Highlights

- Only 14% of Hispanic parents prefer full-time child care for young children, 18% prefer part-time child care, and 62% prefer their kids be cared for by parents or family members. Post This

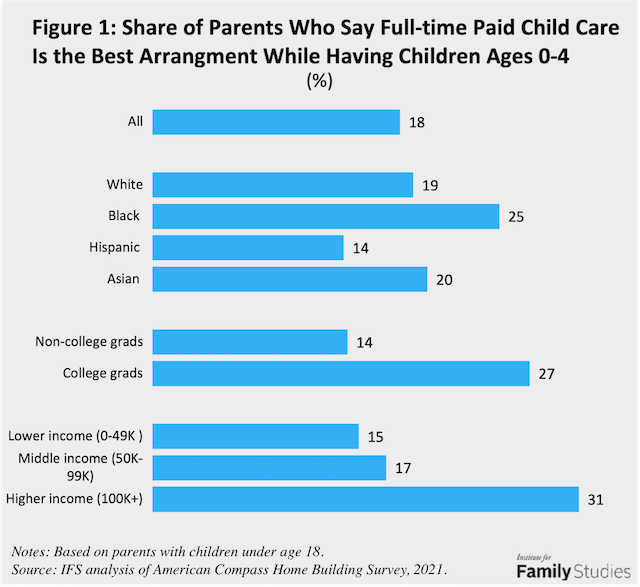

- Only 18% of American parents say the best work-life arrangement for families with kids under age 5 is to have both parents work and use paid full-time child care. Post This

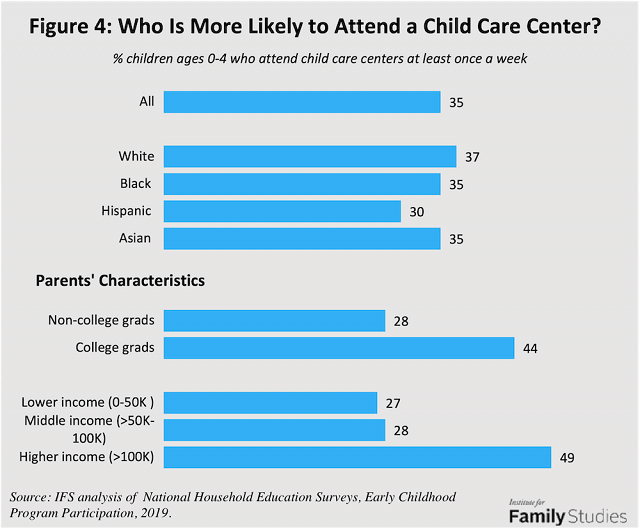

- Educated and affluent parents are about twice as likely to use center-based care compared to poor and working-class parents, and parents without a college degree. Post This

The Biden administration’s American Families Plan includes a proposed $225 billion for child care, aiming to help low-and middle-income families afford the cost of caring for their young children. While the merits of this proposal are up for debate, it is important to situate this issue in the broader context of parents’ preferences on how to best care for their young children and what child care arrangements they currently use. After all, parents are the group most directly impacted by this legislation.

Only 18% of American parents say the best work-life arrangement for families with children under age 5 is to have both parents work and use paid full-time child care. A majority of parents (58%) say they prefer to have their kids at home, either cared for by parents (47%) or a family member (11%). And another 17% say their best arrangement is to have one parent work part time and use paid part-time child care, according to a 2021 survey by American Compass/YouGov.

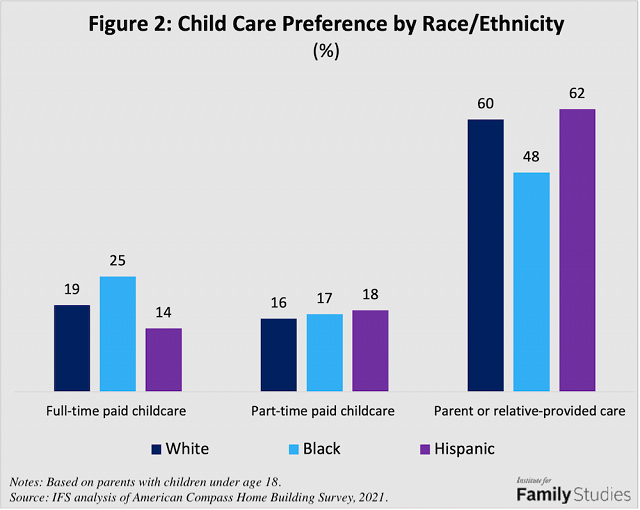

Hispanic parents are the least likely to say they prefer using paid child care full time. Only 14% of Hispanic parents think full-time paid child care is best for their families, compared with 19% of whites, 20% of Asians, and 25% of Black parents.

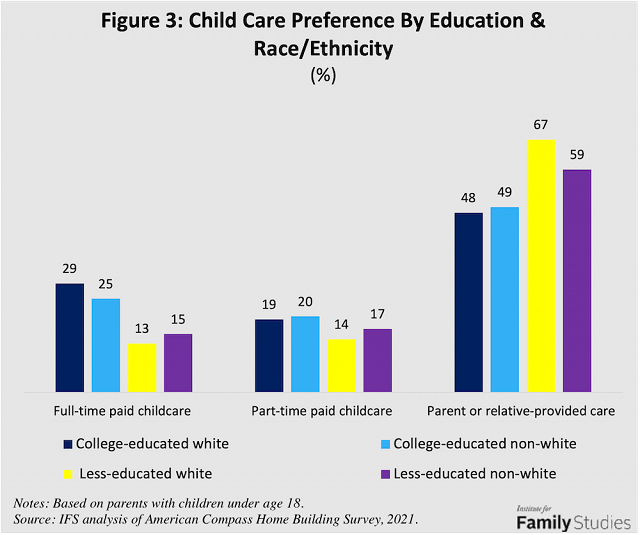

Meanwhile, 27% of college-educated parents and 31% of parents with incomes of $100,000 or more list full-time child care as their ideal arrangement, making them the most likely groups to do so. Nearly 30% of college-educated white parents say that both parents working full-time and using paid child care is the best arrangement for their families. On the other hand, non-college educated white parents are the group least likely to say full-time child care is their preferred arrangement (13%).

When it comes to usage of paid child care, data from the National Center for Education Statistics indicate that Hispanic families with children ages 0-4 are also the least likely to use center-based care. Only 30% of Hispanic parents use center-based care, compared to more than 35% of other parents. Center-based care is also most common among educated and affluent parents, who are about twice as likely to use center-based care compared to poor and working-class parents, and parents who do not have a college degree.

Parents’ Preferences for Child Care

Juggling work and family responsibilities is a challenge for many families today, especially parents with young kids. Even so, only 35% of parents prefer using any kind of paid child care (18% prefer paid full-time and 17% prefer paid part-time child care arrangements), while 58% say that they prefer their kids be cared for by either a parent (47%) or a family member (11%). To be able to do that, these families would have one parent stay at home, or both parents work part time and share care, or rely on other family members, such as grandparents, to care for their kids under age 5.

This may reflect the opportunity cost of working: parents with low earnings potential might rationally observe that paying for care for a young child in order to enter the labor force at a low wage may leave them only slightly better off financially, while likely worse off emotionally. Parents in high-wage jobs, on the other hand, may derive more meaning from work and be more willing to sacrifice income in order to pursue both parenthood and an upwardly aspirational career.

Of the respondents in the American Compass/YouGov survey, Hispanic parents are least likely to prefer using full-time paid child care. Only 14% of Hispanic parents prefer the model of both parents working and using full-time paid child care, 18% prefer part-time child care, and 62% prefer their kids be cared for by parents or family members. In contrast, Black parents are more likely than others to say full-time paid child care is their ideal arrangement. A quarter of Black parents choose their preferred arrangement as both parents working full time and using paid child care full time, while less than half choose parents or other family members caring for their kids as their preferred arrangement.

It is important to note that the survey question was asked of all adults regardless of their marital status and whether they have children or not. We limited the analysis to parents with children under age 18, so their preferences can be compared with observed child care arrangements. Nevertheless, the share of single parents and married parents is about equal when it comes to picking their ideal arrangement as both parents working full time and using full-time paid child care.

Nearly 30% of college-educated white parents prefer full-time paid child care, making them the group most likely to name that arrangement as ideal. In contrast, a full two-thirds of white parents who are not college educated preferred caring for their children themselves or with family, making them least likely to prefer full-time paid child care.

Due to sample size limitations in the American Compass/YouGov survey, we are unable to break down detailed racial and ethnic groups among non-whites by education. But overall, non-white parents, whether college-educated or not, are less likely than white parents to prefer full-time paid child care.

Who Uses Center-based Child Care?

Because of the impact of the pandemic on families and child care providers, the best nationally representative data on child care utilization comes from the 2019 Early Childhood Program Participation Survey (ECPP). In this brief, we use the ECPP, conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics, for estimates on children’s participation in child care centers.

The pattern we found is largely in line with what parents say they prefer. Hispanic kids under age 5 are less likely than others to attend child care centers. Much like the pattern for parents’ preferences, college-educated parents are more likely to send their kids to child care centers than their less-educated peers. About 44% of kids with college-educated parents attend child care centers, compared with 28% of kids with less-educated parents. Moreover, kids from families with incomes of more than $100,000 are much more likely than others to attend child care centers.

Not all children attend child care centers full-time. Many families enroll their children in a part-time, church-run nursery schools, or a twice-a-week day care program, which is counted by the ECPP as “center-based care,” but should be thought of differently. Among the children ages 0-4 who attend child care centers, less than 4 in 10 (38%) spend at least 35 hours per week (full time) there, while others spend fewer hours per week in center-based care. Overall, about 13% of all children ages 0-4 attend a child care center full-time.

In addition to center-based program, the ECPP survey also asks about other nonparental care arrangements, such as care provided by a relative or non-relative (such as a home-based child care provider, nanny, or au pair.) Because many families use a combination of care for their young children, we focus on where children usually spend the most number of hours in any given week—whether with parents, relatives, in non-relative care, or at a child care center.

Using this measure, we find that 30% of American children ages 0-4 are primarily cared for at a child care center, 18% are primarily cared by a relative (e.g. grandparents), 8% are primarily cared by a non-relative, and 42% are primarily cared for by their parents.

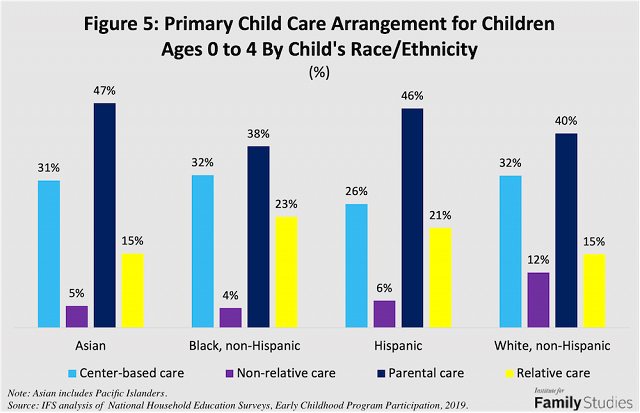

Again, Hispanic children ages 0 to 4 are the least likely to attend child care centers, with only 26% of Hispanic kids primarily cared for at child care centers, compared with about one-third of kids in other racial/ethnic groups. On the other hand, 46% of Hispanic and 47% of Asian children are primarily cared for by parents themselves, making them the groups of children most likely to spend the bulk of their week with their parents.

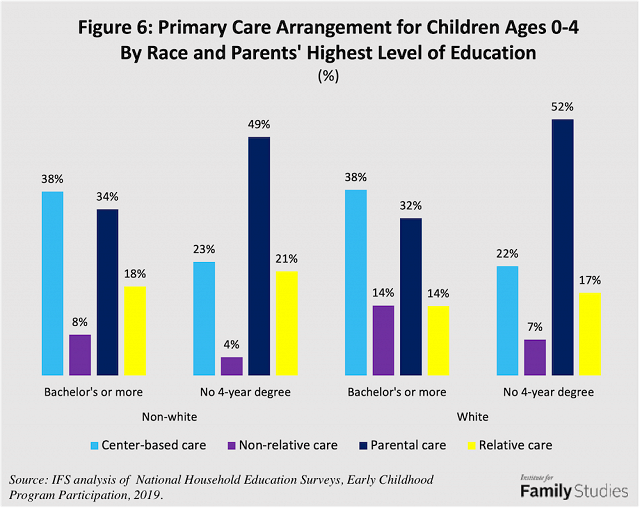

Looking at parents’ education level, we find that both white and non-white young children with college-educated parents are more likely than their peers with less-educated parents to be cared at a child care center. In fact, for kids with college-educated parents, they are more likely to be cared at child care centers than by parents. For children whose parents do not have a college degree, the opposite is true.

For example, among kids of white, non-college educated parents, about half (52%) are cared for primarily by their parents. But among white kids whose parents are college-educated, only 32% of them are primarily cared for by their parents. For white children of college-educated parents, 38% of their children are cared for in a child care center, compared to just 22% for their peers whose parents have less educational attainment. There is very little difference by race, as about 38% of non-white children whose parents are college educated rely primarily on center-based care, compared to 23% of children whose parents do not have a college degree. As explored in the survey of preferences, center-based care is more likely to be the go-to option for parents with higher earnings potential.

In Conclusion

The patterns we document here are partly a consequence of structural as well as cultural factors. The opportunity costs of child care, financially speaking, are larger for lower-income families. Upper-income families, meanwhile, are more likely to benefit financially from center-based child care. This is one reason why more educated and affluent parents are more likely to rely on paid child care.

But there also appears to be a cultural story operating here. Less educated and affluent parents may be more likely to view their profession as a job than as a career. Higher-income parents are more likely to see their job as playing a central role in giving their lives meaning and purpose, a phenomenon dubbed “workism.” This is the idea that work plays a central role in giving our lives meaning, purpose, and even a sense of happiness. Those without a college degree, on the other hand, are less likely to give their career pre-eminence, and seem more likely to find it best to have their young children cared for by parents or kin rather than at a child care center.

This seems to be especially true for Hispanic parents in America. Rather than maximizing each adult’s own career outside the home, among Hispanics, one parent at home caring for children while the other parent works outside the home is an indicator of what can be described as “Hispanic familism.” Hispanic familism emphasizes the family as a single economic and social unit where all household members make some sacrifices for the good of the whole. Hispanic familism is also associated with the belief that children are essential for happiness, which may change the calculus that Hispanic parents have about the relative value of caring for children versus working outside the home. In particular, when it comes to child care, this Institute for Family Studies research brief indicates that Hispanics are more likely than other American parents to prefer that parents or kin take care of young children and to follow through on this orientation by having family members care for their infants and toddlers.

The United States is a deeply pluralistic nation. This pluralism extends to preferences and practices related to child care. This research brief documents noteworthy differences in parental preferences for child care related to ethnicity, education, and income. Policymakers should factor in this pluralism when designing public policies aimed at helping parents care for their young children.

Wendy Wang, Ph.D., is director of research for the Institute for Family Studies. Margarita Mooney Suarez is an Associate Professor at Princeton Theological Seminary and founder and executive director of Scala Foundation. Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a former senior policy advisor to Congress’ Joint Economic Committee.

Appendix:

The American Compass Home Building Survey was conducted by YouGov between January 21 and January 28, 2021, with a representative sample of 2,000 adults aged 18–50 living in the United States. The analysis in this brief is limited to parents with children under age 18 (N=1,097).

Survey question wording: "Which arrangement for paid work and child care do you think is best for your own family while you have children under the age of 5?" OR “If you were to have children in the near future, which arrangement for paid work and child care do you think would be best for your family while your children were under the age of 5?”

Response Categories:

- Both parents work full-time, family uses paid child care full-time.

- One parent works full-time, one parent works part-time, family uses paid child care part-time.

- One parent works full-time, one parent provides child care in home.

- Both parents work part-time and provide child care in home.

- Both parents work, family member (like a grandmother) provides child care.

- Other