Highlights

- American women had 5.8 million fewer babies over the last decade. Post This

- The lion’s share of “missing babies” would have been born to Hispanic moms. Post This

- Had birth rates remained at 2008 levels, 2019 would have been the first year when non-Hispanic whites did not represent a majority of new mothers. Post This

Fertility rates have fallen around the world over the last decade—even in countries with generous social welfare states, which experts had long expected to be holdouts in the face of fertility declines. But while demographers often talk about this change in terms of “fertility rates” or “births per woman,” another way to tally the total is in terms of missing births. That is, if the population of women who might have kids changed the way it did over the last decade, and if fertility rates had remained at their 2008 levels (the last time we had replacement-rate fertility in America), how many more babies would have been born?

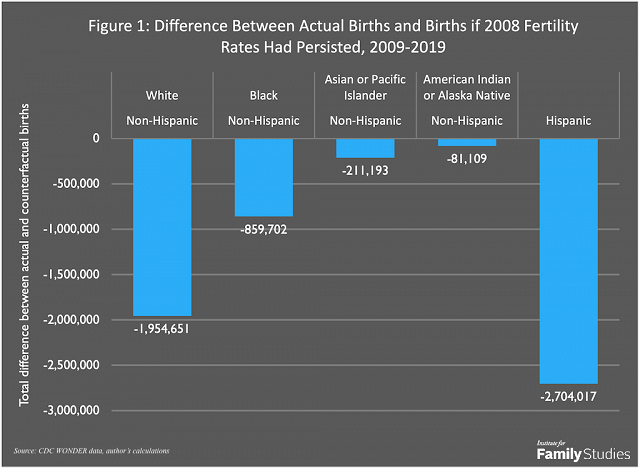

The answer is 5.8 million babies. Since births in the U.S. actually tend to run around 4 million per year, that’s almost like saying nobody had a baby for a year and a half. Figure 1 below shows the difference between the number of babies actually born to moms of each major racial or ethnic group tracked by the CDC from 2009-2019, and the number that would have been born, had 2008 fertility rates remained stable but underlying population totals changed in the same way.

The lion’s share of “missing babies” would have been born to Hispanic moms. That’s because in 2008, Hispanic moms could expect to have about 2.8 kids on average; now, they can expect to have about 2. Fertility rates declining by almost a third is a huge change, resulting in a loss of 2.7 million Hispanic babies that would otherwise have been born.

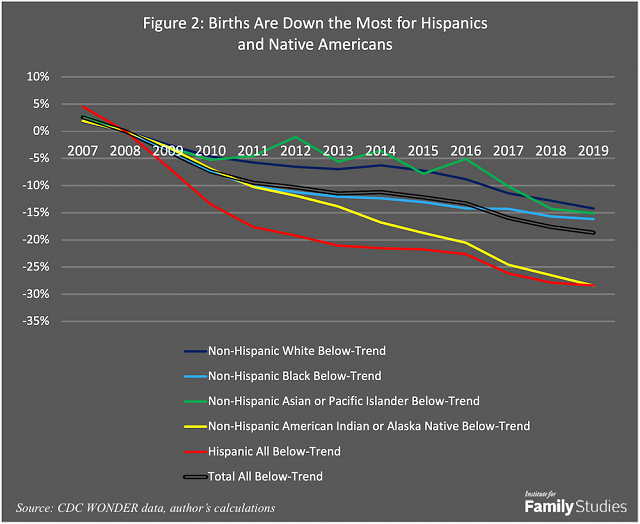

Non-Hispanic whites make up the second biggest category of missing babies, with almost 2 million missing births. But that’s a bit of an illusion: in fact, non-Hispanic white fertility rates experienced the least amount of decline of any group (from 1.9 children per woman to 1.6; Asian-Americans have always been lower, falling from 1.8 to 1.5). But the number of potential non-Hispanic white moms is very large. Figure 2 below shows the percentage difference between actual births each year, and the expected number of births for that group and year.

For ethnic minorities in America, birth rates have fallen sharply since 2007. Hispanic births in 2019 were almost 30% below the number that might have been born, or about 860,000 births. Indigenous peoples are similarly far below trend, totaling about 81,000 missing births, and 13,000 just in 2019. Although births have declined among non-Hispanic whites, it is not as severe. Among Asians, there are over 210,000 missing births, making 2019 births 15% below their expected value, yielding about 47,000 missing Asian-American births per year. Finally, for African Americans, there are over 850,000 missing births, with 2019 births running 16% below the stable-fertility scenario. Non-Hispanic white births in 2019 were just 14% lower.

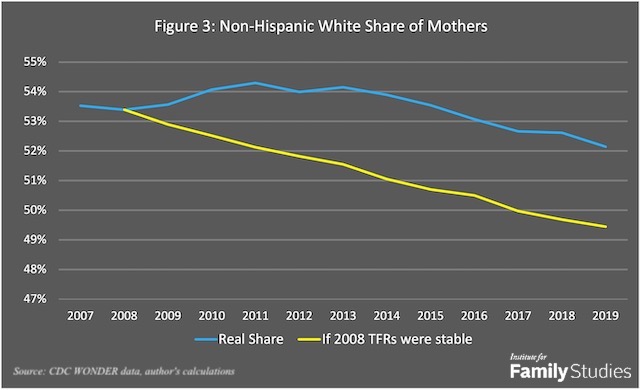

These changes have meaningful effects on the racial and ethnic mix of the United States. Had birth rates remained at 2008 levels, 2019 would have been the first year when non-Hispanic whites did not represent a majority of new mothers at about 49.5% of moms. But because fertility rates declined so much more for minorities than for non-Hispanic white women, instead, the non-Hispanic white share of births actually rose between 2008 and 2013, before declining more recently. As is, non-Hispanic white mothers will probably not become a minority of new moms until 2026. Falling birth rates postponed this minority-majority shift by six years.

This runs counter to common misconceptions about fertility and U.S. racial demography. Many people mistakenly believe that higher birth rates will delay America becoming a minority-majority country, but this is wrong. Because racial birth rates tend to converge towards each other over time while sharing similar cycles due to economic and other shocks, increases in birth rates tend to yield relatively more babies among minority moms. Moreover, because minority women make up a larger share of reproductive-age women compared to their share of the general population, fertility in general tends to cause a change in racial demography. On average, a baby is less likely to be white than a current adult, so having more babies tends to make the country more racially and ethnically diverse.

All of this matters because those of us who support the government doing more to help families achieve their fertility goals have sometimes been tarred as racist on that basis. But the reality is that higher birth rates would hasten the pace of racial and ethnic change in the United States rather than maintain a white majority.

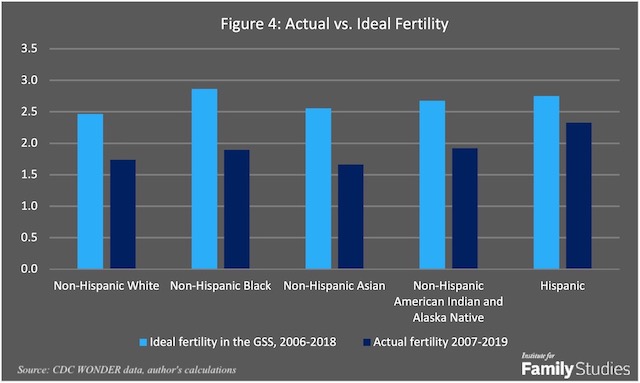

Indeed, if the government provided more support to families, such as expanding the child tax credit, birth rates would likely increase across all racial and ethnic groups. Since 2007, desired family size in various surveys has been fairly stable, and the average fertility rate for each ethnic group over this period was lower than the average “ideal number of children” reported to the General Social Survey in every case.

The loss of babies in the U.S. will have momentous consequences in the future, as the next generation is smaller than the one before it. The economic consequences of low fertility can be dire, as can other outcomes policymakers care about, ranging from military recruitment to instability in electoral coalitions. But these societal effects are of secondary importance to what low fertility means in the lives of those who experience “missing births,” ranging from rising loneliness to aging alone to less happiness. The consequences of low fertility today will echo through Americans’ increasingly empty homes for decades to come, leaving millions more people isolated and adrift from wider society as they age.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a market forecaster for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

*Photo credit: freestocks via Unsplash