Highlights

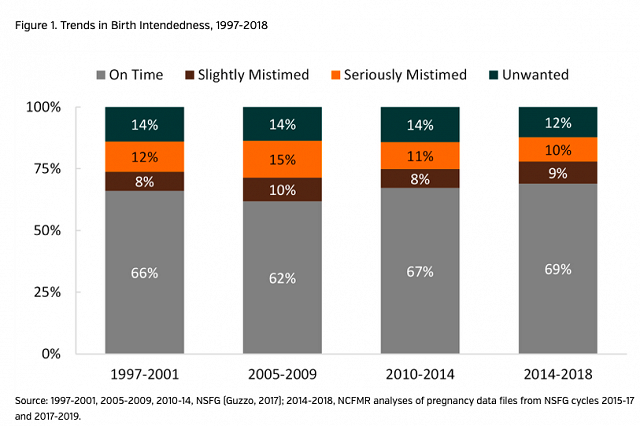

Fertility rates have declined considerably around the world in the last decade. In the United States, women report they desire two or more children, but in practice, they avoid having more than one or two kids. At the same time, however, there have not been similar declines in mistimed or unintended births. According to a recent series of Family Profilies by the National Center for Family & Marriage Research (NCFMR), examining birth intendedness between 1997 and 2018 with the National Survey of Family Growth, 31% of births were unintended between 2014 and 2018. Of these, two-fifths were “unwanted" (defined as "did not want any births at all or no additional births").

Who is Experiencing Unintended Births?

Although fertility rates have been falling steadily since 2007 among all women (especially racial minorities), unintended births occur most often among women who lack the social and economic resources to care for a child.

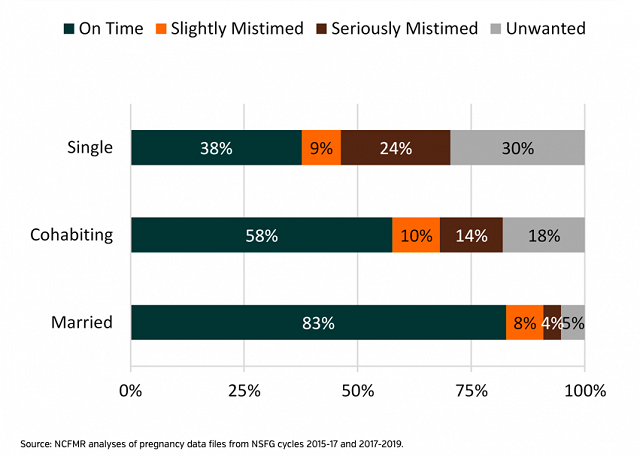

Mistimed births and “unwanted” births are significantly higher among single and cohabiting women than married women. As the NCFMR report explains, "In the late 1990s, unwanted births occurred most often among single or married women, with only one in five occurring to cohabiting women. By 2014-2018, only one in four such births was to a married woman, with the remaining split among cohabiting and single women."

- By 2014- 2018, 76% of “unwanted births” occurred among single and cohabiting women.

- While only 12% of births among married women are mistimed, nearly one-third of births among single women (33%) and 24% of births among cohabiting women are mistimed.

- Only 5% of births among married women are "unwanted," compared to 18% and 30% of births among cohabiting and single women, respectively.

- The share of seriously mistimed births (two or more years too early) was six times higher among single women than among married women.

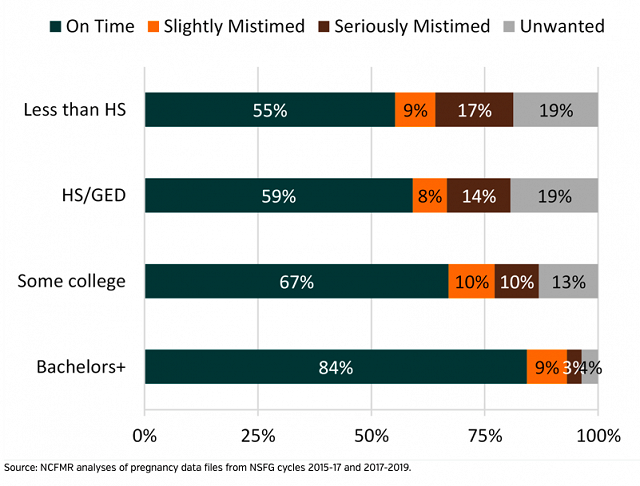

Unwanted or mistimed births are also more common among women with lower levels of education, as the figure shows below.

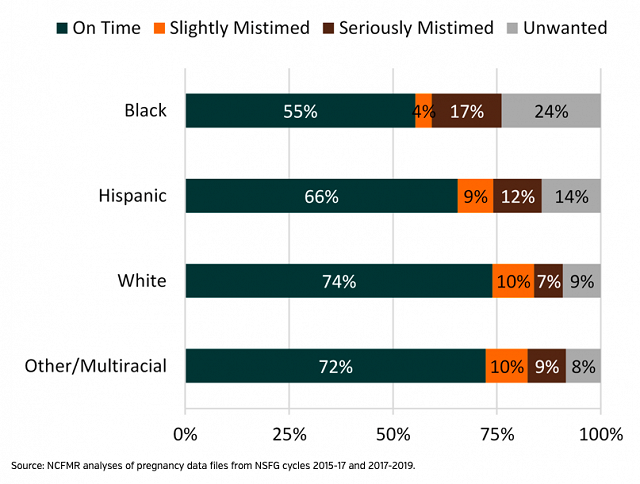

Birth intendedness does not differ substantially among racial groups, although "mistimed" births occurred most often to Black and Hispanic women. Black women also experienced the highest share of "unwanted" births, as shown in the figure below.

Why Do Low Income Women Keep Their Babies?

The majority of abortions are performed on poor or low-income women; however, disadvantaged women are more likely to carry out unintended pregnancies than highly educated “afluent” women. The reasons for this vary.

First, not all unintended pregnancies are unwanted. The qualitative work of Amber Lapp reveals that pregnancies are not always planned or unplanned. While middle class women tend to postpone childbearing to attend college and pursue a career, working class women are torn between academic and professional aspirations, and have strong family values. Their firm regard for motherhood and children results in less caution avoiding pregnancy, lower conviction to wait for a committed partner (who may or may not “exist”), and greater happiness if they find that they are expecting (even if the pregnancy was unplanned).

Second, the work of Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas in Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage, explains that distadvantaged women are more likely to consider abortion as immoral, are more likely to see pregnancy as something that will make their partner mature and commit, and are more likely to attribute great meaning to motherhood. Having a child allows them to love and be loved, and so empowers them to seek a better future.

Supporting Disadvantaged Mothers

The majority of women who courageously carry out “mistimed” or “unwanted” pregnancies are unmarried women with limited resources, who often also lack models of healthy family life. So how do we support these women and their children?

1. Strengthen Organizations That Assist Pregnant Mothers and Their Children

We should support non-profit initiatives that provide women facing unintended pregnancies with basic goods, emotional support, parenting classes, child care, and even temporary housing if needed.

2. Cultivate Family and Community Support

We should develop government programs that target both financial poverty and social poverty. As Dr. Sarah Halpern-Meekin previously explained to IFS, low income communities lack strong social ties with family and friends. This leaves them impoverished when they face major life transitions, such as starting a family, and weakens their mental and physical health. To relieve low income parents, it is important that programs include measures that build and strengthen relational bonds so that couples facing an unexpected pregnancy can parent to the best of their ability amidst financial troubles.

3. Enact Pro-Family Policies

We also need better family-focused policies to ensure that biological fathers share in the responsibility of raising their child, allow men and women to gain the skills they lack to earn a living wage, and that grant one of the biological parents paid leave so that they can care for their child when they most need their presence and nourishment.

4. Encourage and Promote Responsible Fatherhood

Finally, we know low income men and women hold family in high esteem, that children do better in two-parent family structures, and that men are better fathers when they are married to the mother of their children. We also know that lower income women often don’t have high hopes of finding a good husband and sometimes act as gatekeepers towards the fathers of their children. Therefore, we should strengthen programs that support men in their efforts to become the father they never had. To date, fatherhood programs have only had small statistically significant effects on paternal quality, and so further research is needed to develop programming that results in major quantitative effects. It might be especially beneficial for researchers to evaluate how religion helps individuals to overcome addictions, improve their behavior, and enjoy a more stable family life.

Maria Archer (Kaufmann) is Director of Youth Ministry for St. Bartholomew Catholic Church and is an independent contractor for the Marriage and Religion Research Institute at Catholic University of America, and a state leader for Canavox, a program of the Witherspoon Institute.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or viewpoint of the Institute for Family Studies.