Highlights

Editor’s Note: This post by IFS research director Wendy Wang is the first of three posts in a roundtable on men and women at work that the Institute for Family Studies is hosting this week.*

The Google Memo has stirred up a new flurry of controversy over men and women in the workplace, especially in the technology field. Despite the progress that women have made in most professional fields, certain jobs are still largely occupied by men. For example, 87% of engineers in the U.S. are men. And women’s presence in leadership roles are also rare—only 5% of the CEOs of S&P 500 companies are women.

What factors might account for the gender disparities in tech? Here are five related facts from public opinion surveys and other data sources to consider:

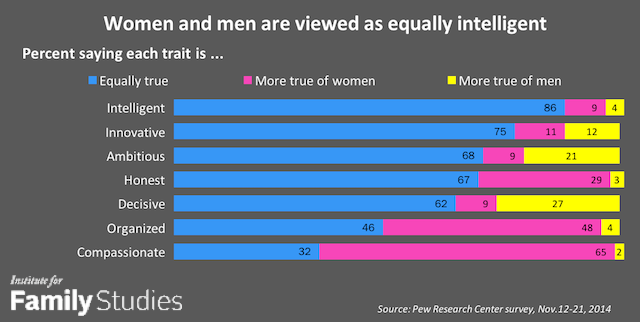

1. On intelligence, women and men are rated equally by the public. A vast majority of the American public (86%) thinks that women are as intelligent as men, if not smarter, according to a Pew Research Center poll. When it comes to special qualities for technological jobs, such as being “innovative,” large shares of both men and women (75%) think that the two genders are equally likely to have that trait. In addition, women have an edge over men in terms of being honest, compassionate, and organized.

2. The public does not agree with the idea that “men are better at math and science than women.” As early as 2005, a Gallup poll shows that 68% of the public thinks men and women have equal abilities in math and science. Among the minority of adults (21%) who believe that men are better at math and science than women, about half say that the reason is biological, and another half feel that it is due to the way society and the educational system treats boys and girls.

3. The public has confidence in women as tech leaders. In the same Pew Research Center poll noted above, about 40% of the public say that, all other things being equal, women and men can do an equally good job when it comes to running a computer software company. But slightly more people (both men and women) say that a man would do a better job than a woman in running tech companies (29%) than the other way around (18%).

4. Despite progress, women have not made major inroads into tech. Women account for about half of the U.S. labor force and have been increasingly moving into previously male-dominated professional fields. According to data compiled by the National Science Foundation, close to half of biological and life scientists (48%) are now women, up from 40% in 2006. However, women’s inroads into tech fields have been slow. The share of women in the mathematical or computer science fields has actually gone down slightly, from 27% in 2006 to 25% in 2015. Moreover, the share of women getting a bachelor’s degree in computer science fell from 23% in 2004 to 18% in 2014.

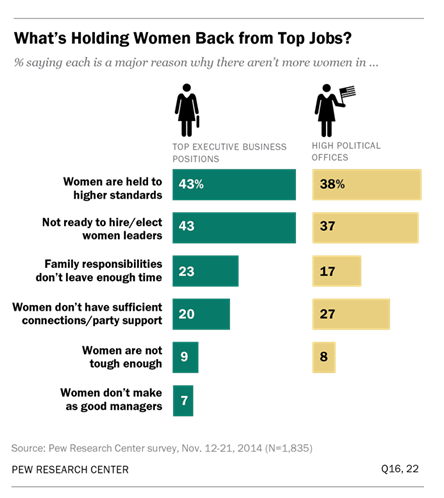

5. When it comes to what’s holding women back, work-family balance is not viewed as the top reason. There is an obvious gap between what the public thinks women could do and what they actually do in the workplace.

Why? According to most Americans, it is not that women need the balance between work and family—only 23% of the public says this is the major reason why women are not taking the top jobs, for example, in the business or tech. Instead, the same Pew poll finds that the public believes the top reason is that women are held to a higher standard than men when seeking to become leaders. Another equally important reason, in the public eye, is that many businesses don’t seem to be ready for women leaders.

Wendy Wang (Ph.D., University of Maryland) is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies and a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center, where she conducted research on marriage, gender, work, and family life in the United States.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.