Highlights

- Polls consistently show that Americans consider porn morally and socially problematic—a sign that more aggressive enforcement or careful regulation of existing laws might be more popular than some might expect. Post This

- Self-identified "liberal" women are almost as likely as "conservative" men to support a porn ban. Post This

- While Americans don't support an outright ban on porn, they are far from porn-friendly. Post This

Is the Trump administration about to declare war on porn? If several congresspeople have their way, the answer is yes. Earlier this month, four members of the House of Representatives wrote to Attorney General William Barr, asking him to fulfill a Trump campaign promise and enforce federal obscenity laws against the porn industry.

"Given the pervasiveness of obscenity it's our recommendation that you declare the prosecution of obscene pornography a criminal justice priority and urge your U.S. Attorneys to bring prosecutions against the major producers and distributors of such material," the group wrote in a letter obtained by National Review.

Prompted by the letter, over the past several weeks, the Right has been riven by internal debate over regulating or banning pornography. On one side are small-government libertarians, who say the risks of porn are overblown, and that keeping it out of the hands of kids is a job for parents, not government. On the other are an increasingly vocal cohort of traditionalists who support aggressively regulating or banning porn.

As with many intra-conservative spats, this debate runs the risk of coming unmoored from political reality. Maybe six guys on Twitter want to hang pornographers, and six other guys want to put pornographic mags in the checkout line next to the candy. But what do Americans, as a whole, think about porn?

The answer, survey data show, is complicated. While a declining minority of Americans support an outright ban on pornography, that does not mean we consider the stuff unproblematic. Rather, polls consistently show that Americans consider porn morally and socially problematic—a sign that more aggressive enforcement of existing laws, or careful regulation, might be more popular than some might expect.

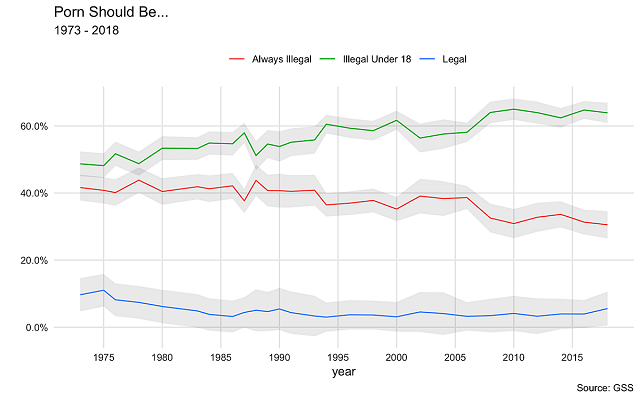

The most concrete data on public opinion about an outright porn ban comes from the General Social Survey, which asks respondents if porn should be illegal to all, should be illegal to those under the age of 18, or should be legal.

The results are pretty clear: since the question was first asked in 1973, a plurality has always said that porn should only be illegal for kids. The gap between that plurality and those who say it should be totally illegal has only grown: in 1973, 41% wanted a full ban compared to 48% who wanted it illegal under 18. In 2018, those figures are 31% and 65%, respectively.

Agitate as some might, then, there is minimal democratic appetite for banning porn altogether (and that's ignoring the Constitutional issues). But does that mean that Americans are chill with porn, as long as kids nominally cannot watch it? Maybe not.

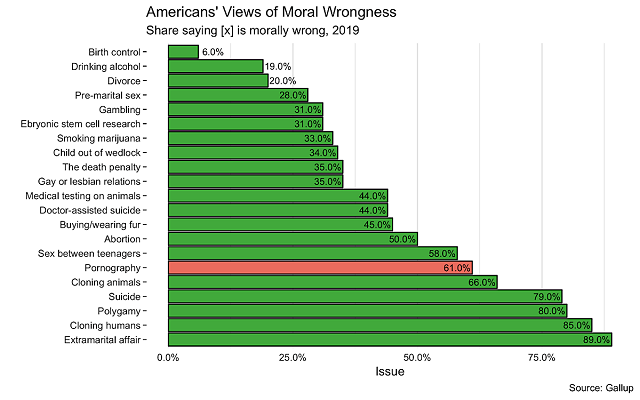

Gallup routinely polls Americans on their views on the moral acceptability of certain issues, including pornography: 61% of respondents to its 2019 poll said that porn was morally wrong. By way of comparison, that percentage is on par with the share who believe smoking marijuana (65%) or engaging in same-sex relationships (63%) are morally acceptable. Porn was less likely to be considered morally acceptable than physician-assisted suicide, gambling, abortion, and drinking alcohol—all of which Americans generally support at least some regulation.

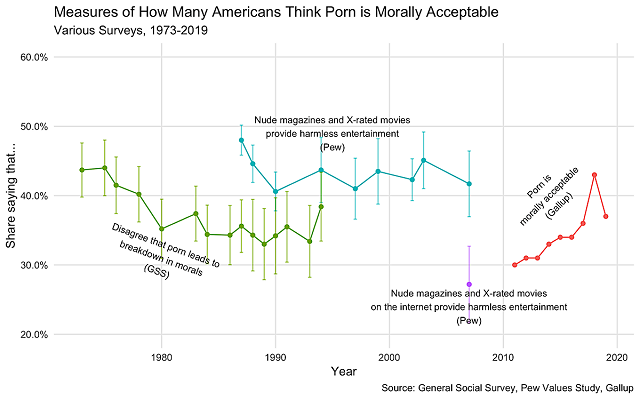

Gallup has been asking about porn's morality since 2011 and, with one outlier, the share who say porn is morally acceptable has stayed under 40 percent. But we know Americans have grown less likely to say we should ban porn—have they also grown less likely to say porn is immoral?

There is no continuous data on this question, so we can't know for certain. But we can cobble together several surveys to try to get a bigger picture. Between 1973 and 1994, the GSS asked respondents if they believed that pornographic materials lead to the "breakdown of morals." Between 1987 and 2007, the Pew Values Survey asked if "nude magazines and X-rated movies provide harmless entertainment for those who enjoy it."

Putting together these three data sets does not conclusively reveal Americans' changing views on porn's morality. But assuming that the three questions at least correlate, we can note some degree of consistency. Between 1973 and 2018, across all of our measures of popular perception, between 30 and 45% of Americans thought some version of "porn is morally acceptable," always less than a majority.

One other interesting, albeit outdated, fact shows up in the Pew data. In 2007, Pew polled two questions—the standard one about "nude magazines and X-rated movies," and one that appended "on the internet." Internet pornography, it turns out, was considered way worse than its offline counterpart—just 27% said it was "harmless entertainment."

While Americans don't support an outright ban on porn, then, they are far from porn-friendly. Majorities say it is immoral, a sentiment that, data suggests, may be consistent over the past several decades. And there is at least some evidence that internet porn is considered substantially worse than its old-fashioned counterpart.

Some might object that just because Americans think something is immoral does not mean they think it should be regulated. But, as mentioned, Americans are more likely to morally approve of lots of things—gambling, physician-assisted suicide, abortion—that they also support aggressive regulation of, or even bans on. Most Americans aren't libertarians, and are willing to tolerate some government oversight of things they are morally squeamish about.

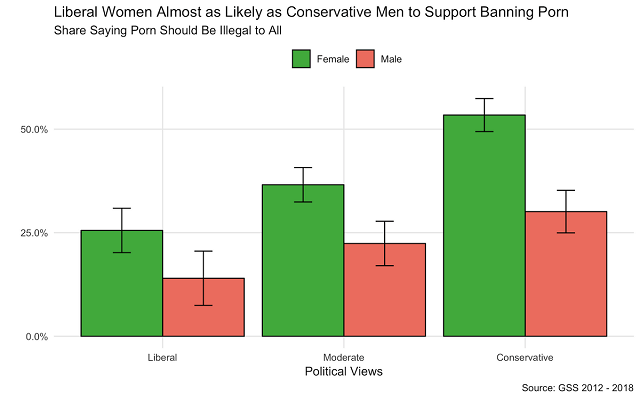

Data also provide some insight into who is most likely to get on board with banning or regulating porn. Using the GSS's measure of support for a porn ban as a proxy for greater support for regulation more generally, we can look at which demographic groups are most sympathetic.

Some of the results are unsurprising—the older you are, and the more right-leaning you are, the more likely you are to support a porn ban. But the most notable determinant might be sex: across every age group and political affiliation, women are significantly more likely than men to support a ban on porn. In fact, self-identified "liberal" women are almost as likely as "conservative" men to support a porn ban.

The survey data here show that Americans do not want to ban porn. But they do think it's immoral—a view majorities have taken consistently over time. Women, in particular, appear to be a powerful constituency for pornography control.

All of that suggests that there may be some appetite for expanded regulation of pornography. More active prosecution of already existing obscenity laws, as the letter called for, is one option. Another is the approach outlined by Terry Schilling, Executive Director of the American Principles Project, in a November article in First Things: filtering at the ISP level, "domain zoning" porn sites to .xxx extensions, and stripping certain legal immunities from sites that publish obscene materials.

Such regulation would follow the approach that the late drug-policy expert Mark A. R. Kleiman called "grudging toleration," charting a course between full legalization and a full ban. "Grudging toleration" would focus on making acquiring pornography more onerous—e.g. through opt-in or credit card requirements—and targeting the worst of the worst actors (like market monopolist Mindgeek) with already existing regulatory authority.

Can the Trump administration get away with banning porn? Almost certainly not. But there is a lot of evidence that Americans, especially women, think porn is immoral. An agenda that zeroes in on those Americans' concerns, and targets porn's worst excesses, may be more successful than many libertarians imagine.

Charles Fain Lehman is a staff writer for the Washington Free Beacon, where he covers crime, law, drugs, immigration, and social issues. Reach him on twitter @CharlesFLehman.