Highlights

Meaning in life plays a critical role in both mental and physical health. People who view their lives as meaningful are less likely to suffer and more likely to recover from mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety than those who do not view their lives as meaningful. They are also better able to cope with stress, disappointment, and loss and less inclined to abuse drugs and alcohol, as well as desire and attempt suicide. Not surprisingly, then, those who feel meaningful aren’t just psychologically healthier—they also live longer, healthier lives.

Though there are many ways to find and maintain meaning, religious faith is a particularly powerful existential resource for human beings. Indeed, studies show that belief in God and religiosity are associated with the belief that life is meaningful. Religion doesn’t offer the only or even a sure path to meaning. However, it is unwise to ignore the meaning-providing role that faith continues to play in the lives of much of the world’s population, particularly considering the rapid decline in traditional religious beliefs, identifications, and practices in the West.

Beyond the changing religious landscape, recent trends in American family and social life have implications for meaning. Studies reveal that close social and family bonds are vital sources of meaning in life. But compared to generations past, Americans today are waiting longer to get married and have children, having fewer kids, or opting out of marriage and family entirely. These trends don’t appear to simply reflect a reshuffling of how people organize their social lives but instead suggest that we are increasingly less socially connected. Americans today, particularly younger adults, are less trusting of their fellow citizens and less likely to feel that there are people in whom they can confide. Loneliness is on the rise, especially among young adults. And as people spend more time in the digital world of social media, they are often less invested in the face-to-face relationships that best meet social and psychological needs.

With these issues in mind, I set out to explore how modern American men and women—both believers and nonbelievers—think about and experience meaning, and whether there are differences between those who are invested in traditional meaning-providing institutions (i.e., faith and family) and those who are not. To do this, my research team conducted two online surveys of American adult theists and atheists (read the full research findings in more detail here).

In the first survey, we asked roughly 400 people to describe in writing what makes their lives meaningful. This offered a novel approach to studying meaning because we did not orient people towards any particular idea of what makes life meaningful: we let them tell us.

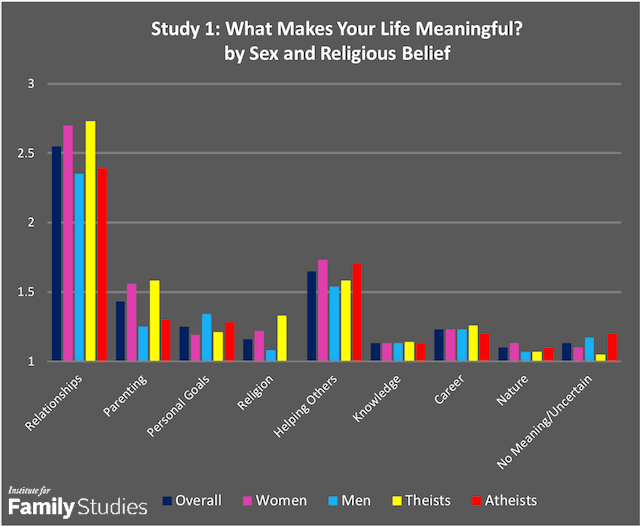

What did we find? First, as shown in the figure below, social relationships and related social themes, such as helping others, emerged as the most prominent sources of meaning for all participants. Men, women, believers, and nonbelievers find meaning through their interpersonal relationships.

When looking at each source of meaning, we observed some statistically significant differences between groups. Theists, compared to atheists, focused more on relationships, parenting, and, not surprisingly, religion. Pointing to the general decline of religion in American life, religion did not stand out as a prominently mentioned source of meaning, even among believers. Also, atheists were more inclined than theists to describe life as having no meaning or to say they felt uncertain about life’s meaning, though this was not a common response.

There were a number of significant differences between the sexes. Women, compared to men, focused more on relationships, parenting, religion, helping others, and nature. Theist women were particularly inclined to focus on parenting as a source of meaning. Males focused more on personal goals/self-improvement.

In the second survey, we recruited around 500 adult participants. Instead of asking them to write about what gives their lives meaning, based on the findings of the first study and other research, we created a list of specific sources of meaning and asked participants to rate the extent to which each source is important to their own sense of meaning in life. In addition, they completed a questionnaire assessing how meaningful they perceive their lives to be. Finally, we asked participants about their marital and parental status.

Again, we found a number of statistically significant differences between groups. Echoing the findings of the first survey, theists rated family, raising children, spirituality, and religion as more important to meaning than atheists, who rated friends as more important.

Marriage appears to matter for what people find meaningful. Compared to single individuals, married individuals rated their partner, family, spirituality, and religion as more important to meaning. Single adults rated self-improvement as more important to meaning. The sex of the participant did not influence these results; however, married and single men and women did differ in the extent to which they viewed careers as important to meaning. Among single people, men and women were very similar in how they viewed the importance of their careers to their sense of meaning. Among married individuals, women rated their careers as less important for meaning than men. Married women also viewed their careers as less important than single women.

Parental status also matters. Compared to non-parents, parents rated their partners, family, raising children, helping others, spirituality, and religion as more important to meaning. The sex of the parent was relevant when it came to the importance of family and raising children. Mothers rated family and raising children as more important to meaning compared to fathers. Women without children were the least inclined to view raising children as important to meaning.

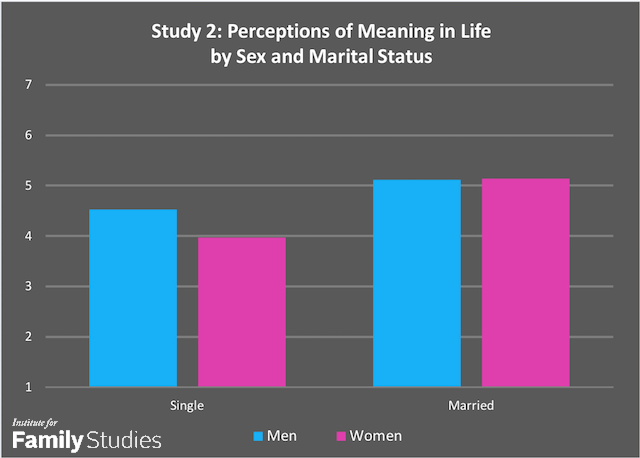

While there are differences in what people find to be important for meaning, what about people's actual perceptions of life as meaningful? Marital and parental status had implications for both men and women. Specifically, married people generally had the meaning advantage over other groups, and single women reported lower meaning than the other groups.

A similar pattern emerged involving parental status. Parents reported higher levels of meaning than people without children, and women without children reported lower meaning than the other groups.

Research has long linked religious faith and close relationships to meaning in life. Of course, these two sources of meaning are often connected as religion has historically provided the institutional (church), social (moral guidelines), behavioral (rituals), and cognitive (beliefs) scaffolding for community and family life. The research described here cannot speak directly to the causes and consequences of current trends in American religious and social life, but it does help inform us about what people view as meaningful and who enjoys the greatest levels of meaning.

As American society continues to change, people may find new ways to maximize meaning. However, the decline of religion and trends related to social and family life should not be ignored as many of the ills that plague our nation may be rooted in the human endeavor to live a life that fulfills the need for meaning.

Read the full research brief, Meaning in Modern America.

Dr. Clay Routledge is a professor of psychology at North Dakota State University. He is a leading expert on the psychology of meaning. You can find out more about his work at www.clayroutledge.com.