Highlights

- Between the 2013-15 NSFG wave and the 2022-23 wave, all measures of sexlessness rose for both young adult males and females. Post This

- Married people have more sex, and for most young adults, marriage is occurring later or not at all. Post This

- The major decline is in sex between people who only had sex with one person in the prior year, i.e. approximately monogamous sex. Post This

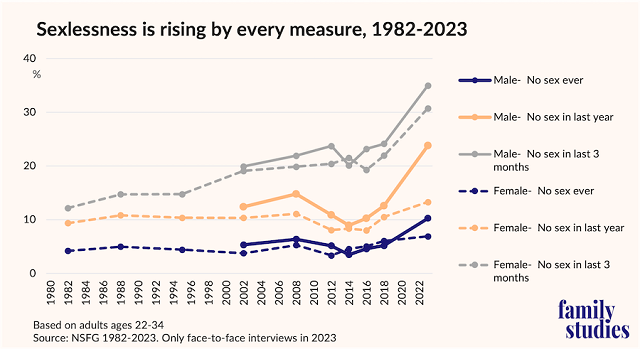

Americans are having less sex. At IFS, we’ve written about this many times before, covering different aspects of this trend, but newly-released data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a periodic survey of sexual and family behavior, drives this point home. Sexlessness skyrocketed between 2017-19 (the last wave) and 2022-23 (the most recent survey wave). The figure below shows the share of men and women ages 22-34 who: a) had never had sex or, b) had not had sex in the last year, or c) had not had sex in the last 3 months.1

We focus here on males and females ages 22-34 because this is the key window in which people tend to marry and start families, and to avoid the thorny question of teen sex: it might be a good thing if 17-year-olds are having less sex! But by focusing on young adults 22-34, we are talking firmly about adults, most of whom have completed education and are setting out on independent lives. Furthermore, the 2022-23 NSFG wave included a new online survey component, which returned unusually high rates of reported sexlessness. For comparability, we limit our results for 2022-2023 to results from the face-to-face interviews, most of which occurred in 2023.

Between the 2013-15 NSFG wave and the 2022-23 wave, all measures of sexlessness rose for both young adult males and females. In terms of virginity, young adult males rose from 4% virgins in 2013-15 to 10% in 2022-23; for young adult females, reported virginity rose from 5% in 2013-15 to 7% in 2022-23.

But a larger share of young adults have had sex at some point—just not in the last year. Sexlessness in the last year rose from 9% for males in 2013-15 to 24% in 2022-23. For females, it rose from 8% to 13 percent.

And finally, we can ask what share of respondents hadn’t had sex in the last 3 months, a decent measure of the share who aren’t in a sexual relationship at a given time. This share rose from 20% for males in 2013-15 to 35% in 2022-23, and from 21% to 31% for females.

In sum, for young adult males, sexlessness has roughly doubled across all measures over the last 10 years or so. For young adult females, it has risen by roughly 50 percent.

It should be noted that most of this increase occurred between 2017-19 and 2022-23. This could reflect some kind of methodological change in the NSFG, the effects of COVID disrupting relationships, or something else, though, as noted, we excluded the biggest method change, the addition of an online survey mode.

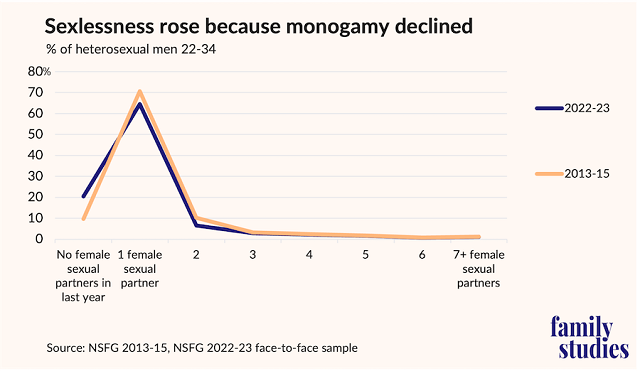

The fact that sexlessness is rising faster for men than for women could seem to imply that a small group of men are having sex with many women. This isn’t the case. The figure below compares men in 2013-15 to 2022-23.

There was a rise in the share of heterosexual males with no female sexual partners in the last year—but it was driven mostly by a decline in the number of males with one female partner, and secondarily by a decline in the number of men with two. There was no change at all in the prevalence of heterosexual men with large numbers of female sexual partners. Thus, what we can actually observe is not that a small number of men are having sex with more and more women, but simply that men and women are failing to couple off together: the major decline is in sex between people who only had sex with one person in the prior year, i.e. approximately monogamous sex.

This is because one of the biggest drivers of declining sexual activity is the decline in marriage. Married people have more sex, and for most young adults, marriage is occurring later or not at all. As a result, sex is declining.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.

1. From the 2011-2013 wave onwards, “sex” is defined as the respondent reporting any kind of intercourse with another person of any sex, and thus includes non-vaginal sex and same-sex activity. Before 2011-2013, same-sex sexual activity is not fully included, and some non-vaginal opposite-sex activity may not be fully included. As such, the apparent “decline” in sexlessness between the 2006-2010 wave (the point at 2008) and the 2011-2013 wave (the point at 2012) is at least partly a statistical illusion due to the 2011-2013 and later waves having a broader definition of sexual activity and thus lower rates of sexlessness.