Highlights

With the fiftieth anniversary of the Moynihan Report this year, there is renewed interest in the problems that are associated with single motherhood; most prominently, the behavior of fathers and its impact on children. Today, joblessness among prime-age black men is an even more serious problem than fifty years ago when Daniel Patrick Moynihan said it was at “disaster levels.” In 2014, only 70 percent of 25- to 34-year-old black men were employed, versus 83 percent of their white male peers. If we take into account the prison population and those who only work intermittently, almost half of black men in that age group do not have year-round, full-time employment. As in Moynihan’s day, high rates of joblessness lie at the roots of many social problems.

First, men’s lack of access to stable and well-paying jobs creates instability in romantic relationships. According to inner-city non-custodial fathers interviewed by Kathryn Edin and Timothy Nelson, mothers kick them out of the family home solely because of their lack of earnings. Inner-city single mothers, in contrast, blame men’s irresponsibility, infidelity, and violent behavior for breakups, as Edin and Maria Kefalas have documented. It is hardly surprising that men would neglect to mention infidelity and intimate partner violence to interviewers or that each sex would tend to blame the other for breakups. Yet men’s and women’s accounts may be more compatible than they sound: in recent years, at least, male joblessness is linked to higher rates of intimate partner violence, possibly because it engenders feelings of frustration and embarrassment.

Whatever the precise mechanism by which joblessness contributes to relationship turnover, the result is that a high share of black men and women have children with more than one partner—what Kathryn Edin has labeled “the family-go-round.” Almost 60 percent of black mothers with more than one child have children with at least two fathers, compared to less than 30 percent of comparable white mothers.

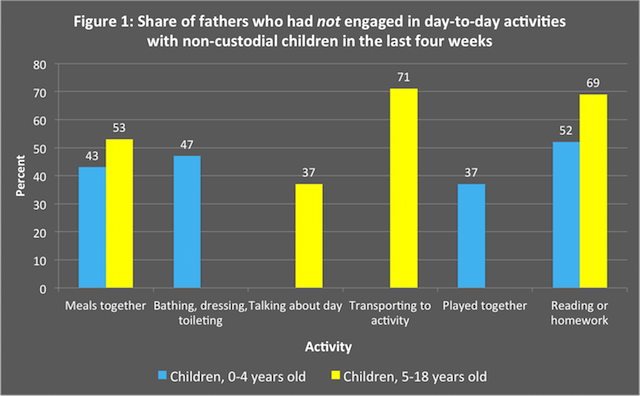

Relationship turnover and multi-partner fertility give rise to a multitude of problems for kids. Most obvious is the loss of contact with their fathers. Surveys show that a majority of fathers have limited involvement with their non-custodial children, especially after they and the mothers form new romantic relationships. In recent and past interviews, fathers profess remorse but blame it on external factors, particularly their joblessness, which robs them of the ability to buy their children presents and other provisions. Rather than face embarrassment, these fathers avoid their non-custodial children. Indeed, as the figure below illustrates, about half of fathers have not even eaten a meal with their non-custodial children in the past four weeks.

Source: Jo Jones and William Mosher, “Fathers’ Involvement with Their Children: United States, 2006-2010,” National Health Statistics 71 (Dec 20, 2013).

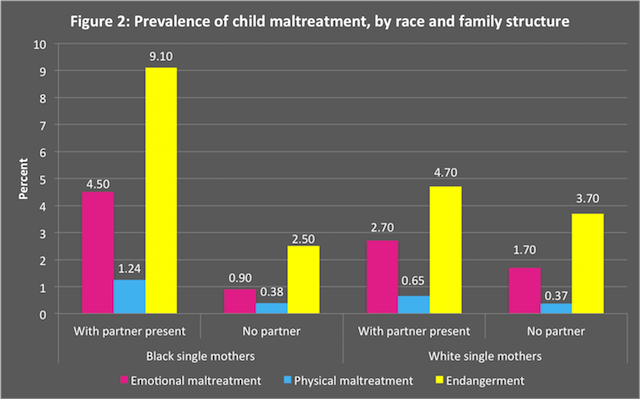

A minority of children suffer worse consequences from their parents’ unstable relationships: data show a dramatic increase in child maltreatment rates among single-mother households when there is a man present. In a just-completed study, Chun Wang and I find a strong link between joblessness and child maltreatment rates. Since black men are less apt to be employed than white men, these increases in maltreatment are particularly large among black single-parent households (see Figure 2).

Source: Andrea J. Sedlak, Karla McPherson, and Barnali Das, Supplementary Analyses of Race Differences in Child Maltreatment Rates in the NIS–4, Administration for Child and Families (Mar 2010).

Many studies document how family instability in general and multi-partner fertility in particular have adverse consequences on children, particularly boys. After adjusting for mothers’ race, education and employment, Cassandra Dorius and Karen Guzzo found that “Adolescents with a half-sibling with a different father are about 65 percent more likely to have used marijuana, uppers, inhalants, cocaine, crack, hallucinogens, sedatives, or other drugs by the time of their 15th birthday than those who have only full siblings.” Cynthia Harper and Sara McLanahan reported that among fatherless boys, those who lived with stepfathers were at an even greater risk of incarceration than those who lived with a single mother.

Suffering from a combination of parental joblessness, poverty, and an unstable and occasionally dangerous family environment, many black children enter high school with significant academic and behavioral deficits. Black secondary school students are more than three times as likely to be suspended as white students (24.3 versus 7.1 percent), for example. Behavioral and academic deficiencies translate into lower high school graduation rates: 52 percent of black men graduate, while 78 percent of white men do. In some areas the figures are even worse: In New York City and Philadelphia, only 28 percent of black males complete high school on time. Failure to finish school dramatically worsens young men’s job prospects, and so the cycle of family instability and its associated problems continues.

What can be done? We should not view black men as only victims of an uncaring if not racist system. We should not pretend that the disproportionately high suspensions rates are solely a function of implicit racial biases, or that black boys’ struggles in school are caused by a faulty education system. Instead, we must more honestly appraise and address the roots of these problems: joblessness. Of course, as policy-makers have discovered, creating good jobs for less-educated workers is easier said than done. Many policy advocates highlight College and Technical Education (CTE) programs that link high school coursework to community college occupational programs. While CTE programs can be effective, direct employment and short-term certificate programs are most helpful for a large share of the most at-risk students.

Certificate and narrow vocation programs are found primarily in for-profit schools, which have gotten an undeservedly bad rap because of the high failure rates and levels of indebtedness many students experience. Yet they do have strengths that other educational institutions lack: The education sociologist James Rosenbaum suggests “that many for-profits have developed good counseling departments that help students not only with their academic goals, but also with their economic and social problems.” In his words, “They put resources into counselors and they’re much better at retaining students than community colleges.” High schools should form partnerships with these best-practices for-profits. Given how valuable these links would be for the for-profits, high schools could negotiate very favorable conditions so that students could avoid high debt burdens while gaining valuable occupational skills.

By far the most important initiative for the most vulnerable students, however, would be private sector, year-round, part-time employment. These jobs enable youth to gain the personal discipline, interpersonal skills, and social connections that will be crucial to their future employment and personal relationships. Michael Gritton, executive director of the Workforce Investment Board, which promotes teen employment in Louisville, Ky., said, “There are economic returns to those young people because they get a chance to work. Almost every person you ask remembers their first job because they started to learn things from the world of work that they can’t learn in the classroom.” Sadly, the teen employment rate in 2013 was little more than half what it was fifteen years ago as firms shifted toward employing young adults and retirees. Nationally, only one in ten black teenagers from low-income households is employed.

High schools can initiate work-readiness programs that prepare students for the workforce. These efforts should be patterned after welfare-to-work efforts two decades ago. Just as in the welfare reform era, government should provide the support services and wage subsidies that will entice private-sector employers to hire these young men and women.

For many educators, the ideal is academic learning—meaning a four-year college education—for all. But disadvantaged youth, as well as their future romantic partners and children, may do better in the long run if we prioritize connecting them to the labor market.

Robert Cherry is Stern Professor in Economics at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.