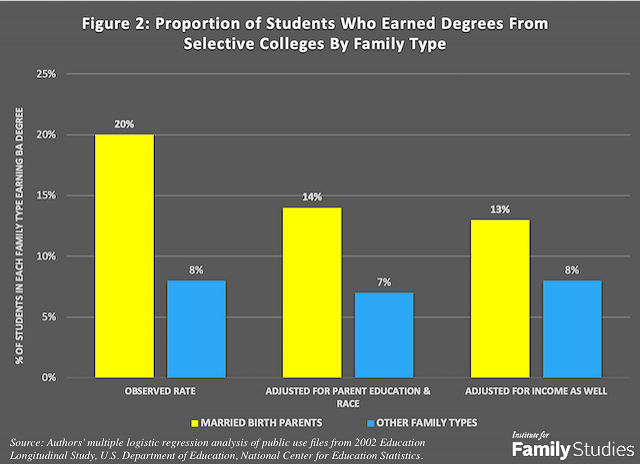

Yet, even after controlling for parent education, family income, and student race and ethnicity, being raised by one’s married birth parents provides an additional boost to one’s chances of getting through Princeton. As shown in Figure 2, students from married birth parent families are more than twice as likely to graduate from a selective college as those from all other family types (20% vs. 8%).8 Those are the observed relative graduation rates, before any adjustment for differences in family background characteristics. Using regression analysis to equalize the parent education levels and racial composition of the two groups, the adjusted graduation rates become 14% compared to 7%, still twice as great. Equalizing average income levels as well reduces the difference in rates further, to 13% and 8 percent.9 Yet the adjusted graduation rate for students from intact families is still significantly higher than for those from disrupted or never-married families even after controlling for income, parental education, race/ethnicity, and sex.

Bear in mind as well that substantial reductions in family income are a reliable consequence of family breakup or non-formation. That’s because families headed by stably married parents are generally able to marshal more income and more savings to spend on college than are non-intact families, especially families headed by single parents.10 So, controlling for family income is actually taking away some of the beneficial effects of marriage and family stability.

Note: Graduation rates from selective colleges for students from married birth parent families

and students from other family types: observed rates; rates adjusted for sex, race of students,

parent education level, and family income.

Students in highly-selective colleges are also especially likely to come from intact families because such families tend to provide young people with the motivation and support that enable them to achieve higher grades and handle rigorous college coursework. Intact families typically afford students more involved fathers, more residential stability, and more consistent parental affection and discipline, all of which are conducive to students stearing clear of the principal’s office and excelling in school, thereby putting them on the path to a school like Princeton.11 It turns out, then, that one major privilege that affects whether or not a student graduates from a selective college is whether or not they were raised by their own married parents.

Efforts to “open up” colleges to students from a range of family backgrounds are commendable. But they should be accompanied by parallel efforts aimed at ensuring that a much greater share of future generations of young people have the privilege of being raised in stable and strong families that nurture their social, emotional, and intellectual development.

Note: Percent distribution by detailed family types of U.S. high school sophomores in 2002

who graduated from highly selective colleges.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce. W.Bradford Wilcox is a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

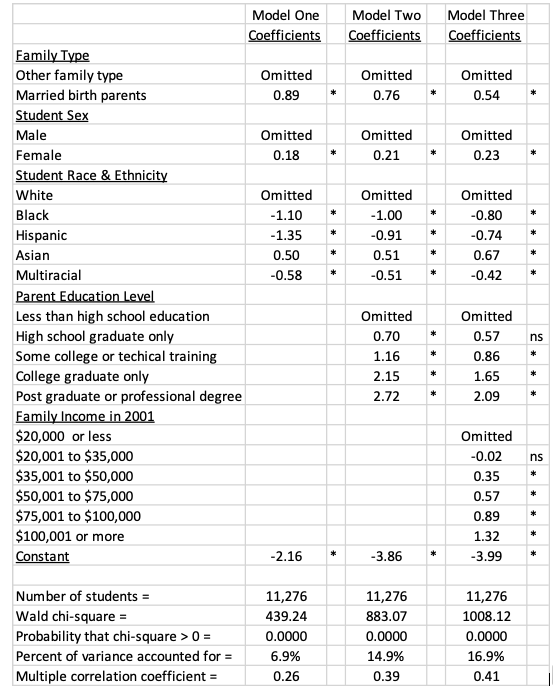

Appendix

Table 1 (A)

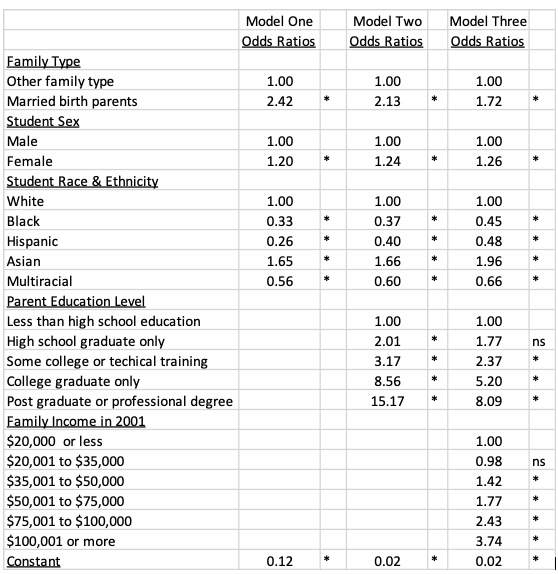

Note: Multiple logistic regression analysis of graduation from highly selective colleges

as associated with family type, student sex and race and ethnicity (Model One);

parents’ education level in addition (Model Two); and family income in addition (Model Three).

Source: Author’s analysis of public use data from the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002,

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Table 1 (B)

Note: Multiple logistic regression analysis with odds ratios of graduation from

highly selective colleges as associated with family type, student sex and race and

ethnicity (Model One); parents’ education level in addition (Model Two);

and family income in addition (Model Three). Source: Author’s analysis of public use data

from the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002, U.S. Department of Education,

National Center for Education Statistics.

1. The named universities are among those with the lowest acceptance rates in 2018, according to U.S. News and World Report.

2. Figures based on authors’ analysis of data from the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002.

3. Ibid.

4. Nicholas Zill, For Getting Kids Through College, Single Parent Families Are Not All the Same, Institute for Family Studies, May 2020.

5. A regression equation that combines parent education, family income, and student sex and race and Hispanic origin accounts for 20% of the variance in high school GPA (R = .44). The addition of family type to the regression increases the variance accounted for by 2.2%, to 22% (R = .47).

6. A regression equation that combines parent education, family income, and student sex and race and Hispanic origin accounts for 25% of the variance in students’ composite scores on tests of reading and math achievement in high school (R = .50). The addition of family type to the regression increases the variance accounted for by 2.1% to 27% (R = .52).

7. A logistic regression equation that combines high school GPA and students’ composite scores on tests of reading and math achievement accounts for 29% of the variance in whether or not students earn bachelor’s degrees from highly selective colleges (R = .54). Adding family characteristics to the regression increases the variance accounted for by 3.4% to 33% (R = .57).

8. The overall proportion of students earning degrees from highly selective colleges was 15%.

9. When only race and sex are controlled, the odds of students graduating from highly selective colleges are 2.42 times higher if they come from married birth parent families than if they come from non-intact families. When parent education is controlled as well, the odds become 2.13 times higher. And when, in addition, family income is controlled, the odds become 1.72 times higher. See summary of logistic regression analysis in the Appendix.

10. Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1994); Robert Lerman and W. Bradford Wilcox, For Richer, For Poorer: How family structures economic success in America (Charlottesville/Washington, DC, IFS/AEI: 2014). IFS/AEI. Robert I. Lerman, Joseph Price, and W. Bradford Wilcox, “Family Structure and Economic Success Across the Life Course,” Marriage & Family Review 53, no. 8 (2017): 744–58.

11. Op. Cit., McLanahan and Sandefur; Paul Amato (2005). “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation,” Future of Children, 15, no. 2: 75-96; Nicholas Zill and W. Bradford Wilcox. The Black-White Divide in Suspensions: What Is the Role of Family? November 19, 2019.