Highlights

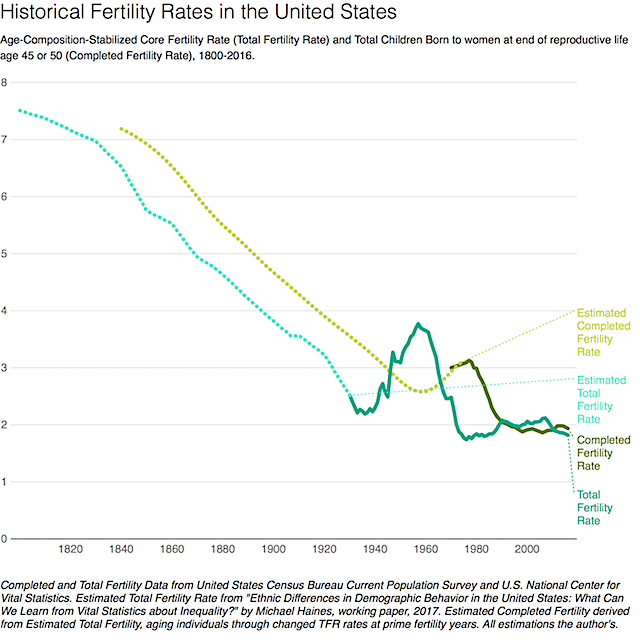

In light of new numbers just released by the CDC indicating that fertility fell again last year, American fertility rates remain at or near record-low levels even as a growing chorus of politicos on the left and the right call for increased government aid to families. The United States has seen below-replacement-rate fertility for nearly a decade now, meaning that the average woman who reaches reproductive age is expected to have fewer children than is necessary to maintain a stable population in the United States without including immigration. As a result, immigration now represents the vast majority of U.S. population growth.

And while there has been some hand-wringing, calls in the United States for policy aimed at boosting fertility remain more implied than explicit. Abroad, however, such “pro-natalist” policy is a common feature in many countries. The question, however, is if any of it works. If we give money or leave time to families, will it actually boost fertility?

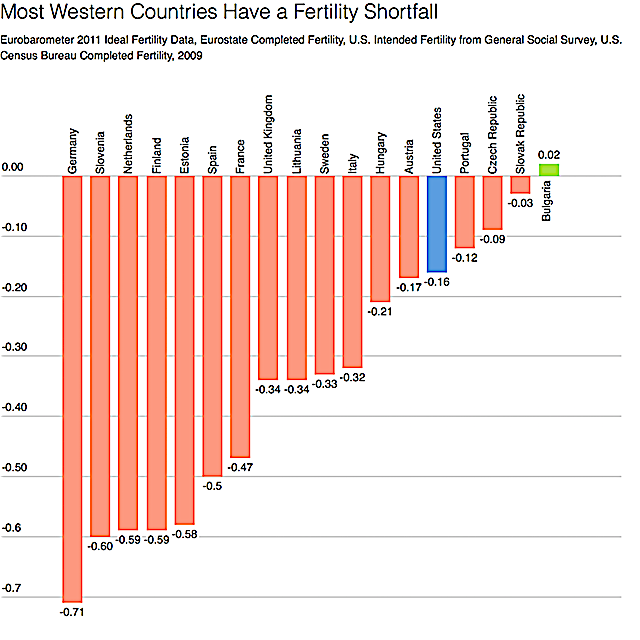

But even people who don’t think falling birth rates are bad in and of themselves may have reason to think boosted fertility is a good indicator. The logic behind this rests on what demographers call “desired” or “wanted” or sometimes “intended” fertility. That is, we can simply ask women how many kids they think would be ideal. Women are surveyed at many different ages, but one simple thing to do is to look at what women who are done having kids and compare that to how many kids they had. Using data from the OECD, we can do this, directly comparing completed fertility to the fertility those women think would have been ideal, had their life and family choices played out the way they wished. For the United States, I use “intended fertility” of women over 35, which probably understates this gap versus the European countries included.

As the above figure indicates, throughout the developed world, women are unable to obtain the fertility they desire. This is a crucial point, as all too often the politics of childbearing are phrased to suggest that the only policy goal a woman might have would be to reduce childbearing, when in fact most women probably only want to reduce accidental childbearing, and many women may have an interest in enabling higher fertility. Unsurprisingly, this fertility gap varies with educational levels, with more educated women more likely to experience a fertility shortfall, and less educated women more likely to experience more-than-desired fertility. In the United Kingdom, all educational levels experience a fertility deficit, perhaps owing to wider access to contraceptives among lower-income women in the UK than the US.

Why don’t women achieve their childbearing desires? There are many reasons, including the lack of a suitable partner and diminished biological fertility thanks to delayed first birth (which is itself largely a function of a higher educational system that is often incompatible with motherhood). However, any current or prospective parent will tell you one important reason: money! Having kids can be expensive. And unfortunately, the gap between realized and desired fertility is growing throughout the developed world. Thus, it stands to reason that if a policy change actually eases the financial situation for families, then fertility would almost certainly rise as families are more able to achieve their fertility goals. Closing this “fertility gap” by boosting fertility to its desired level is a vital test of whether a policy actually achieves pro-family goals in the real world. If the problem families face is money, then more money should mean more babies for at least some families, pushing observed fertility upwards.

Unfortunately, most policymakers don’t have a serious enough proposal to tackle this question. To see why, we can take a spin through the academic literature on pro-natal policy. We know China successfully reduced its fertility through policy tools, and at least one study suggests that legalized no-fault divorce also reduces fertility, and another study suggests that removing an educational subsidy reduced Taiwanese fertility, so there’s a good reason to think that policy can impact fertility.

But can we push fertility up? Some research says yes: 0.3% of GDP dedicated to an unconditional cash transfer to French families may have boosted short-run total fertility by 0.3 children per women. That’s a big effect! Another study of France, this one much longer-run, showed that its very family-friendly tax bracket structure boosts fertility as well. Research on a monthly child allowance in Israel suggests that each dollar per child per month boosted fertility about 0.01%. A one-time cash transfer ranging from $500 to $3,000 in Quebec may have caused a 10.7% to 25% increase in births for families in Quebec. A study of British welfare systems showed that a 50% higher per-child welfare outlay yielded 15% higher births. A “baby bonus” in Australia boosted fertility, but at the cost of over $100,000 per child. A special subsidy to have a second or third child in Russia boosted second childbearing by 2.2%. Meanwhile, various increases in the generosity of “maternity pay” in Romania and Germany increased childbearing as well. Finally, a study of pro-natalist policy throughout Europe suggested that while family allowance spending had little impact, family leave could boost first childbearing, and subsidized childcare could boost later childbirth.

But there’s a problem. Most of these studies looked at short-run fertility. That is, they show that after policy implementation, childbearing rises. But this could just be a timing shift. Maybe people have kids earlier but don’t increase total childbearing, so the true effect on fertility could be zero. Several studies addressed this in the above list, but the one to do so most persuasively was the study of German maternity pay. That paper showed that fertility rose even for women near the end of childbearing years, which seems likely to mean their completed fertility was pushed higher. However, the effect size for these older women was only about one-fourth as large as for younger women, so perhaps as much as 75% of the total fertility increase could be fleeting.

Another study of programs throughout the OECD, reviewing other papers, suggests most observed effects can be written off to shifted birth-timing: fertility policies may have no effect. An additional study of that British welfare change mentioned above suggests that all that really happened was births were shifted forward, so at least that one study result was probably invalid. A study of a Canadian family allowance shows an increase in short-run fertility, but shows no change in completed fertility. A more recent study of the Quebec program I mentioned earlier shows that the one-time cash bonuses had no impact at all on completed fertility which suggests, again, that fertility policy may have no durable impact at all. And perhaps most devastating of all, a study of the U.S. EITC program suggested that greater generosity to families may have slightly reduced fertility. So while some research suggests financial incentives boost fertility, other research suggests effects may be small, transitory, or perhaps may not exist at all.

The academic literature, then, is decidedly mixed. While policymakers can readily engineer a short-term baby-boom easily enough, their ability to boost long-run fertility and actually help families achieve their desired fertility level is far more constrained.

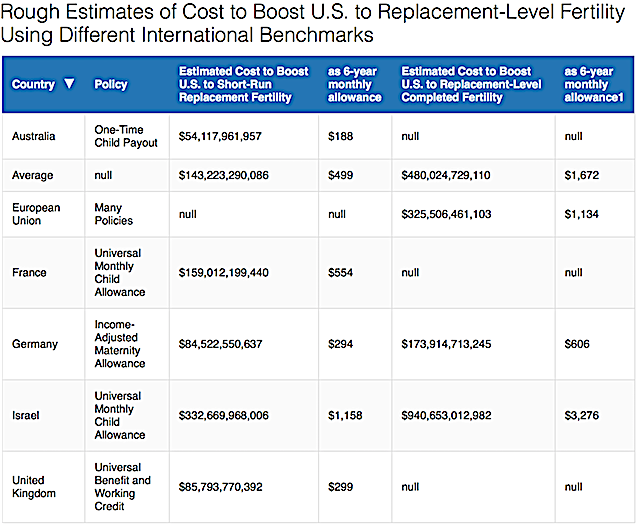

But let’s say the optimists are right and pro-natal policy works. If we plug in the implied elasticities from a few of these papers to the U.S. case, how much would it cost to boost our fertility just up to replacement rate? All such estimates will be fraught with error and should be taken with a heap of salt, but they can at least give us a general idea of what kind of program scale we’re talking about.

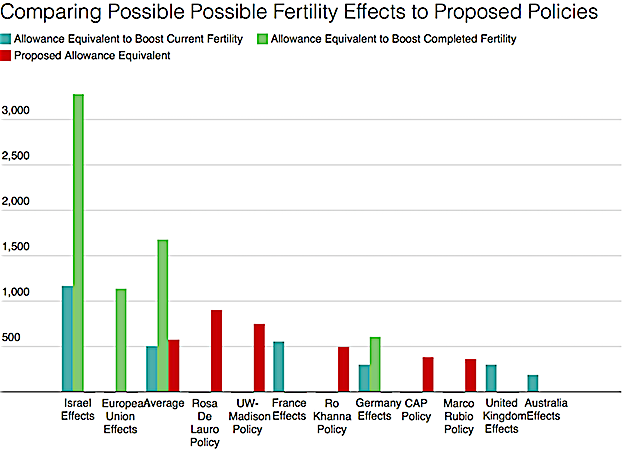

Across countries and policies used, there is an enormous difference in estimates of how much money it takes to boost fertility. For somewhere between $50 and $340 billion, U.S. total fertility rates could be temporarily boosted to replacement-levels. To boost completed fertility, you’d need to shell out between $170 and $950 billion; quite a bit more. And of course, surveys of women’s intended fertility in the United States show that, in every year, every age group of women actually wants to experience above replacement fertility, with intentions ranging as high as 2.5 births per woman. So even those high figures won’t actually give American families the fertility they really want, just the fertility necessary to stave off long-run population decline.

If we conceptualize these outlays as a “monthly child allowance” paid out for the first 6 years of a child’s life, then the minimum possible allowance would be nearly $200 per month or $2,400 per year, while one estimate suggests it would take as much as a $3,300 per month subsidy, or $40,000 per year, to boost completed fertility. That figure is an outlier, but it’s plausible to suggest that it might take substantially more than $1,000 per month per child to boost long-run fertility to replacement levels.

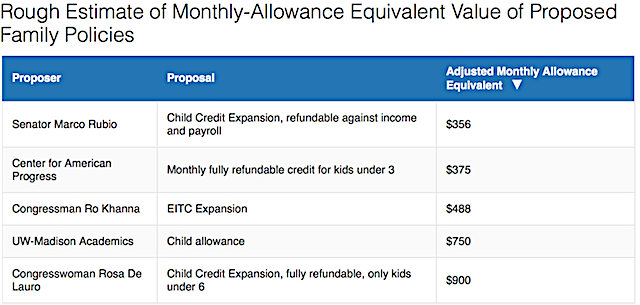

So, what proposals are on offer from pundits and politicians? A sampling of a few of the biggest proposals I’ve encountered advertising themselves as pro-family should give a sense of the upper limit of what U.S. policymakers are considering. None of these policies advertise themselves as attempting to boost fertility, but they are all structured in such a way as to reward childbearing, and thus plausibly increase fertility. Congressman Ro Khanna (D-CA) proposes a huge increase of the EITC to support working families. Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) would like to expand the child tax credit and make it refundable against payroll taxes. Congresswoman Rosa De Lauro would also like to expand the child tax credit, adding a second credit paid out monthly to families for kids under age 6. The Center for American Progress proposes a monthly refundable credit, but only for kids under age 3. Finally, researchers at UW-Madison have suggested a monthly child allowance paid directly to families. Some of these proposals have other components as well, either removing some existing supports or restructuring those programs. But for my purposes, I want to make a rough model of what impact implementing these policies might have if we didn’t make any other changes.

The chart below summarizes each proposal, has calculated out a rough estimate of how much it might cost to implement, then re-packages that cost as if the proposal on offer were actually a monthly allowance given to parents for the first 6 years of a child’s life. In other words, I’ve taken the total dollar amount in question, and applied it to an imaginary “child allowance” policy, in order to enable easy comparison, and because child allowances have the most extensive academic literature surrounding them.

With some basic estimates from these programs in hand, we can then compare to the estimates available for the impact of financial incentives on fertility.

As shown in the figure above, all of the proposed policies manage to at least get a participation award: they’re within the realm of policies that, using benchmarks from foreign countries, might boost fertility to replacement rates in the short run. Even Senator Marco Rubio’s comparatively diminutive tax credit proposal is bigger than necessary to boost short-run fertility to replacement if you use the very optimistic estimates from the UK or Australia as your baseline. And several policies on offer from left-leaning groups are large enough that they really ought to push fertility to near-replacement levels if the literature showing a fertility impact from financial incentives is true.

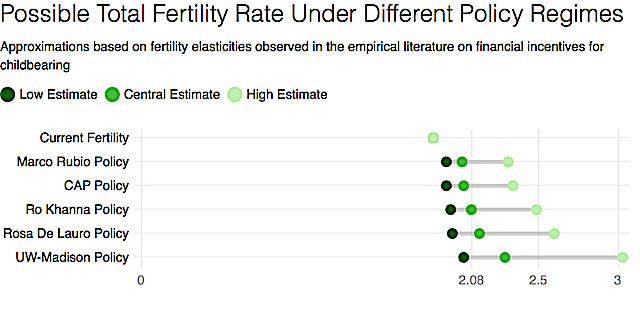

But alas, boosting completed fertility is much, much harder. The two graphs below show a plausible range of effects for each policy on current and completed fertility. That is, these graphs answer the question: if the policies in question had the same effects as other policies that have been studied in the papers that do show impacts on fertility, what would happen to American fertility? Would it end up at, above, or still below replacement rates?

It’s clear from this figure that all of these policies offer a near-guarantee of boosting short-run fertility by some amount if optimistic academic literature is to be believed, but the possible upper limit to that increase is uncertain. At least three of these policies show a central estimate of total fertility rising to replacement levels or above, and, if you believe the most optimistic forecasts, they could all boost short-run fertility above replacement. However, we probably shouldn’t believe those forecasts, as they’re anomalously high for the existing academic literature. Plus, for simplicity I’m treating all of these as monthly cash grants, where effects are most clearly demonstrated. For Congressman Khanna’s policy, for example, this choice overstates any likely pro-fertility impact, as working tax credits do not have as well-demonstrated fertility impacts as cash grants.

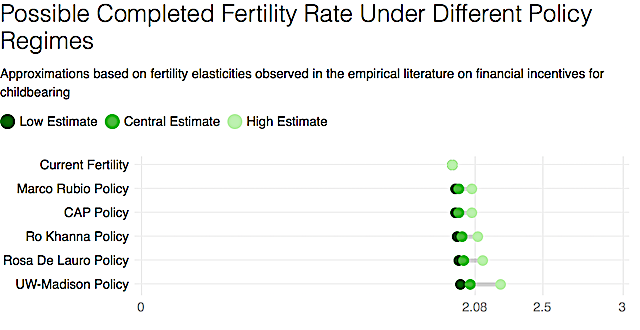

But when we look at completed fertility, which is what really matters for determining if women will be able to achieve the family life they envision, likely outcomes are even less hopeful (see figure below).

The central estimate for completed fertility doesn’t reach replacement rate for any of these policies. Even under a very optimistic scenario, several policies fall short of replacement. In other words, the very biggest policy proposals still don’t give what I would call a better-than-even chance of boosting fertility to replacement levels in the long run, and none of them get even close to helping women achieve their stated level of desired fertility. That is to say, the most generous “pro-family” policies on offer will still probably fall woefully short of helping families actually obtain their goals. And remember, this is assuming that the impact sizes measured in the academic literature are correct, when, in fact, many more skeptical papers suggest there may be no effect at all.

All of the policies discussed in this article would probably do something. Even the smallest of these pro-family policies would help families more than the status quo and would be likely to result in more women getting closer to having as many kids as they want. But the point is that our politicians have critically underestimated the scale of the fertility collapse in the United States, along with the price tag they’ll face if they want to fix it using financial incentives.

Lyman Stone is an economist who blogs at In a State of Migration, and a proud Kentuckian. Lyman also works as an agricultural economist at USDA. His views are not endorsed by, supported by, or in any way reflective of the US government.

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.