Highlights

According to the Census Bureau, the majority of babies born in the U.S. since 2013 have been racial or ethnic minorities. Yet the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reports that the majority of children (52% in 2016) are still born to non-Hispanic white mothers. The discrepancy is a little confusing. Just how close are we to becoming a majority-minority country?

As you might guess, it depends on how you define “minority.” In particular, the apparent disagreement between the Census and the NCHS hinges on how babies with mixed racial-ethnic backgrounds are classified. The NCHS simply reports the background of the mother as listed on the birth certificate, while the Census looks at how parents classify the child on American Community Survey forms.

Such discrepancies and data limitations take on greater significance as Americans grow more likely to enter relationships and have children with people from different demographic backgrounds. In 1967, the year that the Supreme Court struck down laws forbidding interracial marriage, only 3% of new marriages crossed racial lines. In 2015, following a gradual increase, 17% of new marriages crossed racial or ethnic lines.

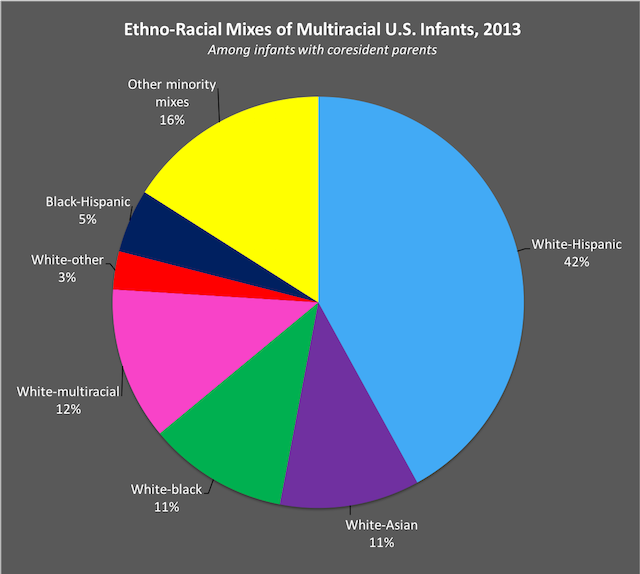

Roughly tracking that increase, unsurprisingly, is the proportion of infants with parents of different backgrounds; it was around 15% in 2013, report Richard Alba, Brenden Beck, and Duygu Basaran Sahin in a new article in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Close to four in five of these children have one white parent and one minority or multiracial parent, most often a Hispanic parent.

Source: 2013 American Community Survey data analyzed in Alba, et al., 2018. "The Rise of Mixed Parentage."

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677 (1):26–38.

But to the Census, all multiracial or multiethnic Americans are minorities. Does that categorization make sense? Not necessarily, say Alba, Beck, and Sahin. In common parlance, “minority” means “nonwhite,” and often connotes a disadvantaged background. But average household income is similar among white children and partly white children—indeed, it is higher among children with one Asian parent and one white parent than those with two white parents—with the exception of children who are partly black. All partly white Americans (partly black ones included) are more likely to marry someone white than marry a member of a minority group; clearly, they are not walled off from white society. Finally, the self-reported background of many multiracial/multi-ethnic Americans varies over time. They may describe themselves as white and Asian on one survey and simply white on another.

All of this implies that the lines between majority and minority, white and nonwhite, are more blurry than eye-catching headlines suggest. And coverage of these demographic trends could carry important implications. Another article published in the same issue of Annals shows that articles with different coverage of America’s demographic future produce distinct emotional reactions in white readers. In one experiment, reading a story that emphasizes how white Americans will become a minority by 2044 produced more anxiety and anger among whites—particularly among Republicans—than a story using a more inclusive definition of whiteness (categorizing partly white Americans as white if that is how they describe themselves) and predicting that whites will remain the majority group in the U.S. That means nuanced coverage of increasing demographic diversity isn’t just desirable for the sake of accuracy. It could also affect race relations and the prevalence of racist discrimination and violence.

Anna Sutherland is a writer and editor living in Michigan.