Highlights

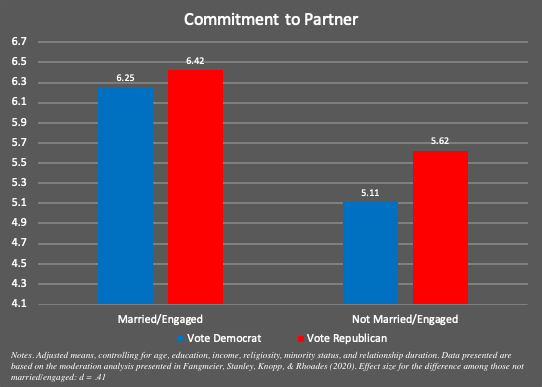

- Commitment levels of married and engaged Republicans and Democrats were similar, but unmarried Democrats were less committed, on average, than their unmarried Republican counterparts. Post This

- On average, we found no difference in relationship adjustment or commitment based on whether one was in a relationship with someone voting similarly or differently. Post This

- In our study, we found no statistically significant difference between Democrat, Republican, or Independent voters in overall ratings of relationship adjustment. But there was a difference in average ratings of relationship commitment. Post This

Nothing escapes intersection with politics during these partisan times. How do relationships where two partners have strong political differences compare to others with regard to relationship quality and commitment? Are there broad differences in relationship quality for those typically voting Democrat, Republican, or Independent?

In a newly published study, we, along with our colleagues (Galena Rhoades and Kayla Knopp), address both of these questions.

The study’s context is important to keep in mind as we consider the findings. We analyzed data from the last time point (11) of a 5-year, longitudinal sample. At the time of recruitment, individuals were between the ages of 18 and 34, and unmarried but in serious romantic relationships.1 We only analyzed one time point because that is the only time where people were asked “How do you usually vote?” and “How does your partner usually vote?” For this new study, we examined overall relationship adjustment and overall commitment to one’s partner. In every analysis, we controlled for age, income, education, minority status, relationship duration, and religiosity. These responses were gathered during 2012, when Barack Obama and Mitt Romney contested for the presidency. Many perceived that as a contentious election cycle. How naïve of us all. Thus, the context for our findings was a partisan election year, but perhaps not to the degree we see today.

It is also important to note that by wave 11 of the underlying project, half of the sample was married and most all of the respondents were in a serious, committed, romantic relationship (of average duration of 5 years). Thus, the sample was of committed relationships but not long-term married couples.

Do Opposites Attract or Repel?

The impact of voting dissimilarity on romantic relationships has been the subject of numerous articles, such as here, here, here, and here. Most people, however, are married to or living with a partner of similar political leanings. Indeed, a recent Pew Survey put the estimate of married and cohabiting couples with politically similar partners at 77 percent.

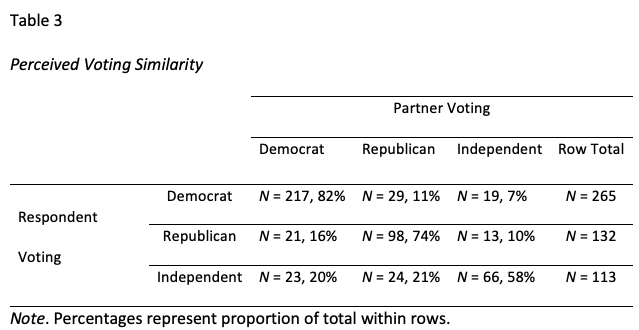

In our sample, 52.0% usually vote Democrat, 25.9% Republican, and 22.2% Independent, with 75% reporting voting similarity. Democrats were most likely to report being with someone voting the same way, followed by Republicans and Independents.

Source: Fangmeier, Stanley, Knopp, & Rhoades (2020).

Although some people actively seek partners who are politically similar, evidence suggests most people end up with someone sharing similar views because most people marry within their social circle and among those with similar demographics.2 It would not be surprising if that is changing. Increased mobility and internet dating may make it increasingly likely that a person will fall in love with someone who does not share his or her political views.

There is evidence that people shift toward liking a potential partner less when they discover political differences.3 Further, an article by Kevin Enochs for Voice of America drew contrasts based on the research of Lynn Vavreck, suggesting there has been a large shift toward parents finding it unacceptable for their child to marry someone of another party. Fitting nearly anyone’s intuition, a study by Afifi and colleagues found higher stress and conflict in relationships where partners voted differently in the 2016 presidential election. Overall, there is some evidence that opposites repel, but modestly.

Does that mean voting differences between partners are commonly associated with relationship struggles? In our new study, we found no difference, on average, in relationship adjustment or commitment based on whether one was in a relationship with someone voting similarly or differently (with a possible important exception noted below). This is a potentially important finding, given the paucity of published research on the subject.

It is also good news. Most people, at least in the the stage of life we studied, were not struggling with relationship difficulties based on partisan differences. Further, while Afifi and colleagues reported that relationships where people had voted differently in 2016 were more prone to struggle, they also found that those who were regularly working on their relationship faired best. It is reassuring to know that even where political differences exist, they can be overcome in the same way two partners overcome any differences—with respect, skill, and commitment.

Party and Relationship Quality

What is the association between relationship quality and political party preferences (if any exists)? There has been little published research on this question; however, a variety of reports have suggested those with more conservative political tendencies tend to have a consistent edge, on average, in marital or relationship quality. In the U.S., whether one tends to vote Republican or Democrat is a proxy for conservative or liberal leanings. Although unpublished in journal articles, findings on this subject have reported the following, based on large, representative samples in the U.S.:

- Wilcox and Wolfinger (2015) used the U.S. General Social Survey (GSS: 2010-2014) to study marital happiness and found Republicans reported higher average ratings than Democrats. A substantial part of this association was explained by other differences, such as race and religious involvement, but the difference remained even when controlling for such factors.

- Wolfinger (2017) also used the GSS and found that married Republicans tended to report greater sexual satisfaction and lower rates of infidelity than Democrats.

- Karpowitz and Pope (2018) fielded a large-sample survey in the U.S. focused on marriage and family. They found Republicans were less likely than Democrats or Independents to report, at some point in the past two years, they had thought their marriage was in trouble.

There is an obvious consistency to these findings. Indeed, anywhere we found survey findings on relationship related differences between Republicans and Democrats (or liberals and conservatives), the results always tilted the same way, even if findings weakened when controlling for obvious demographic differences between groups.

In our study, we found no statistically significant difference between those voting Democrat, Republican, or Independent in overall ratings of relationship adjustment. However, there was a difference in average ratings of commitment to one’s partner, with Republicans reporting higher levels of commitment than Democrats. Further, being in a relationship with someone perceived to be voting Democrat was also associated with lower commitment to one’s partner.

Importantly, the findings on commitment were moderated by commitment status, essentially driven by unmarried respondents. We found that the commitment levels of married and engaged Republicans and Democrats were similar, but unmarried Democrats were less committed, on average, to their partners than their unmarried Republican counterparts, as depicted in this chart.

Additionally, those partnered with Democrats reported lower relationship adjustment than those partnered with Republicans, regardless of marital status. The difference in relationship adjustment based on a perception of the partner’s voting may seem odd in light of the non-significant difference on relationship adjustment for how respondents personally voted. However, that latter finding was in the same direction, albeit not quite at a level reaching statistical significance.

An exploratory finding in our examination of voting similarity might explain these findings suggesting that those partnered with a Democrat experience lower relationship adjustment. Specifically, in more targeted analyses, we found that those voting Republican reported substantially lower relationship adjustment if partnered with a Democrat. We did not find statistically significant differences with any other pairing. These analyses should be considered tentative because, once you get down into specific matches, and especially this one, the sample becomes quite small. In other words, this specific finding may or may not replicate, but it presents an intriguing question to explore further. Broadly, our findings are consistent with those from numerous prior reports from various types of surveys, while adding to the literature and suggesting avenues of further exploration.

What about the findings regarding commitment? Although Republicans, on average, may be more highly committed to their partners before or outside of marriage, “Democrats may be less likely to marry because they are less committed to their partners in unmarried relationships, or they may be less committed to partners they are unlikely to marry,” as we put it in the paper. Additionally, there could be a group of Democrats who are generally less committed to both marriage and a long-term future with a partner, and they may account for this overall difference in groups among those not married or engaged.

None of these findings are particularly surprising given what we already know about differences among Democrats and Republicans. We know that Democrats are less likely to be married than Republicans, and marriage is a strong proxy for commitment between partners. Although we controlled for various socio-demographic differences, including religiosity, there may be many deeper cultural differences at work behind our findings as well as those found by others.

Differences in commitment might also be explained by the work of Jonathan Haidt and colleagues on Moral Foundations Theory. In simple terms, their work suggests the dimensions of care, fairness, liberty, loyalty, authority, and sanctity underly moral foundations within people. Following the election of 2004, they examined this theory in relation to political identification, consistently finding that Democrats tended to be most animated by care, fairness, and liberty, while Republicans were more evenly moved by all six dimensions, and reported much more connection to loyalty, authority, and sanctity. While it may be a stretch, what they described as differences in moral foundations could partly underly the findings on commitment in our study. Perhaps all three of the latter moral dimensions provide stronger support for commitment to one’s partner in or outside of marriage.

You cannot know how good someone’s relationship is by knowing how that person votes. But, as our research and the research of others confirms, political leanings can be associated with other aspects of relationships and life. How could it be otherwise? There is one thing we know for sure. This is a subject with surprisingly little research, and much more could be explored. We would vote for that.

Scott M. Stanley is a research professor at the University of Denver and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies (@DecideOrSlide). Troy L. Fangmeier is a graduate of the University of Denver and has worked with Scott Stanley and Galena Rhoades on relationship research for 6 years.

1. The original sample development is described in: Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2010). "Should I stay or should I go? Predicting dating relationship stability from four aspects of commitment," Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 543-550.

2. Coffé, H., & Need, A. (2010). "Similarity in husbands and wives party family preference in the Netherlands." Electoral Studies, 29(2), 259-268.

3. Mallinas, S., Crawford, J., & Cole, S. (2018). "Political opposites do not attract: The effects of ideological dissimilarity on impression formation." Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 6, 49-75. Easton, M. J., & Holbein, J. B. (2020). "The democracy of dating: How political affiliations shape relationship formation." Journal of Experimental Political Science. Advance online publications.