Highlights

In 2007, Patriarch Ilia II of the Georgian Orthodox Church made a decision: facing a country with a declining population, low birth rates, and high abortion rates, the church leader announced that he would personally baptize and become godfather to any third-or-high Orthodox child born to a married couple in Georgia and formally registered with the government. Georgia is almost 90% Georgian Orthodox, Patriarch Ilia II is widely trusted and respected, and Georgians are the most likely of any Orthodox-majority country to say their religion is about personal faith. In other words, Georgia is an ideal test-case to see if national leaders can use social or cultural capital to effect targeted social changes. Since the first mass-baptisms in late 2007, Ilia has baptized over 30,000 babies, about 5.8% of the total births in Georgia over that time, or about 34.5% of the third-or-higher births, so his baptisms are of a demographically-significant scale.

Recently, I wrote about how using financial incentives to boost fertility may cost a lot more than policymakers expect. This could reasonably lead a reader to think that any boost to fertility will be very expensive. But that’s not necessarily the case. It is widely demonstrated, for example, that a woman’s fertility desires are closely associated with religious belief—with more religious people usually desiring more children—and yet religious belief has no direct fiscal cost for the government.

It stands to reason, then, that cultural or social changes might impact fertility as well. However, cultural and social changes are very hard to discuss because they are rarely tracked with sufficiently detailed data to allow rigorous analysis, and it’s often hard to show causality: is fertility impacting culture, or culture impacting fertility?

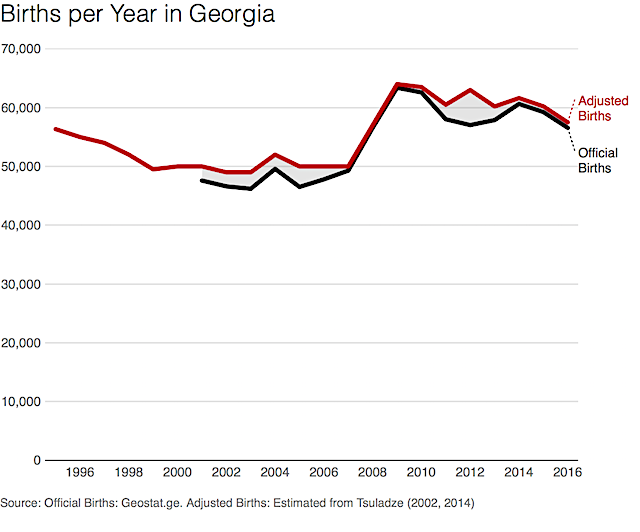

Fortunately, Georgia, a small former Soviet republic of just 3.4 million people wedged between Turkey and Russia, undertook a radical experiment. Can a popular social figure alter birth rates by bestowing special honors on high-birth-order children? Georgia’s official statistical agency tracks the data we need to answer this question. We can start simply by looking at the number of births in Georgia:

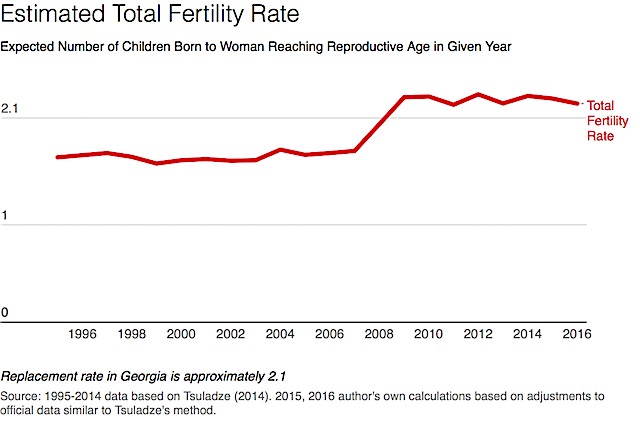

As you can see from the figure above, there’s a sharp spike in births in 2008. News reports and politicians at the time attributed this rise to the patriarch’s pro-fertility, anti-abortion campaign. However, the official Georgian statistics slightly undercount births; I will instead use the adjusted statistics shown above, in keeping with the methods used by leading experts on Georgian demographics.

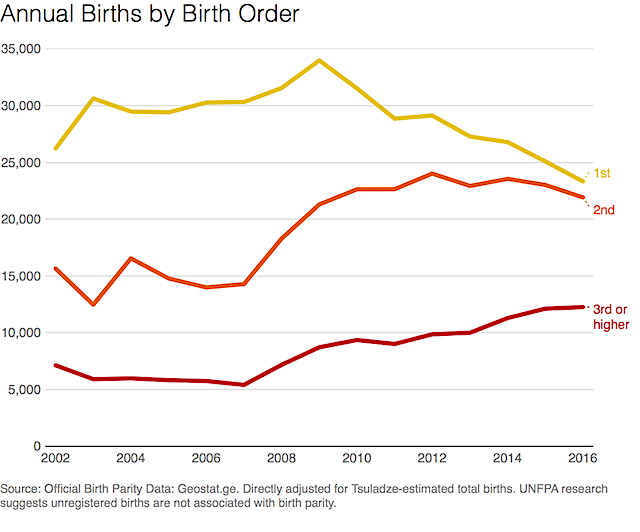

But was Patriarch Ilia’s campaign really the cause of this rise? The simplest way to test this theory is to see if that increase was mostly among third births or higher, the babies who would be able to be baptized by the patriarch.

In this figure, we can see that from 2007 to 2008, births rose for every birth parity. From 2008 to 2009, they rose again for every birth parity. But from there, first births declined, second births stayed flat, while third births continued to rise. This is suggestive evidence that Patriarch Ilia’s campaign may have worked: third-order births nearly doubled between 2007 and 2010, and then continued to rise over time. Crucially, it is possible that his campaign could boost even first or second births if parents hope to have more babies later to take advantage of the offer of special baptism for future children. They may push the timing of their planned births forward, as Patriarch Ilia is not a young man and his successor might not commit to the same schedule of mass baptisms.

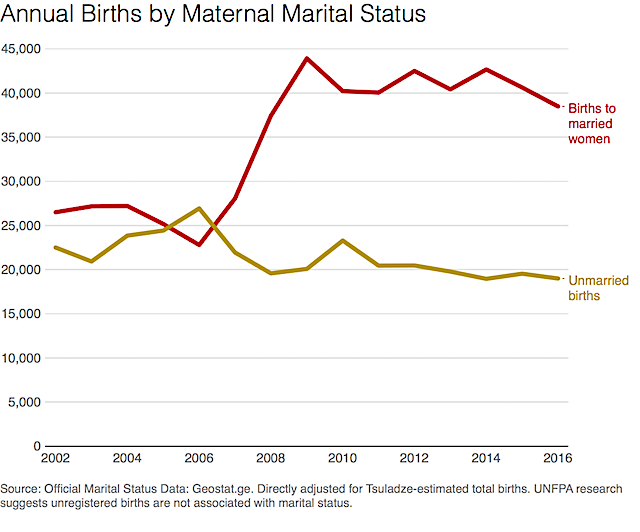

But is the spike in first and second births really about couples accelerating fertility to get the patriarchal baptism? Well, it’s hard to say for sure, but we can also subdivide fertility by marital status. The offer of baptism was only officially extended to married couples, so one might expect married fertility to spike upwards, while unmarried fertility should be unaffected.

As the figure above indicates, the entire observed fertility increase occurred in married fertility, while unmarried childbirth actually fell. Now, married childbirth was rising slightly even before 2008, the first year when Ilia’s policy can really be expected to have had a significant effect, which suggests there may have been an underlying trend upwards. But the divergence is so large and persistent that, combined with the birth-order data shown above, it seems extremely likely that much of this jump was due to Patriarch Ilia’s offer of baptism.

Social commentators sometimes wonder how much societal problems may depend upon questions of what we call social capital, which basically means the extent to which people trust each other and can intentionally influence each other. It’s often hard to put our finger on how these less quantitative factors matter. But the case of Georgia is pretty clear and shows that the presence of social capital—meaning a non-state actor who can influence the behavior of others without coercion—can be an enormous asset to a society, enabling them to make demographically-significant changes with a comparatively low price tag.

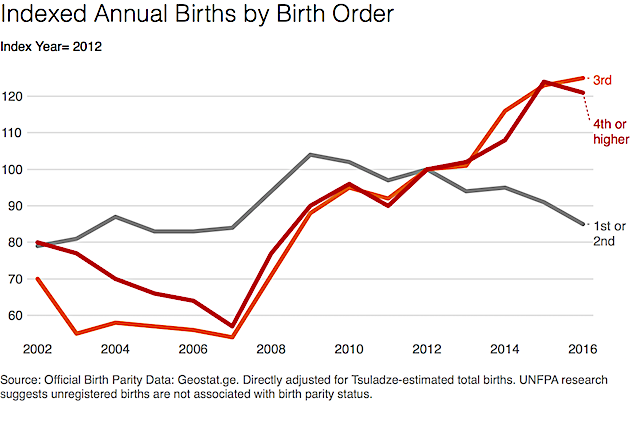

But there’s a twist ending to this story. In 2013, Georgia greatly expanded its financial incentives for childbearing. Paid parental leave was extended from 126 to 183 days and unpaid leave from 477 to 730 days. Likewise, the government increased the “baby bonus,” a one-time payout for having a child, from about $250 to about $400 (Georgia’s GDP per capita is only about $9,000), and they increased the bonus for a fourth child to nearly $800. Then, in 2014, they launched another expansion, offering parents of three or more kids in low-population regions an $850 annual payment.

So if moderately-sized financial incentives boost fertility, we should expect that, in 2013 or 2014, childbearing generally should rise, and fourth or higher childbearing should rise even more. And in 2014 or 2015, third or higher childbearing should rise.

Fertility for first and second children continued to fall despite the new incentives, perhaps suggesting many families had shifted their births earlier to take advantage of the baptism offer, and the share of women who could have a first birth was smaller than in previous years. But higher-parity births did continue their rise (see figure above).

However, the effect is inconsistent: despite having a bigger incentive offered a year earlier, fourth childbearing rose less than third. Financial incentives may have boosted fertility in these groups, but the observed trend doesn’t quite match what we’d expect if those incentives were the sole cause. Plus, the effect is substantially smaller than the effect observed from Ilia’s baptism offer, and, of course, the price tag far, far higher, with these programs costing Georgia an appreciable share of its budget.

Nonetheless, it seems plausible that the continued rise of higher-order birth after 2013, while lower-order births fell, could reflect expanded financial incentives. Giving money for kids does have some effect, just not as much as encouragement from beloved religious leaders.

These effects turn out to have a large impact on Georgia’s national-level fertility trends.

Before Patriarch Ilia’s policy, Georgia had below-replacement-rate fertility: they weren’t having enough kids to keep the population stable. After the mass baptisms began, the fertility rate rocketed to above-replacement levels and has stayed there for nearly a decade, suggesting that there is likely to be a discernible impact on completed fertility as well.

Fertility changes of this magnitude are not extremely common; many governments would kill for the ability to engineer this kind of policy. But Georgia’s case is unique: comparatively homogenous societies where one highly-respected religious leader has the social capital to induce these kinds of changes are extremely rare. The United States has never had that kind of social homogeneity, nor will it ever.

But there are subgroups in the United States where the exertions of still-respected institutions to promote childbearing and ease family life may matter. The choices made by universities determining whether childbearing is compatible with being a student or professor almost certainly impacts fertility. The views, attitudes, and enthusiasm for childbearing displayed by ministers likely have an impact on their parishioners’ marginal odds of having kids. The ability of social organizations to give honors and instill in their members a sense of familial pride almost certainly influences fertility. When we consider the puzzle of American fertility, these factors, not just economics, are a vital component: do family members discourage having the fourth child a family may want? Do churches celebrate children, or relegate families to cry-room isolation-chambers? Do universities subtly avoid advancing the careers of women with or expecting children, depriving students of role models who achieve their professional and familial ambitions? These questions are likely to drive fertility trends as much, if not more than, a few more bucks of government support. And although they may be cheaper to change, that does not mean the change is any easier.

Lyman Stone is an economist who blogs at In a State of Migration, and a proud Kentuckian. Lyman also works as an agricultural economist at USDA. His views are not endorsed by, supported by, or in any way reflective of the US government.

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.