Highlights

Blue families are stronger and more stable than red families. Until recently, this was the conventional wisdom in the media and the academy. But this belief has been challenged by new reports in Family Studies and the New York Times. At least at the regional level, blue families—that is, families in areas that vote Democratic in presidential elections—do not have an advantage. It turns out that, on average, more conservative counties across the country have more marriage, less nonmarital childbearing, and more family stability for their children than do more liberal counties.

Some scholars haven’t been persuaded by the new research. For instance, economist Noah Smith, who has argued that “liberal morality is simply better adapted for creating stable two-parent families in a post-industrialized world,” wondered if the new red families vs. blue families story held up at the family level: in his words, “Try doing family-level studies” of the red vs. blue divide. We have taken up Smith’s challenge in this Institute for Family Studies research brief.

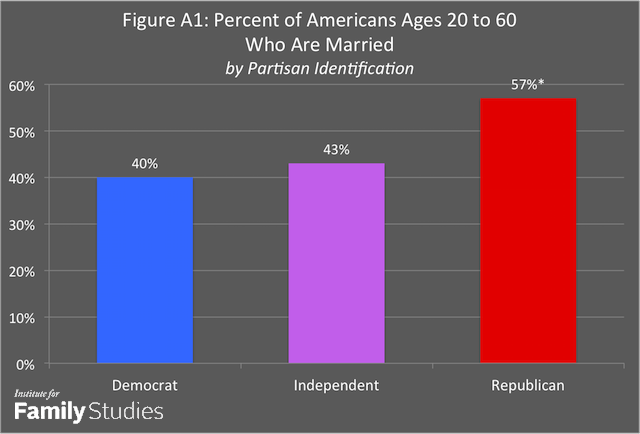

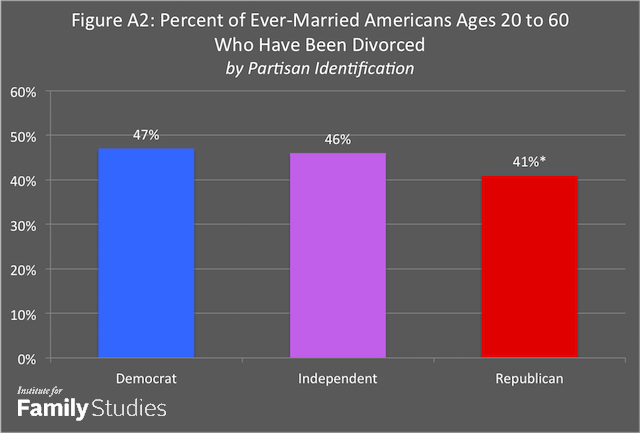

Our analysis of adults aged 20 to 60 in the 2010-2014 General Social Survey (GSS) casts doubt on Smith’s contention. Forty percent of Democrats are currently married, versus 57 percent of Republicans.1 Forty-seven percent of ever-married Democrats have been divorced, compared to 41 percent of ever-married Republicans. These data are cross-sectional, so we cannot be sure about the causal relationship between party identification, marriage, and divorce.2 But the data lend no empirical support to the view that blue families are more stable.

Instead, the GSS data and our earlier research suggest that an elective affinity—based on region, religion, culture, and economics—has emerged in the American electorate: married people are more likely to identify as Republican and unmarried people are more likely to identify as Democratic. Given that marriage generally stabilizes family life, and that there is an affinity between marriage and conservatism, it may well be that it is actually conservatives and conservative regions that are better at fostering “stable two-parent families in a post-industrialized world.” More research is needed to investigate the effect of ideology and region on family stability over the life course.

But stability is only one measure of the character of family life. We further took up Noah Smith’s challenge by exploring how partisanship is related to another important family-level outcome: marital quality. The benefits of a happy marriage include better physical and psychological outcomes for adults, and, for couples who have children, better emotional and marital outcomes for their sons and daughters. Our main question in this research brief is simple: are red or blue spouses happier?

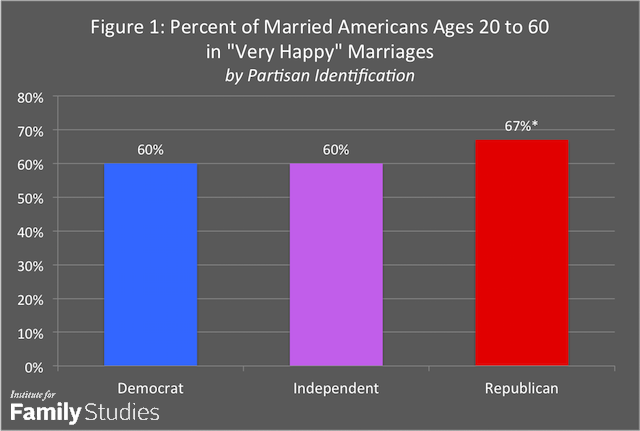

Source: 2010-2014 General Social Survey (GSS). *Difference is statistically significant at p<.05.

According to our analysis of the 2010-2014 GSS, red spouses are happier than blue spouses in their marriages. Married men and women between 20 and 60 years of age who are Republican are seven percentage points more likely than Democrats (and independents) to say they are “very happy” in their marriages. This is a statistically significant difference in marital quality.

Why are married Republicans happier than their Democratic counterparts? Perhaps the partisan divide can be accounted for by differences in the demographic and cultural composition of each party. After all, prior scholarship has found that marital quality varies by sex, race/ethnicity, education, and religiosity. In turn, each of these factors is linked to partisan identification in America. Women, minorities, and less religious Americans are more likely to identify as Democrats. By contrast, men, whites, and more religious Americans are more likely to identify as Republicans. (We also find a modest Republican advantage in college education in the 2010-2014 GSS.)

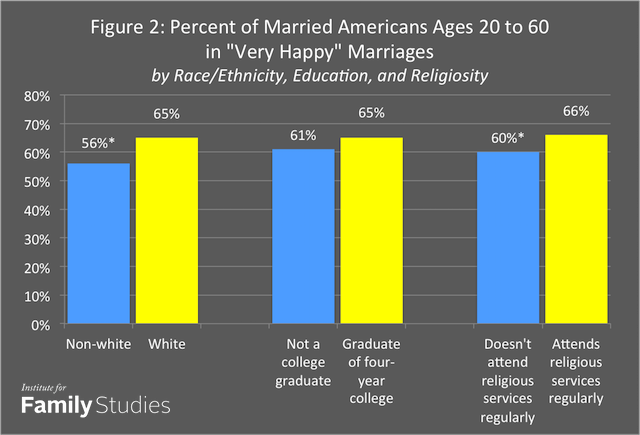

Source: 2010-2014 GSS. *Difference is statistically significant at p<.05.

The figure above shows that there are indeed differences in marital quality by race/ethnicity, education, and religious service attendance among GSS respondents. Whites, college-educated Americans, and churchgoing Americans are more likely to report that they are very happy in their marriages, although the education difference isn’t statistically significant. So how do these compositional differences help us to understand partisan differences in marital quality?

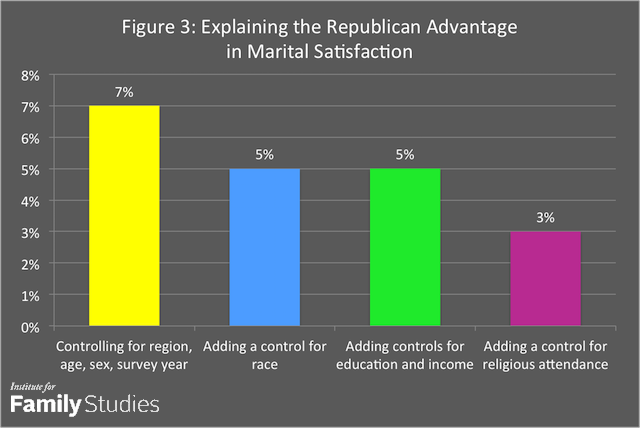

Source: 2010-2014 GSS.

As the figure above indicates, race and ethnicity clearly contribute to the red-blue divide. Once we factor in differences in marital quality by minority status, the Republican advantage shrinks. This suggests one reason Republicans have happier marriages is that, as a party with a larger share of white couples, they are less likely to face the discrimination, segregation, and poverty that minority couples often experience in America, all of which can compromise the quality of married life.

What about education and income? Given the centrality of social class in predicting better family outcomes for Americans, might the partisan difference in marital happiness be linked to these measures of socioeconomic status? No. The figure above suggests that socioeconomic differences do not help explain the Republican advantage.

Finally, we explore the extent to which religious service attendance drives the Republican advantage in marital quality. Churchgoing is associated with happier marriages, especially for couples who attend together. That’s because churchgoing couples enjoy more social, normative, and ritual support for their marriages and family lives. We find that religious differences account for a portion of the Republican advantage in marital quality, as the figure above indicates. In other words, once you control for religiosity, the Republican advantage in marital quality shrinks.

In sum, this Institute for Family Studies brief indicates that married Republicans are more likely than married Democrats to say they are in very happy marriages. Partisan differences in race/ethnicity and religious practice account for more than half of the GOP advantage, but we cannot explain the remainder of it. Perhaps Republicans are more optimistic, more charitable, or more inclined to look at their marriages through rose-colored glasses. But what we do know is this: Democrats do not enjoy an advantage over Republicans when it comes to the quality of their marriages. Further, the General Social Survey indicates that Republicans are also more likely to be married, and less likely to be divorced, than their Democratic fellow citizens. Our analysis of family-level data on marriage, divorce, and marital quality provides no support for the theory that blue families are superior to red families in America. Instead, the evidence suggests the contrary.

W. Bradford Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Nicholas H. Wolfinger is Professor of Family and Consumer Studies and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah. Their coauthored book, Soul Mates: Religion, Sex, Children, and Marriage among African Americans and Latinos, will be published by Oxford University Press at the beginning of 2016.

Appendix

Source: 2010-2014 GSS. *Difference is significant at p < .001.

Source: 2010-2014 GSS. *Difference is significant at p<.01.

1. Respondents who indicated that they were “independent-leaning Democratic” were coded as Democrat, while those who indicated they were “independent-leaning Republican” were coded as Republican. This coding is consistent with current scholarship in political science.

2. We are aware of no published longitudinal research tracking individuals’ partisan identification, marital quality, and family stability over time. Nevertheless, in exploring the association between geography, partisanship, and marriage patterns for today’s young adults at the county level, the Upshot found the following: “The more strongly a county voted Republican in the 2012 election, the more that growing up there generally encourages marriage.”