Highlights

- Comparing across relationship status, adults who are married are by far the happiest, as measured by how they evaluate their current and future life. Post This

- The Gallup data from 2020 to 2023 show that marital status is a stronger predictor of well-being for American adults than education, race, age, and gender. Post This

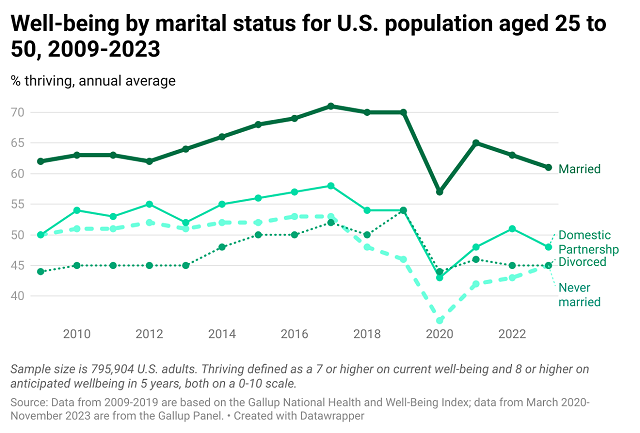

- In 2023, married adults ages 25-50 are 17 percentage points more likely to be thriving than adults who never married, up from 12 percentage points in 2009. Post This

- Communities are happier when more married people live there and when children are being raised in married households. Post This

At least since humans could read and write and likely earlier still, people have debated the merits of marriage. Anthropologists have shown that marriage is a cultural universal, found in every society from hunter-gatherers to ancient empires. Lectures from the Roman stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus contain much on the subject of marriage, including its benefits to individuals (saying no union is more necessary or agreeable), its proper aim (procreation as well as companionship and love), and its effects on society, saying: “Anyone who deprives people of marriage destroys family, city, and indeed, the whole human race.”

Measuring Well-Being

While we don’t have quantitative measures of the ancient world, Gallup has what may be the largest database ever created on subjective well-being. From 2008 to 2020, Gallup collected data from 2,578,342 U.S. adults, mostly via phone surveys, and from March 2020 through November 2023, Gallup collected an additional 56,653 responses through the web.

Two valid and reliable measures of subjective well-being—the Cantril ladder—were included on those surveys:

Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to ten at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?

The second item builds off the first, but asks: “On which step do you think you will stand about five years from now?” Respondents could pick options from 0-“worst possible” to 10-“best possible” for each item. Gallup social scientists code someone as thriving if they score a 7 or higher on current life evaluation and an 8 or higher on future life evaluation. Thus, to be thriving in well-being means to consider your life as near the best you can imagine in the present and likely to be near the best possible life in the coming future.

Yes, Married People Report Higher Well-Being

Comparing across relationship status, adults who are married are by far the happiest, as measured by how they evaluate their current and future life. In 2023, married adults ages 25 to 50 are 17 percentage points more likely to be thriving than adults who never married, up from 12 percentage points in 2009. The gap favoring those who are married is consistently large over the entire 2009 to 2023 period, though it ranges from a low of 12 percentage points to a high of 24 percentage points.

The large gap in well-being favoring married people is not explained by simple demographic differences. The gap from 2020 to 2023 is 20 percentage points after adjusting for race, ethnicity, age, educational attainment, and gender. In fact, within each gender and race/ethnicity, married people report significantly higher well-being compared to those who never married. Both married men and married women see a 20-percentage-point advantage compared to their same-sex peers who never married (see Supplemental Table 1 in the Appendix).

The same is true for adults who are American Indian, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Multiracial, or White. For instance, married Black Americans enjoy a 13-percentage-point advantage in well-being over their never-married peers.

This does not mean that marriage—as an institution or relationship—is necessarily the cause of a better life, though that certainly may be true. People who are persistently happier—or have attributes that tend to generate and sustain happiness, such as character traits like agreeableness, emotional stability, and conscientiousness—may be more likely to seek out marriage and may be more likely to receive marriage proposals. Marital status is not randomly assigned.

Still, the effect of marriage is high. Educational attainment predicts well-being, but a married adult who did not attend high school evaluates life higher, on average, than an unmarried adult with a graduate degree, after adjusting for gender, race, and age. The Gallup data from 2020 to 2023 show that marital status is a stronger predictor of well-being for American adults than education, race, age, and gender (see Supplementary Table 1 in the Appendix).

Download this chart here.

The marriage premium is not explained by political party preference, religious affiliation, nor, entirely, by household income. Adjusting for household income lowers the marital premium by about half—not surprisingly since the most obvious practical advantage of marriage is the pooling of resources, but married people remain significantly more likely to be thriving (9 percentage points) even after controlling for household income (see Supplementary Table 2 in the Appendix).

Moreover, these data also show that Republicans are significantly more likely to be thriving in their well-being compared to Democrats and Independents/third-party supporters, by 9 to 12 percentage points. Likewise, people with a religious preference are more likely to be thriving than atheists, agnostics, or those with no preference (by 6 percentage points). Yet, controlling for these things does not lower the effect of marriage, even though married people are more likely to be both Republicans and religious.

People Report Higher Well-Being in Places With Higher Marriage Rates

The individual link between well-being and marriage plays out on the larger scale of towns, cities, or groups of cities that share commuting links. People living in metropolitan areas with higher rates of marriage enjoy higher subjective wellbeing.

The data are from 2016 to 2020. To measure well-being at the metropolitan scale, I updated a database published for the Brookings Institution with my co-author Andre Perry. This combines Gallup data from 2010 to 2023, so that even small areas have enough responses for reporting (100 is cutoff used here). In total, we have data on 919 metropolitan and micropolitan areas. These areas are based on the county or counties (or county equivalent entities) with at least one urban area consisting of 10,000 residents and the smaller adjacent counties that have strong commuting ties. Micropolitan areas are centered around an urban area that has between 10,000 and 50,000 residents, where a metropolitan area is based on an urban area with at least 50,000 residents.

Consistent with the individual analysis, well-being is measured as the percentage of adults who are thriving. I weighted the responses by the population size (ages 15 and over) to make the results more representative of the places where people live, thereby answering the question: “Are people living better lives where marriage rates are high?”

Marriage rates can be measured in several ways. First, I looked at the share of households that are married across metropolitan areas, where the Census defines a household as people sharing a home or housing unit. This has a modest but significant correlation with the percentage of adults thriving in their wellbeing (0.19). The problem with this is that some cities attract many young unmarried people for work or school or retired widowers, but the area may still have high marriage rates at middle-age when child-rearing is more likely.

For these reasons, I also looked at the relationship between well-being and the share of people aged 35 to 54 who are married. This has a stronger association with well-being (r = 0.35). Finally, I looked at the share of children living in married-couple household. This was even more closely related to well-being (r = 0.41).

In America at least, it looks like well-being ebbs and flows with marriage.

Of course, as with the individual analysis, one would want to consider how communities differ aside from marriage. So, I ran regression models that adjust for the share of people in different age groups (15 to 19, 20 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, and 65 and over), as well as the share in each of the major racial and ethnic groups, the share of population aged 25 and over with a Bachelor’s degree or higher, and the population size of the area. I also considered the share of votes that went to Donald Trump in the 2020 election and the rate of religious adherence.

For each measure of marriage, I find a statistically significant relationship between the marriage rate and well-being. The strongest measure is the share of households who are married. A 5-percentage-point increase in this marriage rate (1 standard deviation) predicts a 0.9 percentage point increase in the share who are thriving (see Supplemental Table 3 in the Appendix), which is about 0.19 standard deviations in well-being. The marriage rate has a similar effect size as the age composition and is somewhat less predictive of metro area well-being than education. By comparison, an increase of one standard deviation in the Bachelor’s or higher attainment rate (0.09) predicts a 0.49 standard deviation increase in well-being.

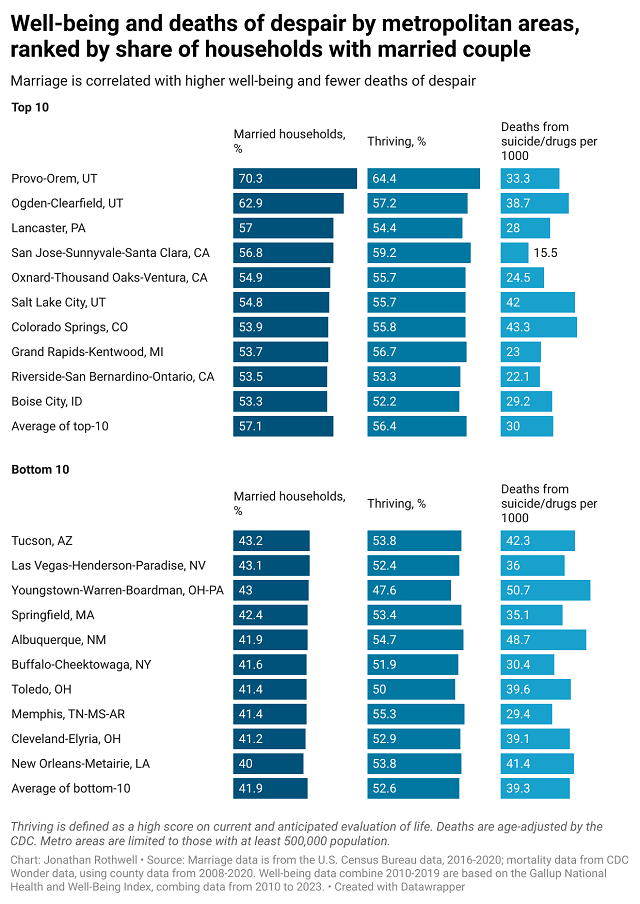

The community-level well-being link to marriage is not limited to subjective well-being. Using an objective measure of well-being—or lack thereof—yields the same results. In my analysis with Andre Perry of Brookings, we found that subjective thriving was highly and negative correlated with deaths of despair at the metropolitan scale.

Here, I run models predicting the age-adjusted rate of deaths of despair, defined as deaths from suicide, drug or alcohol poisoning, or overdose. Again, marriage rates are strongly predictive—in this case negatively related to deaths of despair. The effect is even larger than the Bachelor’s degree attainment rate.1 In fact, the marriage rate measures are each more important than the college attainment rate, age composition, or racial composition in predicting deaths of despair.2 (see Supplemental Table 3 in the Appendix).

In the figure below, I rank metropolitan areas by the share of households that are married for all areas with at least 500,000 residents.

Download this chart here.

Provo, Utah, happens to have both the highest rate of subjective well-being (64.4% are thriving) and the highest household marriage rate (70%). Ogden, Utah, is second on the marriage rate (62.9%) and also enjoys a high rate of well-being, as does the San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA, metropolitan area and Grand Rapids, Michigan. Among the top 10 areas for marriage per household, the average share thriving in well-being is 56.4%, compared to a group average of 52.6% for the 10 areas with the lowest marriage rates per household. On this list, Cleveland and Las Vegas have well-being rates below 53%. Youngstown and Toledo have thriving rates at or under 50 percent.

One could also rank metropolitan areas by the share thriving and observe marriage rates. Doing so, I find that, after Provo, Urban Honolulu has the second highest well-being (62.2% are thriving), among metropolitan areas with at least 500,000 people, followed by Washington DC (61.9%), Austin (60.7%), San Jose (59.2) and San Francisco (58.8%). As they attract many young workers, these places do not have especially high percentages of households who are married, but they score very high on the percentage of children raised in married households (72% to 78%).

Conclusion

Marriage is a legal and cultural institution that, at least in part, symbolizes, establishes, celebrates, and cements a profoundly intimate partnership between adults. Identifying the precise causal effect of marriage on mental health or well-being through statistical analysis is likely beyond the capacity of social science.

Yet, it is relatively easy to observe that married people enjoy higher well-being, when asked to reflect upon their life. They evaluate their current and future lives as being closer to the best possible life. They are much less likely to be struggling or suffering in their well-being, as defined by Gallup. Likewise, communities are happier when more married people live there and when children are being raised in married households. At the individual level, marriage has a larger predicted effect on well-being than other common demographic variables, except household income, which marriage usually raises. At the MSA scale, marriage is not as predictive of subjective well-being as educational attainment, but accounts for much of the variation and is more important than income, political orientation, race, and religious adherence. Marriage rates are more predictive of metro area deaths of despair than these other factors. In sum, in America at least, it looks like well-being ebbs and flows with marriage.

Download the full IFS/Gallup research brief here. Download the Appendix tables here.

Jonathan Rothwell is the principal economist at Gallup and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

1. An increase of one standard deviation in the share of households married, predicts a -0.24 standard deviation decrease in deaths of despair. The effect size is -0.51 using the share of children living in married households, and for the Bachelor’s attainment rate, the effect size is -0.16.

2. The log of median household income was also included in an additional model predicting deaths of despair, but it was not significant using two of the three measures of the marriage rate, each of which remained significant. The inclusion of the log of income resulted in a weakly significant and negative relationship when the married household share was used, but it was weaker than the marriage share, and the latter remained significant.