Highlights

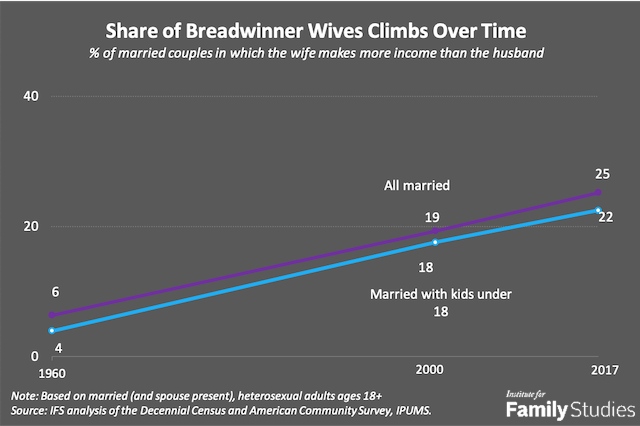

More women are family breadwinners today. New data from the American Community Survey suggest that among married, heterosexual couples in the U.S., a quarter of wives, or about 15 million, are the primary breadwinners in their family. In 1960, the share was only 6%. Moreover, in 22% of married households with young children under age 18, mothers are the primary breadwinners.

Women’s progress in the workplace and their economic contributions to their households should be applauded, yet female breadwinners seem to face a “happiness penalty” compared to women who earn less than their husbands.

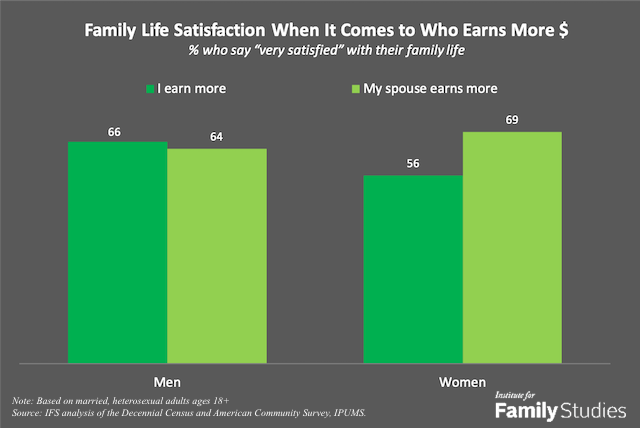

When it comes to family-life satisfaction, women who earn more than their husbands report lower satisfaction than their peers who have a lower income than their spouses, according to a new Institute for Family Studies/Wheatley Institution survey of U.S. adults ages 18 to 50. Just over half of women who out-earn their husbands (56%) say they are very satisfied with their family life, compared with nearly 70% of women who are not the primary breadwinner in the house. In contrast, the survey suggests that life satisfaction does not differ significantly among married men, whether they are the primary breadwinner or not.1

On other measures, including marital satisfaction and whether the couple feels close and engaged in the relationship, female breadwinners also score lower than their peers who earn less than their husbands. And again, these differences are not observed among married men.

The culprit here may be traditional gender norms. The idea that men should take the lead in breadwinning and women in caring for children and the home still affects men and women today, and a violation of this norm could make some couples uncomfortable with their arrangement. A good example is that when wives earn more than their husbands, both spouses misreport their actual income in surveys. Women under-report their income and men overreport it. The norm that men should be the lead breadwinner still has a strong hold on our society.

However, this theory does not explain why only women appear to be affected by this departure from traditional gender norms. Perhaps women are more likely to hold traditional gender norms than men and therefore are more uncomfortable about their new role as breadwinners?

In fact, married women are no more likely than men to hold traditional views of gender norms. In the IFS/Wheatley survey, about 48% of married men agree that “it is usually better for everyone involved if the father takes the lead in working outside the home and the mother takes the lead in caring for the home and family,” while only 43% of married women agree with this statement.

To understand this puzzle, we need to look beyond earnings and look more into the day-to-day family life of couples.

A recent study suggests that how couples divide their household tasks is linked to their relationship satisfaction. And an earlier Pew Research survey found that “sharing household chores” is ranked as one of the top three factors associated with a successful marriage. In the public’s eyes, it is even more important than “adequate income” when it comes to a successful marriage.

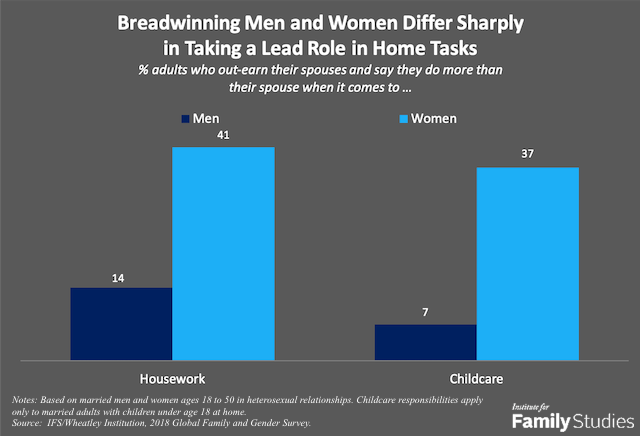

So how are typical household tasks divided when a wife earns more money than her husband? As it turns out, when the wife is the primary breadwinner, a plurality of women (41%) still take a lead role in housework. However, when the husband is the primary breadwinner, only 14% do more housework than their wives.

Meanwhile, just 17% of female breadwinners say their husbands do more housework, and 41% say they share household chores equally (results not shown in the figure). In contrast, more than a third of male breadwinners (37%) say their wives do more housework and 48% say these tasks are shared equally.

When it comes to childcare responsibilities, married mothers who are the primary breadwinner in the house are also much more likely than fathers in the same role to take a lead in the childcare responsibilities (37% vs. 7%). So, when wives are the primary breadwinners, they are still much more likely to assume a disproportionate share of housework and childcare. This is an example of the classic “second shift” that sociologist Arlie Hochschild pointed to in her book. It is easy to see why these overworked breadwinner wives and mothers may not be as happy as others.

Of course, in general, married fathers devote about as much overall time to work and family as married mothers. That’s because, while fathers as a group today still spend significantly less time on housework and childcare than mothers, they also spend more time overall in paid work, which balances out the total workload that fathers and mothers have.

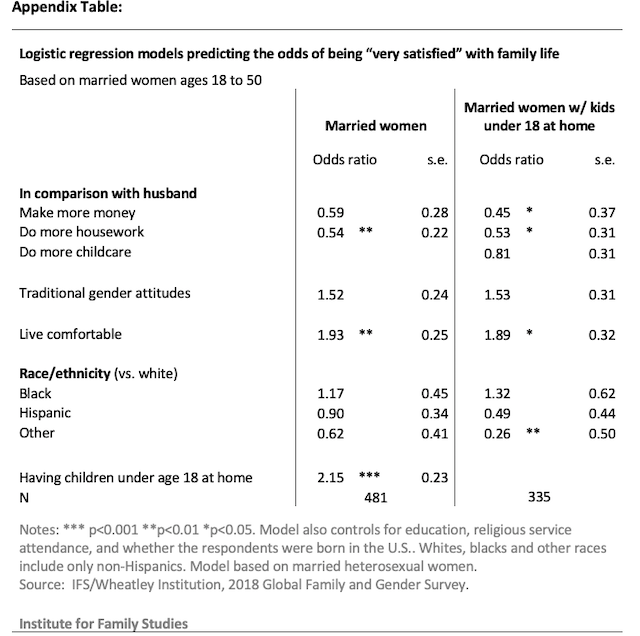

Since many factors can relate to how people feel about their family life, I explored bivariate and multivariate regression models to test whether the association between breadwinning, household division of labor, and family life satisfaction for married women (and mothers) is significant after controlling for other relevant factors. These factors include the family’s financial situation, beliefs about traditional gender roles, and church/religious service attendance.2 I also ran the multivariate models separately for married women in general and those with children under age 18 at home (see Appendix table at the end of this brief).

At the bivariate level, breadwinner wives are less satisfied with their family lives than wives who are not the primary breadwinners. Nevertheless, after controlling for other factors, the negative association between the breadwinner role and family life satisfaction is no longer significant for married women overall but is still significant among married mothers. Breadwinner moms are 55% less likely to be very satisfied with their family life than mothers who are not the primary breadwinner, even after controlling for the household division of labor, family financial status, gender ideology, and an array of other background variables.

On the other hand, the connection between the division of housework and family life satisfaction is significant for both married women and married mothers. Doing more housework than their spouse is linked to a lower level of life satisfaction for all married women after controlling for relevant factors. But for mothers, doing more childcare than their spouses is not significantly linked to family life satisfaction.

At a time when more women are family breadwinners, perhaps it is time for husbands to step up and take on more responsibilities on the home front.

In sum, findings from the multivariate analyses indicate that that the link between breadwinning and family life satisfaction is more pronounced among married women with children at home. This could reflect the fact that caring for children requires a lot more time and effort on top of regular housework tasks. And when a mother is also the family’s primary breadwinner, the unbalanced workload can take a toll on her family life satisfaction. At a time when more women are family breadwinners, perhaps it is time for husbands to step up and take on more responsibilities on the home front.

The Demographics of Breadwinning Women

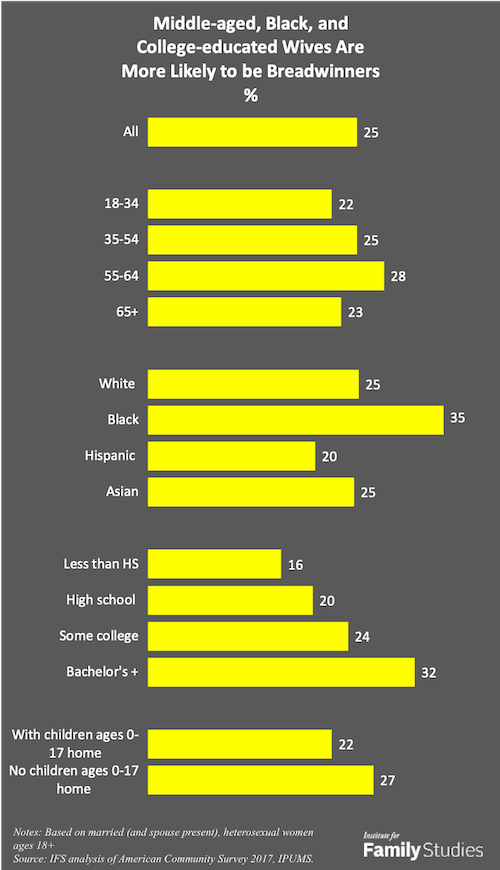

Although there has been a lot of buzz around young women making more economic gains relative to young men, Millennial women are NOT the group who are most likely to out-earn their husbands. Close to 3-in-10 married women in their mid-50s to mid-60s (28%) make more money than their spouses, compared with 22% of younger married women (under age 35) and 25% of married women ages 35 to 54, according to estimates based on the Census data.

Women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds also differ in their chances of being the primary breadwinner in the household. More than one-third of married black women (35%) out-earn their husbands. The share among white or Asian women is 10 percentage points lower, and the share among Hispanic women is the lowest (20%).

Finally, women’s educational achievement is positively linked to their chances of being the primary breadwinner. Among married women who have at least a bachelors’ degree, 32% earn more money than their husbands. In contrast, only 16% of married women with less than a high school education have a higher income than their husbands.

Another noteworthy characteristic of female breadwinning has to do with their family financial status. According to my analysis of the Census data, the median total family income of married women who out-earn their husbands was close to $90,000 in 2017, slightly higher than the median family income for married couples with a male breadwinner (about $88,000).

Couples are more likely to both work for pay in households where the wife is the primary breadwinner. This is probably why female-breadwinner households have a higher total income than male-breadwinner households. According to 2017 American Community survey data, the share of dual-earner couples was 55% among married couples where the wife is the primary breadwinner and 45% among couples where the husband is the primary breadwinner.3

Apparently, the slight income boost among female-breadwinner households is not enough to compensate these women’s lower levels of family life satisfaction. This echoes the previous Pew Research survey finding that sharing household chores trumps money when it comes to a successful marriage.

Wendy Wang, Ph.D., is Director of Research of the Institute for Family Studies and the lead author of Breadwinner Moms(Washington, DC: Pew, 2013).

1. The survey was conducted on Sep 13-25, 2018, with a nationally representative sample of 2,025 adults ages 18-50 in the U.S. via the Knowledge Panel of Ipsos. It is part of the IFS/Wheatley Institution 2018 Global Family and Gender Survey. Respondents were asked whether they earn more money than their spouse, their spouse earn more, or they earn about the same. Analyses in this report are based on married heterosexual adults. Results for married men and women who make about the equal amount of the money as their spouses are not shown because of the small sample sizes.

2. Models also include respondents’ education, race/ethnicity, and immigration status. Models are based on married adults ages 18 to 50 in heterosexual relationships. The number of valid cases in final regression models was 481 for married women and 335 for married mothers. See Appendix table for more details.

3. Among a small share of couples (3%), husband and wife make the equal amount of money. The share of dual-earner couples is nearly 60% among these couples, but their family income is relatively lower: 70,000 a year.