Highlights

- The real housewives of America are most likely to be found among women married to men earning just a little or quite a lot. Post This

- Only 28% of American married mothers say full-time work is their ideal work situation, whereas 43% of married women without children say so, according to a new IFS/Wheatley Institution survey. Post This

Devotees of reality TV may think that stay-at-home moms are more common among the rich—think the “ Real Housewives” of Orange County, of Beverly Hills, of Atlanta, and so on. By contrast, close observers of American family life may think stay-at-home moms are more common among the poor.

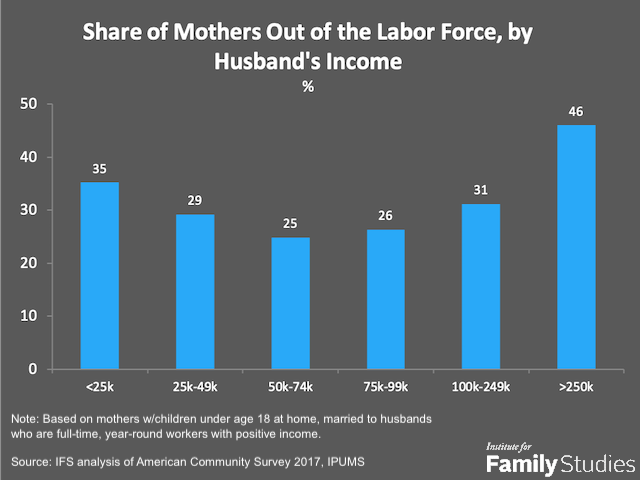

It turns out they are both right, according to a new Institute for Family Studies analysis of the 2017 American Community Survey. Among mothers married to husbands who work full-time and year-round—the population most likely to have the option of staying home—there is a U-shaped curve between a mother's chances of being out of the labor force and her husband's earned income. That is, the real housewives of America are most likely to be found among women married to men earning just a little or quite a lot.

Close to half of mothers whose husbands earn $250,000 or higher a year (46%) are not in the labor force. On the other end of the income spectrum, 35% of mothers whose husbands make less than $25,000 a year are stay-at-home moms. Mothers married to husbands with an income between $50,000 and $75,000—the group that includes the median husband’s income of $60,000—are the least likely to stay at home; only 25% of them are out of the labor force.

We’re not showing up at the “mommy wars” to support a certain side—VerBruggen is the son of a stay-at-home mom and the husband of a working one, so he’s not allowed to say anything judgmental about either arrangement, while Wang is a working mom who is sometimes envious of her stay-at-home friends. But when we noticed this pattern, we couldn’t resist exploring these data further, both to sort out the relationship between husbands’ income and wives’ working decisions and to see if it has changed in recent years, especially because breadwinner moms have become more common in today’s families.

So why would we see a U shape rather than a linear relationship between men’s income and women’s labor force participation? After all, economic theory might predict a simple rising line, because as one’s spouse makes more money, the returns to additional income diminish and thus staying at home becomes more attractive to at least some women.

A couple of factors are at play. First of all, people with similar educational and economic backgrounds tend to marry each other—a phenomenon known as “assortative mating.” Lower-income men often partner with women whose potential earned income is also lower. When children are in the picture, the high childcare costs often outweigh that (potential) second income. For these couples, it often makes more financial sense, given high childcare costs and her low potential earnings, to have someone stay at home, usually mom.

But on the other hand, higher-income men tend to marry women with higher education and higher earnings. For these mothers, opting out of the workforce carries a higher opportunity cost. Therefore, only when the husband’s income reaches a certain level, can the family start to “afford” to have these women stay at home.

Of course, we are only talking about raising children in economic terms here. Despite parenting being time-consuming and exhausting work, parents actually find the time they spend taking care of their children more rewarding than the time they spend at work, according to Wang’s earlier research using time-use data. Moreover, in an age of helicopter parenting, raising children often feels like more than a full-time job today. It is no surprise that some women may want to or feel like they need to trade their professional jobs for a full-time (unpaid) job at home.

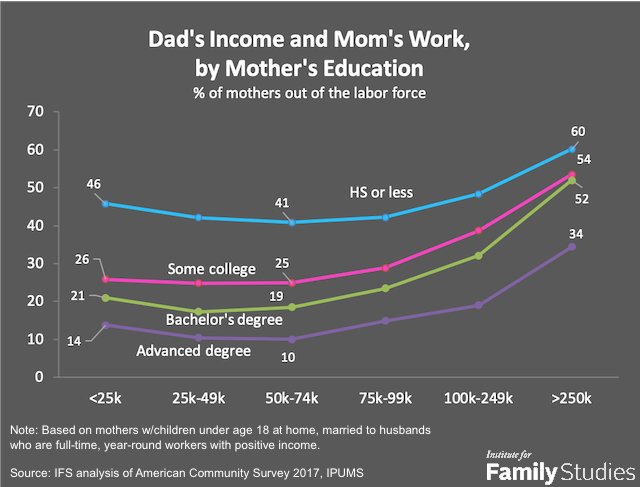

One way of testing this is to look at the impact of education on the married mothers in our sample because education is a rough proxy for earning capacity. And what makes this complicated is that it really is the case that higher-earning dads have higher-educated wives. The higher the father’s income, the more likely it is that the mother has a BA or more—above 75% when the father’s income tops $250,000. So, the education dynamic may straighten out the curve somewhat for more educated women.

We wouldn't expect to fully straighten out the curve by accounting for this, because assortative mating happens within educational categories as well. (For instance, Ivy League grads are disproportionately likely to marry other Ivy League grads, not just to marry college grads in general.) But we should expect the left-hand side of the shape to be less pronounced when women are separated by education.

Indeed, that is what we see. A 10-point drop in labor-force opting-out among married mothers in our initial chart is cut down by half or more within educational categories.1

This theory, then, is a good fit for the data and makes a great deal of intuitive sense. Further, our results are strikingly similar when the same analyses are run on the 2010 ACS instead of the 2017 ACS, suggesting that these patterns are reasonably stable over the short run. It appears there has been little change in the relationship between men’s income and women’s moves to stay at home among married parents over the course of the last seven years.

To be sure, there is a difference between a commonsensical theory consistent with the facts and an ironclad causal inference. There are other ways to interpret these findings, some of which are probably another part of the story and deserve further exploration. There may be a selection effect in which higher-earning men seek out women willing to stay home, for example, or differences in values among women of different skill levels. In previous work, Wang found that lower-income women are more likely to say their ideal arrangement would be to work full time.

Further, while education is a proxy for earning capacity, it’s also an indication of a woman’s intention to work; a college education is, after all, largely an investment in one’s future ability to make money.

And as it happens, a new survey conducted by IFS and the Wheatley Institution sheds even more light on the factors related to women’s labor-force participation.

The “Ideal” Work Situation for Mothers

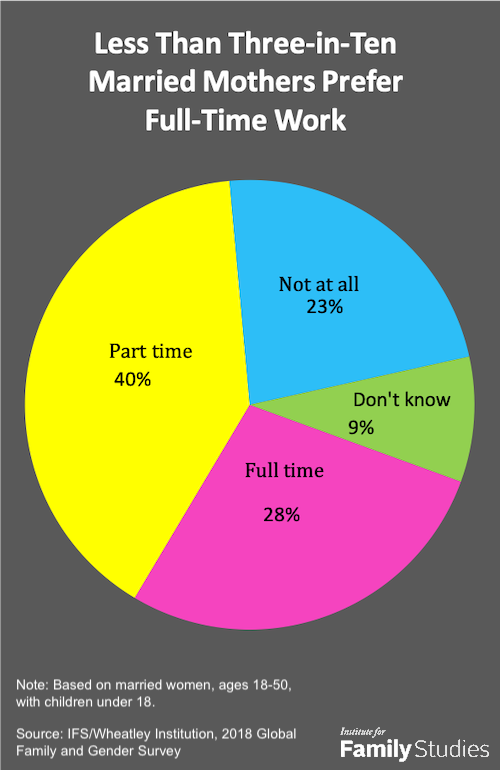

Having children is a major life-changing event for both men and women. And priorities in life can also change because of parenthood. When asked what their ideal work situation would be, only 28% of American married mothers say it is full-time work, whereas 43% of married women without children say so, according to our new survey.2

Meanwhile, 40% of married mothers consider working part-time to be their ideal situation, which makes part-time work the most popular choice. And more than one-in-five married mothers prefer not to work for pay at all. (The rest, 9% of married mothers, haven’t made up their mind yet.)

Children’s age also plays a role in mothers’ preferences. Among married mothers with children ages 0 to 3 at home, only 17% prefer to work full time, and 34% consider staying at home as their ideal situation. In contrast, 31% of married mothers with children ages 4 to 17 prefer full-time work, and 21% prefer not to work outside the home. The share of married mothers who prefer part-time work is around 40%, regardless of their children’s age.

Overall, mothers are more likely than non-mothers to express a stronger desire to either work part time or not at all, regardless of their marital status. Findings from the new IFS/Wheatley Institution survey suggest that 37% of mothers with children under age 18 prefer part-time work, and 21% prefer not to work outside the home at all (32% prefer full-time work). And among women without children under age 18, only 28% prefer to work part time, 10% prefer not to work, and 51% consider full-time work their ideal.

Given that the survey was conducted online and allowed respondents to report “don’t know” in their responses, the results are not directly comparable to those of previous telephone-based surveys on the same topic. Nevertheless, they are broadly consistent with what previous surveys found. For example, in a 2012 Pew Research Center telephone-based survey, 53% of married mothers said that part-time work was ideal and 23% preferred not working for pay at all.

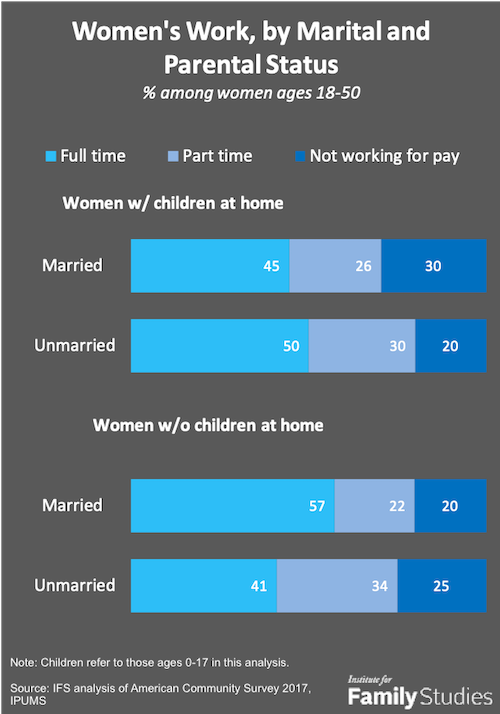

It is important to note that the “ideal” situation does not always align with reality. Despite a strong preference for part-time work, only 26% of married mothers ages 18-50 work part-time, according to our analyses of the 2017 American Community Survey. In contrast, 45% of married mothers work full-time, and 30% do not work for pay.

Marriage just by itself today does not seem to have an impact on women’s labor-force participation. In fact, among women without children under age 18 at home, married women are more likely than unmarried women to work full-time. This could be because highly-educated women today are more likely than their less-educated peers to marry, and also more likely to work full time.

However, parenthood still matters. Married mothers are more likely to be out of the labor force than other women. For women ages 18-50, the group most likely to not be working is married mothers (30%).

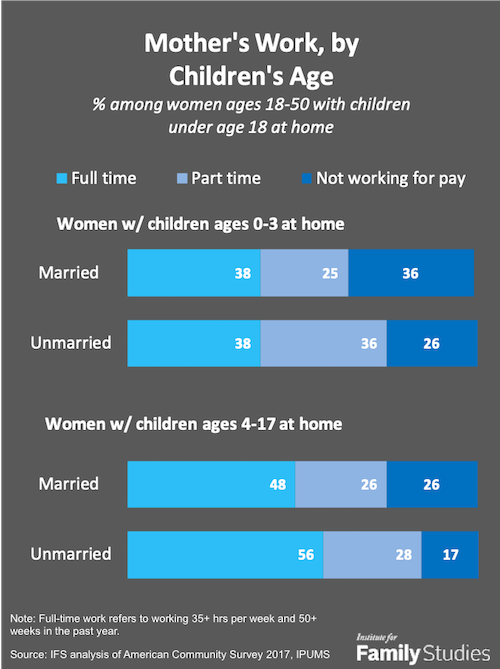

On the other hand, a mother's work status differs sharply by her children’s ages. Only 38% of mothers with infants and toddlers work full time, regardless of their marital status. And 36% of married mothers with children ages 0 to 3 do not work outside the home. The share among unmarried mothers with children at this age is somewhat lower (26%).

Mothers are much more likely to work full-time when their children are older. Close to half of married mothers with children ages 4 to 17 at home (48%) work full time, and a majority of unmarried mothers with children of similar ages work full time (56%).

It is not surprising to see that mothers of children ages 0 to 3 are the group who are most likely to stay at home. Children at this age demand an enormous amount of parental care, and it is very expensive to outsource this job. The annual child-care cost for a young child now exceeds $12,000, on par with college tuition, in many states in America. Given current costs, for many parents (not only mothers), staying at home makes more economic sense.

In the end, what we see in the data is that different families divide work and family responsibilities in different ways—sometimes because of how much money a spouse is bringing in, sometimes because of the cost of child care, and sometimes simply because different people value different things. But what this research brief tells us is that her education, his income, and their child’s age all loom large in shaping who does what in contemporary American married families.

Robert VerBruggen is a Research Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and deputy managing editor of National Review. Wendy Wang, Ph.D., is Director of Research of the Institute for Family Studies and the lead author of Breadwinner Moms(Washington, DC: Pew, 2013). Download a copy of this research brief here.

1. A logistic regression predicting the labor-force participation of the wives in our sample is consistent with this story as well. When the women’s race, nativity, and age are controlled, along with a dummy variable indicating whether any children are under age 5, paternal incomes are positively correlated with being out of the labor force, while higher levels of maternal education are negatively correlated.

2. The survey was conducted on Sep 13-25, 2018, with a nationally representative sample of 2,025 adults ages 18-50 in the U.S. via the Knowledge Panel of Ipsos. It is part of the IFS/Wheatley Institution 2018 Global Family & Gender Survey (GFGS).