Highlights

- Paid family leave in Canada has normalized the importance of parent-child attachment in the first year of a child’s life. Post This

- However, Canada's paid leave program assumes and even directs parents to return to their previous employment status, especially with the recent addition of a so-called national day care plan. Post This

- Parental leave policies need to be situated within larger family policies that prioritize parental freedom and flexibility. Post This

The subject of heated political discussions in the United States right now has been a routine part of Canadian life for decades. Both maternity and parental leave are uncontroversial north of the border for those on the left and the right. That said, Canadian parental leave is not problem free and is subject to ongoing conversations about improvements. While we have our own thoughts on how Canadian family leave might improve, at the most basic level, it is a social good to both allow and encourage parents to spend time bonding with their new babies.

Here we briefly review paid parental leave in Canada and raise questions from our observation of these programs to help inform debate south of the 49th parallel.

The Nuts and Bolts of Canada’s Parental Benefit Programs

Canadians have access to unpaid, job protected leave regulated by our provinces and territories. While leave is administered through the federal employment insurance program, one province, Quebec, has its own program that provides a significant contrast to the rest of Canada.

Outside Quebec, benefit amounts are adjusted annually and both parents can take their portion of the sharable parental leave concurrently or consecutively. Parents must accumulate 600 hours of eligible employment in the previous 52 weeks to qualify. Self-employed workers are eligible but must opt into the program 12 months before claiming benefits and earn at least CAD $7,555 (about USD $5,600) net income.

Low-income families earning up to CAD $25,921 (about USD $19,220) can receive a Family Supplement that increases the parental benefit up to 80% of insurable earnings, instead of 55 percent. This is based on household income and the number and age of children in the home.

The Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) offers a maternity benefit, sharable parental benefit, and a non-sharable paternity benefit. This is intended to incentivize fathers taking time off with their children. To qualify, parents must earn a minimum of CAD $2000 (about USD $1483) in the qualifying period (usually 52 weeks).

Parental leave policies need to be situated within larger family policies that prioritize parental freedom and flexibility.

In short, both Canada and Quebec have a work requirement to pay into the system, though Quebec’s is substantially lower. Quebec also distinguishes itself from the rest of Canada with higher payout rates.

Ultimately, both programs offer what will seem like impossibly long paid and/or protected leave to Americans: up to 18 months at a lower payout rate in Canada and just over a year if the maximum amount of leave is claimed in Quebec.

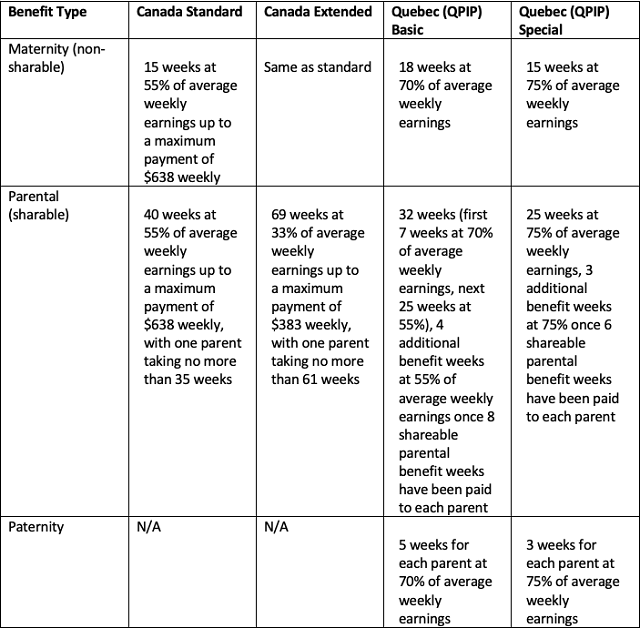

The chart below gives a quick look at the different leave features.

Are the Cultural Messages Communicated by Parental Leave Compatible?

A positive implication of paid family leave in Canada is that it has normalized the importance of parent-child attachment in the first year of a child’s life. By reducing the financial burden on families, and by creating a legal framework for time off without fear of job loss, the program makes it feasible for families to focus on this important life stage—and many do.

However, the leave policy also signals the expectation that parents will return to full-time employment following leave—something that many parents do as well. With this reality, even with Canada’s generous provisions, it may be that protected leave is not too long but not long enough. It is widely accepted that the first three years of a child’s life are critical. This being the case, European nations permitting three years of paid leave are more in tune with child development than Canada’s program that somewhat arbitrarily allocates a year or 18 months.

This problem is exacerbated with the recent federal initiative in Canada to nationalize and heavily subsidize institutional child care. Our federal government is explicitly promoting institutional child care as an economic policy to boost the GDP. These two big-budget federal programs (leave and child care) are tied to employment, and once parents step out of the paid work force, government “investment” drops off.

Should Parental Benefits be Part of Employment Insurance (EI)?

Locating paid leave within employment insurance, a federal program primarily intended to offer temporary income support for unemployed workers, helps cover the liability, but there are practical challenges arising from operating the benefit out of the EI system. A frequent problem is that some parents change work or reduce their hours following the arrival of a child, then struggle to make the qualifying hours before their next child is born. Quebec provides an easier-to-obtain threshold, but this doesn’t eliminate the challenges that stem from locating the program within EI.

Another issue with locating paid parental benefits within EI is that it also contributes to uneven uptake particularly among lower socioeconomic parents. In addition to greater difficulty for part-time workers to meet qualifying hours, some forms of low-wage work don’t qualify. For other low-wage workers, 55% of their income is insufficient to qualify. Although the Family Supplement boosts the payout to 80% of earned income, the earnings cut-off amount ( CAD $25,921, about USD $19,220) has not been adjusted since 1997, and should be increased.

At bottom, nothing would make Canada’s commitment to nurturing a return to work via leave policy clearer than having the benefit delivered via the employment insurance system.

Conclusion

The availability of paid parental leave in Canada signals the importance of parent-child attachment and child development in the earliest months. Given the importance of the first three years of a child's life, there would be justification to extend leave in Canada beyond the 18-month option. Yet there are trade-offs to consider, particularly in locating the program within employment insurance.

The question is whether a leave policy can be designed to provide the flexibility parents need to determine the best way to organize their care and waged work. A government’s legal parameters can and do dictate cultural norms, at least to some extent. Thus, parental leave policies need to be situated within larger family policies that prioritize parental freedom and flexibility. We are both grateful for the presence of Canada’s generous parental leave policy. However, it assumes and even directs parents to return to their previous employment status, especially with the recent addition of a so-called national day care plan. Good policy can avoid these pitfalls, and so Americans should not feel conflicted about creating the right parental leave policy to incentivize the importance of parents spending time with their babies at home in the early years.

Andrea Mrozek is a Senior Fellow with Cardus Family and Peter Jon Mitchell is the Program Director at Cardus Family in Canada.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.