Highlights

- Yes, higher masculinity is associated with men reporting more aggression, loving a good fight, and even taking advantage of others, as well as general assertiveness like taking charge. Post This

- At the same time, men higher in feelings of masculinity also report more stable and resourced life outcomes, including higher income and education, a healthier weight, greater religiosity, and increased general happiness and life satisfaction. Post This

- Very masculine men are also the most likely to marry and to report feeling loved in their marriages, per a national survey. Post This

The problem with men is real. Men commit nearly nine out of 10 murders and are responsible for 72% of criminal arrests. They take their own lives at 3.6 times the rate of women. And their prospects for the future can be bleak—men are more likely than women not to have the support of close friends, and today’s young man is less likely to attend and graduate college than his female peers.

If you think the reason that some men are so troubled is that they are plagued with masculinity, you are not alone. Even the American Psychological Association (APA) says so:

[T]raditional masculinity—marked by stoicism, competitiveness, dominance and aggression—is, on the whole, harmful. Men socialized in this way are less likely to engage in healthy behaviors.

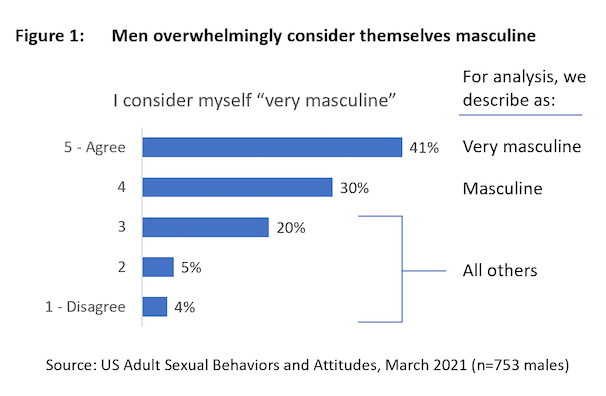

Recent data collected in the March 2021 U.S. Adult Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes survey lets us explore the supposed masculinity problem. In that survey, 753 men were asked if they considered themselves very masculine on a 5-point scale.1 Fully 41% of men agree that they are very masculine, or checked 5 on that scale, and another 30% consider themselves masculine, or checked 4 on that same scale. And when asked if they are happy with how masculine or feminine they are, 80% of men further reported being happy (not shown).

If masculinity is a problem, then it would seem we are in big trouble given how many men gladly consider themselves masculine. But can we show that it is really a problem? To find out, we analyzed men in three groups—very masculine, masculine, and all others—to help us better understand what masculinity is all about.

Let’s tackle the accusations head on. Yes, higher masculinity is associated with men reporting more aggression, loving a good fight, and even taking advantage of others, as well as with general assertiveness like taking charge (see Figure 2).2 Stop there, and there is support for the idea that the world would be a better place—and men would be better men—if we followed the lead of mainstream media and many large advertisers in shaming the masculinity out of manhood.

But masculinity doesn’t stop there. In fact, when we look at these findings in the full light of data, it’s clear that instead of shaming masculinity out of modern manhood, it might be better to support and strongly encourage men’s daily experiences of their masculinity—both feeling masculine and being happy about it—because masculinity lies at the heart of productive, contributive manhood.

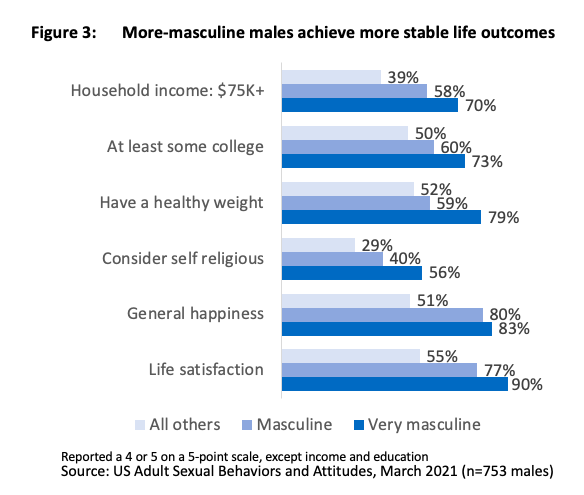

First, men higher in feelings of masculinity also report more stable and resourced life outcomes, including higher income and education, a healthier weight, greater religiosity, and increased general happiness and life satisfaction, as shown in Figure 3.

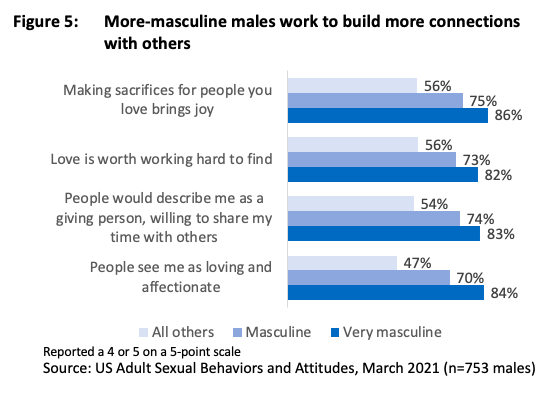

But what about the ability of these men to have healthy, nurturing relationships—which is clearly a problem for masculine men, right? Not so fast. In fact, this survey shows that very masculine men are also the most likely to marry and to report feeling loved in their marriages. Unlike the image often presented in our culture, these very masculine men are more likely to seek emotional closeness and friendship with their ideal partners—and are the most likely to report being always faithful to their sexual partners.

It’s likely that these stable personal and intimate life outcomes are the result of these men’s hard work and efforts to provide for and take care of those around them. These very masculine men are also most likely to say that making sacrifices for loved ones brings joy, to agree that love is worth working hard to find, and to believe that others see them as giving, sharing, loving, and affectionate.

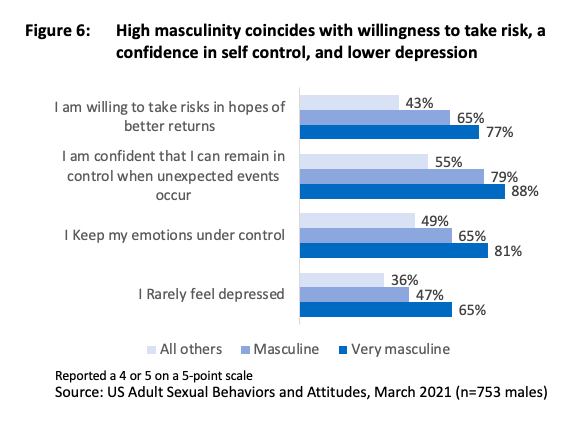

How do they achieve these relationships among other outcomes? By taking risks and exercising self control, all of which corresponds with a lower propensity for depression (see Figure 6).

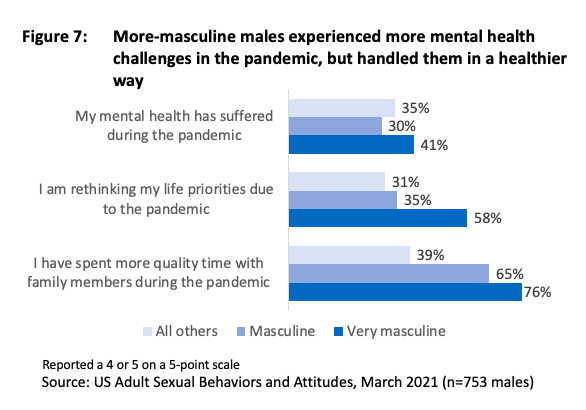

This is not merely theoretical. During the pandemic, as many have struggled to adapt, very masculine men were not exempt. Counter to stereotypes, these men reported as much or more mental health difficulties during the pandemic than average men (see Figure 7). But they also expressed a willingness to put in the work to address these challenges, reporting spending more quality time with their family and being willing to rethink life priorities due to the pandemic.

The truth about masculinity is inescapable, according to these survey results. Far from being a problem, it brings with it exactly what individuals, couples, families, and communities seek, perhaps especially in challenging times. As we’ve seen here, an internal sense of masculinity corresponds with men’s ability to be functional, stable, contributing members of their communities. It’s a good thing so many men are comfortable and happy with being very masculine. As a society, we would be wise to accept the positive power of masculinity and continue to channel its energy into productive outcomes.

James L. McQuivey (Ph.D., Syracuse University) has taught at Boston University and Syracuse University. He is a consumer behaviorist and analyst who is regularly sought for commentary by publications like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. His research into family studies focuses on human mating strategies and the role of parents in determining positive life outcomes. He is the author of the book Why We Need Dad.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. The survey of U.S. Adult Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes was fielded to a U.S. representative sample of adults ranging in age from 18 to 74 in March 2021 (n=1567). The outgoing sample was balanced by sex, age cohort, and U.S. Census region. Sample sourced from and data collection provided by Dynata, a global leader in first-party data and data services. The respondents were weighted back to the outgoing sample parameters for sex, age, marital status and region. Data were validated for internal consistency and compared for population representation to US Census data and GSS data for income, rates of marriage, and childbearing. The project was conceived, designed, executed, and majority funded by Dr. James McQuivey.

2. With the exception of income, education, and marital status, all data here are collected on five-point scales and correlate by at least the .05 level or lower of statistical significance when correlated with the five-point scale of self-perceived masculinity. Income, education, and marital status were all tested for significance using proportions testing (z-scores) with differences reported also significant at the .05 level.