Highlights

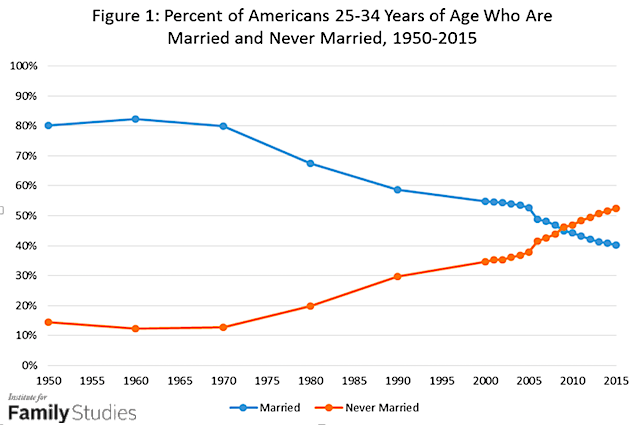

For almost a half a century now, social scientists have observed what they call a “retreat from marriage,” although the reasons for the retreat continue to be debated. The figure below shows this retreat among American men and women ages 25 to 34. The change started about 1970. In that year, 80% of 25- to 34-year-old Americans were married. By 2015, only 40% of this age group were married. People can be “unmarried” because they are widowed or divorced (not shown in the graph), or because they have never married. Figure 1 shows a large increase in the proportion who have never married, from 5% of this age group in 1970 to 50% by 2015.

Source: U.S. Census, 1950-2000; American Community Survey, 2001-2015.

The “retreat from marriage” comes from some people marrying later than was common in previous decades, while others never marry. There is little evidence of an increase in the proportion of Americans who decide early in life that they never want to marry. But if marriage is delayed long enough, it may never happen. A recent report by sociologist Steven Martin and colleagues at the Urban Institute estimates that somewhere between 23% and 31% of women, and 27% to 35% of men born in 1990 will not marry by age 40.

In his just-published book, Cheap Sex, sociologist Mark Regnerus argues that an important factor in the declining share of Americans who are married is that sex is easily available and no longer depends on marriage. In this blog post, I’ll consider Regnerus’ arguments for the claim that “cheap sex” helps explain the decline in marriage, noting which of his points I find more and less plausible. I will also provide evidence for another factor behind the retreat from marriage—the fact that men without a college degree have increasing difficulty finding and holding jobs, especially decent-paying ones.

“Cheap Sex” and the Retreat from Marriage

Regnerus argues that three key technological changes have made sexual gratification more readily available: 1) the birth control pill, 2) free online pornographic videos, and 3) internet dating apps, which make it easier to find partners for either quick sex or enduring relationships.

To my mind, the biggest game-changer was the birth control pill, which became available to single women in the late 1960s, making it possible to have sex with a low probability of pregnancy. Previously available methods (condoms, diaphragms, withdrawal, and rhythm) have much higher failure rates. Economists Claudia Goldin and Martha Bailey have marshaled statistical evidence (see here and here) that the availability of the pill increased the proportion of women who finished college and began a career. It did so, in part, by allowing women to delay marriage for years without having to delay sex.

The pill is clearly not the whole story of why age at first marriage increased, however, since recent research of mine with Larry Wu and Steven Martin showed that approximately 40 to 50% of women born in the late 1930s and early 1940s had premarital sex, despite coming of age before the birth control pill was widely available. Consistent with the role of the pill facilitating premarital sex is the finding that there was a steep increase in premarital sex between those born in the early 1940s and those born in the next two decades, reaching 80% of those born in the 1960s. Thus, I agree with Regnerus’ claim that the pill’s facilitation of more worry-free sex contributed to delaying marriage. One of the reasons that many of our grandparents married by age 20 was undoubtedly to be able to have sex; with the pill, later marriage became more compelling.

While Regnerus grants that the pill enhanced women’s education and careers, the theme of his book is the negative consequences of “cheap sex.” He focuses in on how sex became cheaper for men in the sense that they now need to offer little in the way of commitment or economic provision to get it. The crux of Regnerus’ argument about marriage is that men have less incentive to marry or stay married today because they can get sex without doing so. It is not only that men can get sex outside of marriage; casual sex via “hookups” or the use of apps like Tinder is available with no exclusive relationship at all. He argues that this is bad for women, in particular, citing as evidence that some women wish the men they are dating would “put a ring on it” but have a hard time moving things in that direction.

Of course, if men and women were equally desirous of sex, we wouldn’t expect men to have to offer women anything —such as marriage or economic support—in order to obtain it. Critical to the logic of his argument is his belief that men are more desirous of sex than women. One piece of evidence for this is higher rates of masturbation among men than women across cultures.

I’ve sketched above what I see to be the stronger parts of Regnerus’ argument. Other parts I find dubious. While there is evidence that men are more interested in casual sex than women, on average, I question whether we can be sure that this difference is “hard-wired.” Women’s lesser interest may result from being more harshly judged for casual sex than men. (Regnerus believes that this cultural double standard is itself hard-wired, for reasons I don’t understand; see p. 64-65 of his book.) He worries that the ready availability of free online pornography further erodes women’s power to get men to commit. As he colorfully puts it, “a laptop never says no.” My fear about porn is that it normalizes sexual scripts sorely lacking in mutuality; I find it less plausible that men will find it a good enough substitute for real women to have much effect on marriage rates. Regnerus worries that online dating apps discourage commitment because they remind us that there are always thousands of better options out there. Perhaps, but online dating also allows those seeking long-term relationships to find compatible partners more efficiently.

Regnerus is right that the ability to have sex with few strings attached is one reason couples in all social classes increasingly delay marriage. But why is the retreat from marriage much steeper for those with low or moderate education?

Men’s Employment and Earnings and the Retreat from Marriage

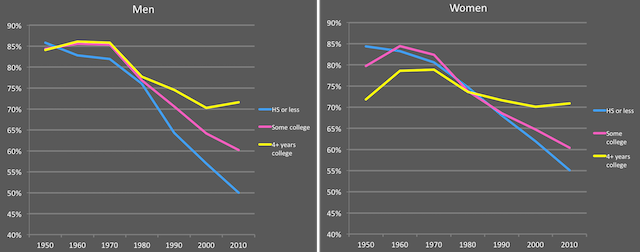

The retreat from marriage is more pronounced among those with less education. The graph below, pertaining to those ages 30 to 44, shows the percent of American men and women of each education level who were married since 1950. After about 1980, the decline is much steeper for those with less education. This reflects a combination of two facts: Since 1980, divorce has decreased more among college graduates than those without a college degree, and the proportion who never marry has increased more among less educated. As for the latter factor, the Urban Institute report mentioned above estimated that of men born in 1990, 32-41% of those without a college degree will not marry by age 40, compared to only 19-22% of college graduates, with a similar educational gap found for women.

Figure 2: Percent of Men & Women, Ages 30-44, Married in 1950-2010, By EdUcation

Source: Computations by Shelly Lundberg using 1950-2000 U.S. Census and 2010 ACS data.

This growing class gap in marriage implies that we don’t have a complete explanation of the retreat from marriage until we identify some factor that has changed much more for those without college degrees. This is a huge group—approximately two-thirds of all American adults.

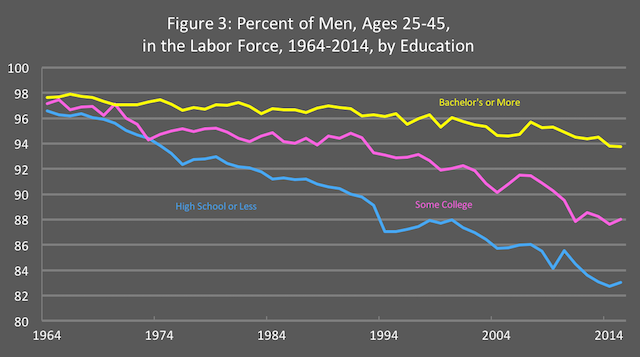

Many sociologists believe that part of why marriage is diverging by class is the increasing inequality by education in men’s employment and earnings, documented in many studies. A 2016 report from the White House details trends for “prime age” men—those ages 25 to 54 when few are still in school or already retired. Fifty years ago, 96-98% of men of all education levels were in the labor force, meaning they were either employed or looking for work. Figure 3 below, taken from the report, shows that beginning in the mid-1960s, the percent in the labor force declined for men of all education levels. But the decline was small for college graduates—dropping from 98 to 94% between 1964 and 2014. The decline was much steeper for less advantaged men—only 83% of those with a high school degree or less were in the labor force by 2014.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (Annual Social & Economic Supplement); CEA calculations.

The same White House report showed that among men who were working, starting in the mid-1970s, men’s wages diverged strongly by education. Whereas in 1975 the hourly earnings of men with a high school degree were 80% of the amount earned by workers with a college degree, by 2014 this ratio was only 60%.

Why would this affect marriage? While tradition has given way enough that wives having jobs is now widely accepted, it is less acceptable for husbands to be without a job. Neither the man nor woman of a couple may see getting married as appropriate if the man doesn’t have a stable job. For men who are already married, not having a job increases the risk of divorce, probably because of this same norm that husbands should have jobs.

Why the Retreat from Marriage?

Those who get college degrees typically have sex before marriage, using contraception to avoid pregnancy. They marry late, but ultimately marry at higher rates and have lower divorce rates. Most men who are college graduates are employed, and their earnings compared to less educated men have increased. They too have seen a retreat from marriage, but only in the sense that their marriages occur later. For them, this has little to do with economic woes. Both husbands and wives are often employed as professionals, in part, because the availability of birth control facilitated more education and delayed marriage.

The picture looks very different for those who are less advantaged. A growing percent of men without a college degree are not in the labor force. Wages among men without college degrees have fallen relative to those of college graduates. The retreat from marriage among these less advantaged men is not just matter of them marrying later to get an education and build careers; they often manage to do neither. Some do not marry at all, although most will have children, and those who do marry divorce at relatively high rates. Their economic woes are probably a big part of their retreat from marriage. While attitudes are now very accepting of two-earner couples, they are less accepting of a “reverse-role” situation where the husband is not a breadwinner at all.

Regnerus is right that the ability to have sex with few strings attached is one reason couples in all social classes increasingly delay marriage. But why is the retreat from marriage much steeper for those with low or moderate education? Cheap sex can hardly explain this class divergence because access to sex in early adulthood is just as great for those who become college graduates. For many farther down the class hierarchy, men’s economic woes are also key barriers to getting or staying married.

Paula England is a Silver Professor of Sociology at New York University. The author of Comparable Worth: Theories and Evidence, Professor England is also past president of the American Sociological Association.

Editor’s Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.