Highlights

- The likelihood that your home has a child in it is falling—regardless of whether you live in a principal city, one of its suburbs or exurbs, or in the country. Post This

- We are right to worry about how to make cities more friendly to families, but we must also realize that these problems are not unique to urban life. Post This

After decades of decline, the ongoing renaissance of urban life in many American cities has been accompanied by skyrocketing rents, gentrification tensions, and “not-in-my-backyard” fights over development projects. Seemingly caught in the crossfire? Kids.

Last October, Axios featured a clever data visualization showing the noticeable decline in the share of households with children in the largest U.S. cities. The hottest metropolises—the Bay Area, Boston, the Washington, D.C., metro area—seem to be the ones with the fewest number of children present. “Our great American cities, from New York and Chicago to Los Angeles and Seattle, are evolving into playgrounds for the rich…[while] the middle-class family has been pushed to the margins,” wrote Joel Kotkin, one of the fiercest critics of contemporary urbanism.

What’s wrong with this narrative? It’s not just U.S. cities that are seeing a decline in households with children—it’s everywhere.

Yes, cities have seen a decline in the number of children—there are, famously, as many dogs as children in San Francisco, and the fraction of households in major cities with children is down 7% from 2009 (32.3 to 30.1%).

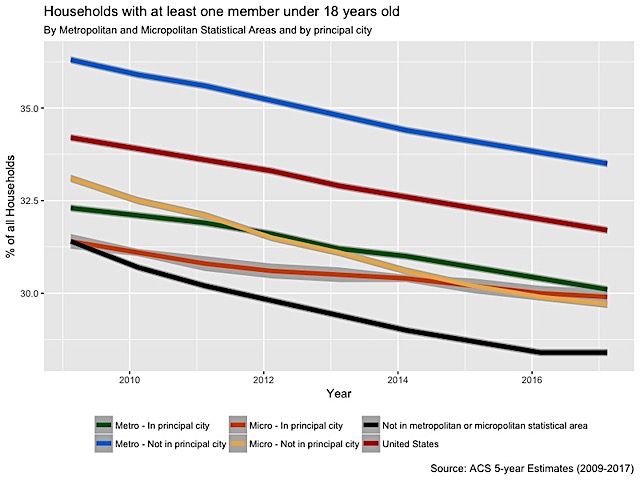

But the decline in childrearing is not limited to urban centers. Let’s look at data from the American Community Survey, which breaks out households made up of married-couple families with a child under 18 at home according to the type of area they live in—in Metropolitan Statistical Areas (around an urban cluster of 50,000 or more), in Micropolitan Statistical Areas (an area of 10,000 – 50,000 people), or in rural America. The likelihood that your home has a child in it is falling—regardless of whether you live in a principal city, one of its suburbs or exurbs, or in the country:

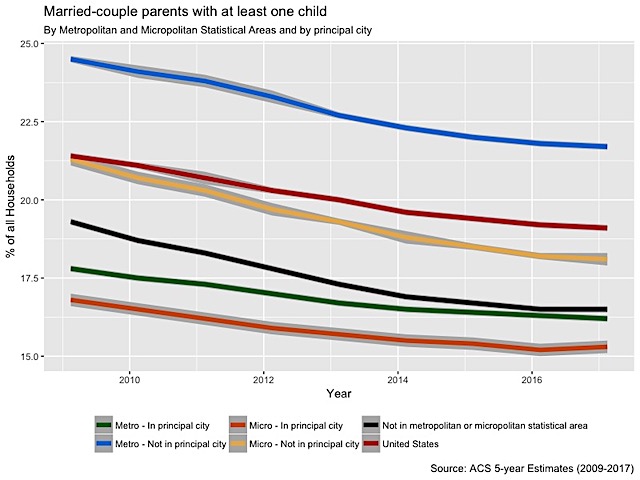

These data start at the Great Recession, so the time-series story we can tell is somewhat limited. Even in this short time frame, all households became less likely to have a child at home as the Millennial generation age out and birth rates continue to fall. For example, in 2017, a family made up of a married-couple with at least one child accounted for 19.1% of all households in the U.S. The dark green line showing households with a child present in metropolitan principal cities (about one-third of the U.S. population) even had a flatter decline than households in micropolitan areas, while the share of households with children in rural America has plummeted, as many of the young leave and the remaining population ages.

The percentage of households in metropolitan principal cities that consisted of a married couple with a child fell by 9% (from 17.8 to 16.2%), less than the drop among households in metropolitan suburbs and exurbs (an 11.4% drop, to 21.7% of all households).

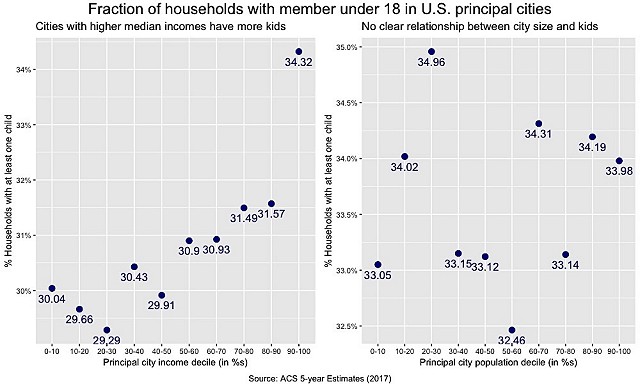

The suburbs continue to be more popular for families with children, and richer on a per capita basis than the city cores they surround, which we see evidence of when we look at the fraction of children present in U.S. cities, broken out by median household income deciles (at left, below.) At right, we see the same categorization, this time by population, indicating that the narrative of our largest cities being especially hostile to families is not necessarily borne out in the data.

Much of this, of course, reflects self-selection. Many couples leave the city for the suburbs upon having a child, preferring the stability of home ownership over renting in the city. But other parents wished they could afford city life with a child, and maybe some city dwellers who would like to have children are less likely to do so in the face of high city rents.

But is it the high cost of rent that is causing families to avoid cities? Or could it be something like the lack of space? Even the hardiest of parents wanting to hack it in the big city might be tempted to reconsider the green fields of suburbia with a 3-year-old in a one-bedroom apartment. Kotkin would argue that “density drives families away from urban cores,” though anecdotes abound of parents committed to making life in the city work for themselves and their children.

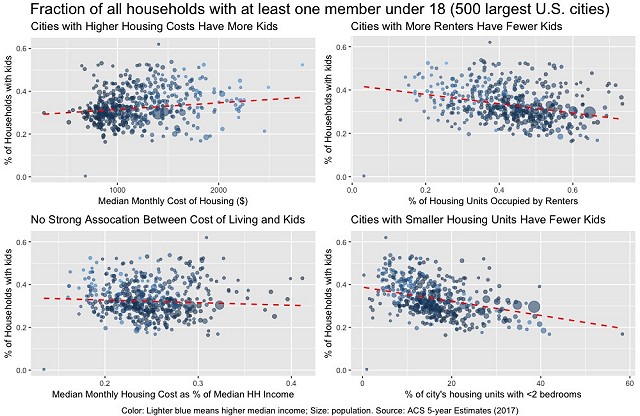

High-demand cities have a higher percentage of housing units with one (or fewer) bedrooms, and they are also more likely to have a higher percentage of residents renting rather than buying. I looked at American Community Survey data on the 500 largest U.S. principal cities by population, a higher percentage of the population renting is associated with fewer children around, and higher rents (not shown) are associated with fewer households with children. At the same time, cities with higher overall monthly housing costs (including rents and mortgage payments) have higher fractions of households with children, indicating the impact of the wealthy, child-rich suburbs.

When we normalize the monthly cost of housing by the median household income, the relationship between the fraction of income spent on housing and children present largely goes away. As seen in the bottom left graph, the fraction of households with children present in a city barely falls, even as larger portions of monthly income go toward paying for a family’s housing. High-income families spend a lower fraction of their income on housing, but overall, the additional cost burden doesn’t lead to dramatically lower percentages of households with children.

The unavoidable truth spelling trouble for young families is that in high-demand urban areas, smaller apartments are more profitable than larger ones. Developers can make more money off of two, 1-bedroom apartments than by using the same physical space to build a unit that can house a family. I’ve criticized “hysterectomy zoning” before, but there’s only so much blame to be allocated to building restrictions and heavy-handed zoning codes that directly prevent family-friendly apartments from being built. Rather, the unfriendliness of urban housing markets to families is partly a function of how in-demand a city is, which is associated with having more housing units with fewer bedrooms.

Cities and suburbs artificially restricting housing supply should reduce those barriers as a matter of reaching a more efficient equilibrium, but the fundamental dynamics of high demand and inelastic supply mean we should not expect that to necessarily translate to more housing that is affordable and appropriate for families. In-demand cities might experience better luck reducing market rents by allowing more housing to be built, whatever the size. Seattle, for example, has seen housing costs stabilize after a decade of skyrocketing rents thanks to a flood of new market-rate housing.

A reminder that this data is looking at all children under 18 in the home, not fertility. As IFS’ own Lyman Stone found last year, increases in housing costs coupled with a higher fraction of renters in cities might be curbing realized fertility. A 2014 study by the Federal Reserve’s Lisa Dettling and University of Maryland economist Melissa Kearney found that a short-term rise in home prices leads to an increase in fertility for people who own a home—but a decline in births among renters. And since more young adults are working in cities today than in prior decades, we might have expected more children to be born in urban centers were it not for those high rents. At the same time, however, households with children are falling in the suburbs, exurbs, or rural America. We are right to worry about how to make cities more friendly to families, but we must also realize that these problems are not unique to urban life.

There’s also an immigration story at play—of the top 100 largest cities in America, 18 of the top 20 cities with the highest percentage of households with families are in heavily-Hispanic portions of California, Texas, and Arizona. The ACS data show that Los Angeles (30.4% of households) and New York City (29.6%), far from being childless, are similarly buoyed, coming in just around the median in this subset.

High rents are a symptom of high demand for hip downtown neighborhoods and may lead young, would-be parents to put off having children. But there are plenty of neighborhoods in America’s cities—especially, but not limited to, those with high immigrant populations—in which children are still seen on a daily basis. At the same time, the streets are quieter than ever in an increasing number of suburbs.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a graduate student at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.