Highlights

- According to CDC data, lower births on holidays and weekends are closely associated with higher rates of C-sections in the surrounding days. Post This

- In the country of Georgia, the promise of baptism increased fertility substantially, and, combined with increases in child subsidies, fertility has remained above replacement. Post This

- To the extent culture matters, it is less about changing the desire for children, and more about influencing other norms, behaviors, and assumptions. Post This

With American fertility in freefall, demographers and journalists have been looking for explanations. Many focus on the usual suspects: employment, childcare costs, lack of parental leave, housing costs, etc.

These factors do matter. But there’s another set of factors many analysts struggle to wrestle with: culture. The cultural question has grown in prominence as fertility continues to decline amid an extended economic boom. Politics has had a role in amplifying the debate as well: in a now widely-discussed monologue, Fox News host Tucker Carlson bemoaned the state of the American working class, focusing particularly on the inability of ordinary Americans to form families.

So, does culture matter?

Short-Run Cultural Effects Are Easy to Spot

The first trick is to define “culture.” For my purposes, culture is any set of beliefs, norms, or behaviors people have that do not seem to be strictly tied to discernible material interests.

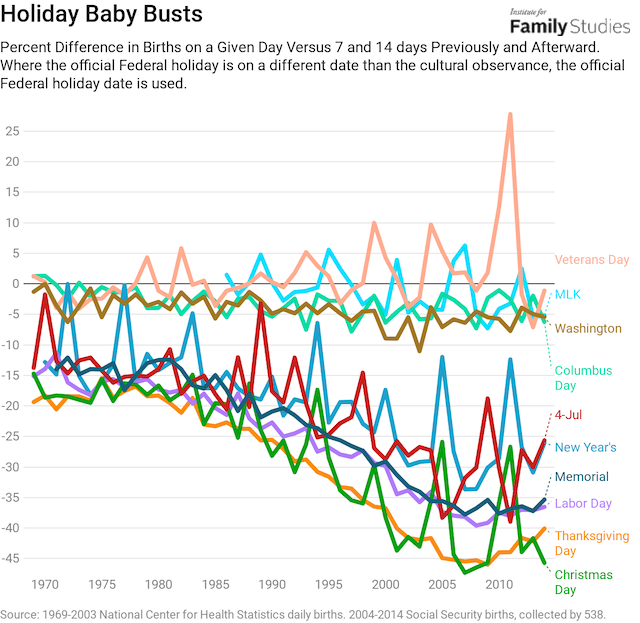

Take holidays as an example. The United States has many holidays and observances. It turns out, people tend to avoid holiday birthdays. The graph below shows the percentage change in births on a given day versus 7 and 14 days before and previously.

As you can see, births are lesson common during the holidays. Nobody wants to mess up their social schedule or waste their vacation days by having a baby on Christmas Day. According to CDC data, lower births on holidays and weekends are closely associated with higher rates of C-sections in the surrounding days, so this really is about parents avoiding holiday births intentionally.

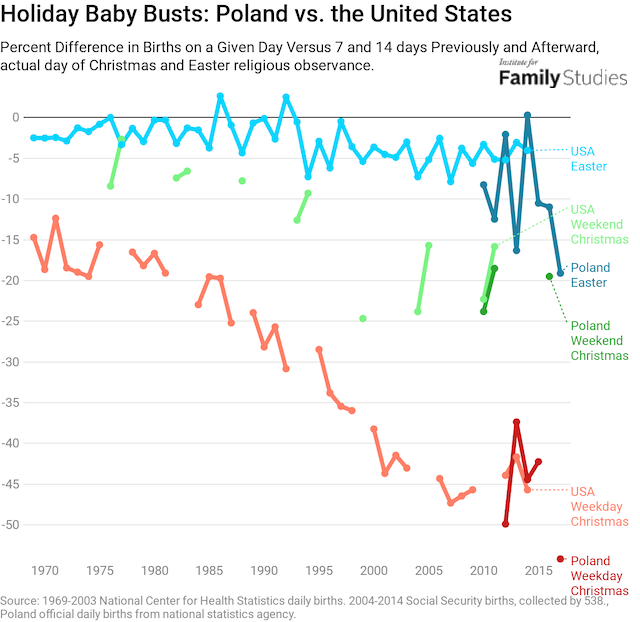

Things are different in other cultures. The graph below shows the daily birth difference around Easter, Christmas when it falls on a weekday, and Christmas when it falls on a weekend, in Poland and the United States. I use Poland because it has a similar religious background as the U.S. (Christianity), but generally of a more liturgical bent, and with greater uniformity (overwhelmingly Catholic).

As the figure illustrates, the U.S. and Poland have virtually identical hits to births on Christmas day. Both American and Polish parents seem to avoid having a Christmas baby, perhaps because, in both countries, there are very large Christmas festivities.

But the two countries show a divergence on Easter. In the U.S., births are only a little bit lower on Easter than the Sundays 1 and 2 weeks before; the effect is barely large enough to register. But in Poland, the effect of Easter Sunday is almost as large as the effect of a weekend Christmas on reducing daily births!

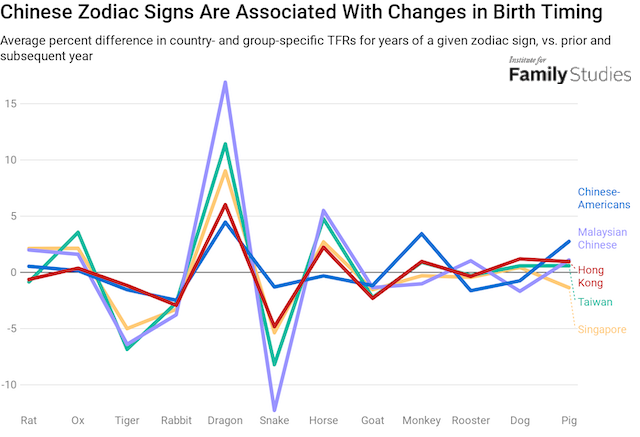

In other societies, radically different effects show up. For example, lucky and unlucky years on the Chinese Zodiac influence the timing of births. The graph below shows the average difference in total fertility rates between a year of a given zodiac sign and the year before and after it for a range of ethnically Chinese populations for which good-quality data is available.

The most reliable effects are a big bump in births in Dragon years, as well as a decline in Tiger years. But the point here is not to do a deep analysis of Chinese Zodiac signs, but just to observe that, from all appearance, arbitrary cultural beliefs about lucky and unlucky years do seem to influence fertility.

It's easy to find more examples of this kind of thing around the world. I found at least four holiday-fertility effects documented in a brief search, including Christmas and summer holidays in the Czech Republic, Ramadan observance among Muslims in Israel, New Year’s festivities in France, and the Ghost Month in Taiwan. All have all been shown to have a major role in shaping the timing of births.

So, do seemingly-arbitrary, non-economic factors related to beliefs and values have an influence on fertility? Yes, at least as far as timing is concerned. But does it influence the bigger question: how many kids people have? Research on fertility timing and level among immigrants and their children in the United States and France suggests that the extent to which culture matters for fertility depends on the economic costs of the culturally-prescribed behavior: shifting timing by a few days or months may be a relatively lower cost than shifting fertility completion, so it isn’t clear that these short-run impacts will show up in the long run.

Culture Matters in the Long Run

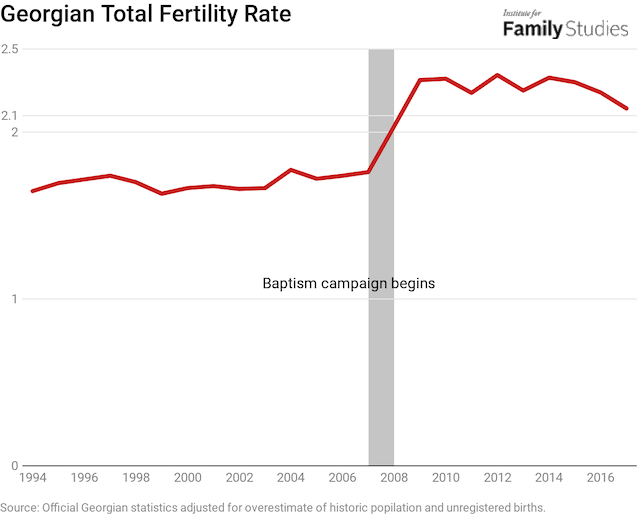

One of my favorite examples of “how culture matters” is documented in another article I’ve written here at IFS. In 2007, in response to a low birth rate, the enormously popular leader of the Georgian Orthodox Church, Patriach Ilia II, announced that he would personally baptize any third or higher parity child. This had a very simple effect: Georgian women had more babies, especially higher-parity babies. This effect wasn’t driven by economic factors, wasn’t duplicated in other Soviet countries or regional neighbors with a similar pre-2007 fertility trend, and does appear to have been concentrated among Georgian Orthodox believers.

As you can see, the promise of baptism increased fertility substantially, and, combined with increases in child subsidies, fertility has remained above replacement. It is a near-surety that this effect, having now endured for a decade, and being targeted on higher-parity children, will result in higher completed fertility for Georgian women. In other words, a specific, arbitrary cultural decision (Patriach Ilia II’s promise of personal baptism for third children) yielded a durable change in fertility behavior.

But Georgia may be unique in this regard. Georgia is a 90% Orthodox country, and among Orthodox countries, one of the most devout. Can these results be extrapolated to bigger, diverse countries?

Some studies suggest that the answer may be yes. A study of American fertility demonstrated that higher viewership in an area of the shows 16 and Pregnant, Teen Mom, and Teen Mom 2 resulted in lower teen pregnancy, associated with increased Twitter activity and Google searches related to birth control and abortion. There have been criticisms of this study, but, overall, its findings have held up pretty well. As I’ve shown elsewhere, reduced young pregnancies are not being compensated for by higher birth rates at older ages these days, and thus this reduction in teen births can be viewed as a durable reduction in the birth rate. In other words, even in a diverse, pluralist society like the United States, cultural effects seem to matter.

Similar effects of entertainment on fertility have been demonstrated in other contexts. In Brazil, the childbearing behaviors of popular soap opera characters altered the fertility behavior of viewers, including significant differences in how children were named: a durable, not temporary, effect. Around the world, higher prevalence of television viewership is associated with lower sexual frequency, which might reduce fertility; and of course in the United States, the rise of smart phones has been identified as a possible driver of lower American sexual frequency. These are not inevitable social or cultural choices. Societies have wide variety in TV viewership even in similar-income countries. TV show writers can alter how many kids their characters have and their attitudes toward those kids. Seemingly arbitrary societal choices about how to present families do actually matter for fertility.

Traditional fertility norms can be passed down by families for generations. Research by Bastien Chabe-Ferret (the same author cited earlier who modeled the culture/economic cost trade-off) shows that cultural norms can be inherited and conditioned. Controlling for socioeconomic status, African-American women in America born in states with higher historic African-American fertility completion are themselves more likely to have more kids. In other words, higher fertility is transmitted across generations and reinforced by certain environments. The strength of the association gets weaker the more educated a woman becomes, but it never vanishes entirely.

The same author studied fertility behavior among the Roma minority in Serbia and found that Roma living in homogenous enclaves had higher birth rates than those living around more ethnically different neighbors. In other words, living in communities that support traditional family norms makes it less costly for people to pursue and achieve those family norms. No surprise! This is related to my argument that one way to boost American fertility is to increase our voluntary, community-based support for parenting. Finally, Dr. Chabe-Ferret, using data on minorities from Indonesia, shows that the demographic position of a group can alter fertility: minority and threatened groups do actually appear to use the “weapon of the womb” to increase political power. Higher fertility rates among minorities may be a political tool. But crucially, while he looks at minorities, the same logic should apply to threatened majorities: status threat to a group can cause them to invest in a long-term strategy for political dominance—higher fertility. The specific effects here are perhaps less interesting than the wider implication that fertility rates respond to the social and cultural position of a group or an individual. In other words: culture matters.

Culture Matters in America

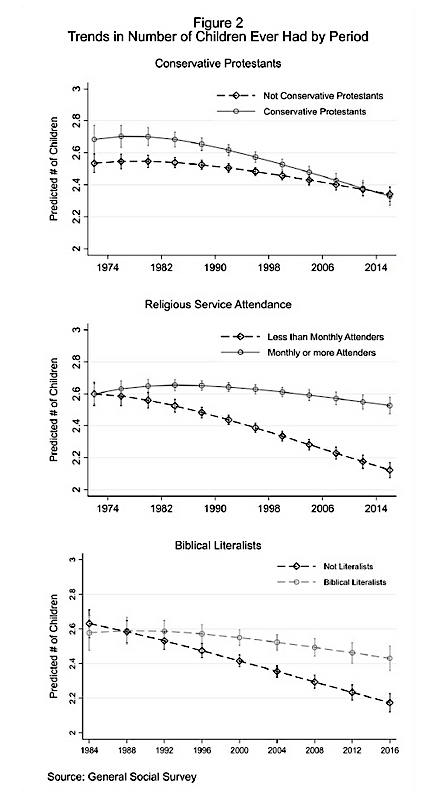

This kind of argument can be proven very easily in data for America as well. The General Social Survey (GSS) asks people about a wide range of cultural factors, as well as some questions about fertility. A recent paper by Samuel Perry using GSS data showed that, while fertility is declining for all Americans, it has by far declined the least among religiously-devout Americans. That is, the effect of regular church attendance on fertility, measured as the gap in completed childbearing between regular service attenders and those who do not regularly attend church is large (about 0.4 kids per woman!) and growing (see figure below).

This paper, of course, headlines its findings by showing that denominational affiliation with a conservative Protestant group no longer predicts high fertility. Being a member of the Southern Baptist Convention or the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod doesn’t predict fertility well anymore. But church attendance does predict fertility, and the effect is getting stronger.

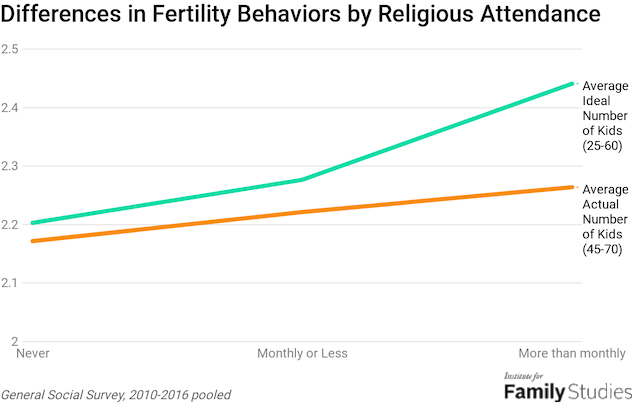

Looking at GSS data from 2010 to 2016, we can see to what extent religion predicts exceptional fertility behavior. The graph below shows how many children women say is ideal, broken out by the frequency of religious attendance, as well as the number of kids that women ages 45-70 actually had, by religious attendance.

Because I use far fewer controls than in the study described above, my measured effects are smaller. But the basic outcome is still the same: religious women want more kids, and they do end up having more kids.

The point is, religious people have more kids, and a big part of the driver for that is religious people wanting to have more kids. Crucially, if I restrict my sample to women ages 20 to 35, religious people don’t have more kids: religious attenders don’t show higher rates of young or teen births, just higher completed births.

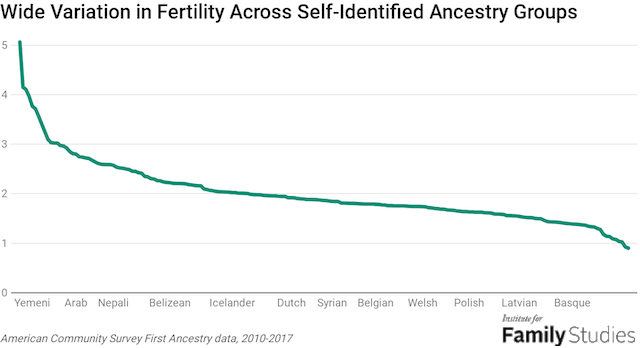

Religion isn’t the only American cultural pattern that seems to matter. The graph below shows the total fertility rate by self-reported ancestry groups with at least 20,000 people, from 2010-2017, in the American Community Survey.

As can be seen, self-reported ancestries have huge variation in fertility rates. But perhaps just as importantly, reporting an ancestry at all is predictive of higher fertility. A woman in the average ancestry group turning 15 between 2010 and 2017 could expect to have about 2 children over her life if birth rates remain stable. But among women who did not report any ancestry, it’s just 1.74 children. In other words, many ancestry groups yield higher or lower fertility, but, on average, simply identifying with any ancestral community is associated with higher age-controlled birth rates. I don’t have a way to prove causality here, but it makes sense that self-identifying as being connected to some intergenerational ancestral heritage could be a good predictor of having an interest in perpetuating that heritage.

Culture and the Working Class

But returning to the question that inspired this post: might the poor state of family formation in America’s working class be somehow related to their cultural norms? Certainly many conservative writers have argued as much. One of the nation’s bestselling recent books, Hillbilly Elegy was a book-length accounting of the essentially cultural malaise afflicting the white working class. But is it possible to point to discrete social norms that may be inhibiting family formation?

The obvious candidate for such a norm is our attitudes about family income. Previous research has suggested that negative shocks to male income may reduce marriage rates, while negative shocks to female income may increase marriage rates. The presumed channel for this effect is that men and women both tend to have a revealed preference for a male-breadwinner family model.

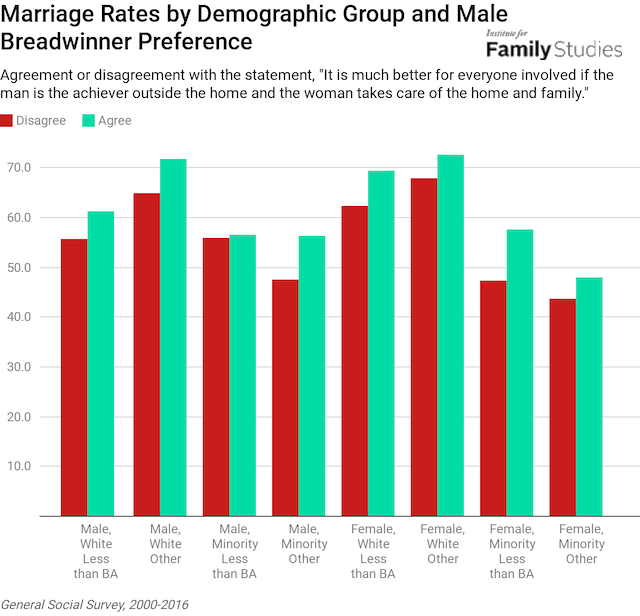

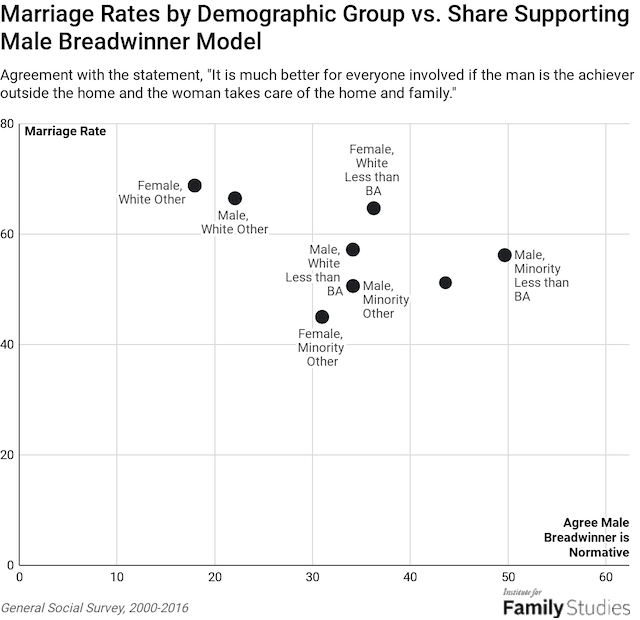

The GSS asks respondents to agree or disagree with the statement that “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Below, I show the share who are married, by question response and demographic group.

As you can see, people who agree to some extent with the male-breadwinner model are more likely to be married, even among the working class. This is striking because male working-class incomes have shown far weaker growth over the last decade or two than female working-class incomes. Thus, within demographic groups, greater belief in a male-breadwinner model is associated with higher marriage rates.

But the story gets more complicated.

When we look at the correlation between support for the male-breadwinner model and marriage rates across demographic groups rather than within them, the association reverses. In demographic categories with greater belief in the male breadwinner model, we observe lower marriage rates. Thus, while the people within a group who tend to get married tend to be the ones who believe in the male-breadwinner model, having more of those type of people in the group is not predictive of higher group marriage rates.

Precisely this kind of analysis has led some researchers to conclude that the path to greater family stability, more marriage, and more fertility is through more gender-egalitarian values. This claim that “Feminism is the new natalism,” that is, that promoting greater gender equality may increase birth rates, is worth taking seriously, given that groups with more belief in the male-breadwinner model have lower marriage rates. Plus, a cultural change towards more egalitarian values could probably be engineered through a variety of policies.

However, recent research ultimately discredits the idea that more feminism is the solution for families: shifts toward more egalitarian values have not been associated with any fertility increase anywhere in the world. Whatever cultural change could produce higher fertility, it won’t just be more progressivism.

I don’t have the answer today about whether there is a specific set of cultural norms or values among working-class Americans that drives weak family formation. It does seem like cultural beliefs are associated with different outcomes, which suggests there is some effect happening, but teasing it out is extremely challenging. For today, it’s enough to simply show that cultural differences probably do yield differences in key family outcomes.

The problem in America isn’t that people don’t want kids, it’s that they face barriers to achieving their desires. Thus, to the extent culture matters, it is less about changing the desire for children, and more about influencing other norms, behaviors, and assumptions.

Can We Change the Culture?

Culture matters. It is easy to find cases where cultural values, or even shocks to cultural expectations, seem to explain a large amount of variation in births or marriages. That raises a big question: can we change the culture, and thus change fertility? There have been attempts to do so, such as federal efforts to encourage marriage. And, while their advocates say they’re successful, they have faced a lot of criticism on effectiveness grounds, as well. Efforts by East Asian countries to encourage procreation through cultural engineering have not worked well. Lecturing people about what they should do in the bedroom probably isn’t very effective. Plus, in a pluralist society like the United States, direct attempts at cultural engineering are likely to be resisted by the public.

And while many studies have shown examples of mass media and entertainment inducing lower fertility, nobody has yet found a case where it induced higherfertility. It’s possible there just isn’t demand for a TV show with pro-natal themes, however subtle. Even if we knew what message would be effective at changing fertility, it isn’t clear how it could be effectively communicated. My review of data on working-class Americans suggests that we don’t even really know what the cultural problem is.

To add more confusion, the specific type of cultural change America would need to increase fertility may not even be about babies! American women continue to report relatively high desired or intended childbearing. The problem in America isn’t that people don’t want kids, it’s that they face barriers to achieving their desires. Thus, to the extent culture matters, it is less about changing the desire for children, and more about influencing other norms, behaviors, and assumptions.

That said, there is at least one place where cultural choices could matter a lot: education, and especially sex and family education. As I’ve written elsewhere, abundant research has shown two key empirical facts: first, that men and women have a low degree of knowledge about fertility, and systematically underestimate their likelihood of having difficulty becoming pregnant or having children; second, that informing men and women about scientific facts of fertility (especially how rapidly biological potential declines in the late 20s) alters their stated preferences for when to have kids. In other words, the battle over American sex ed curriculum shouldn’t just be about contraception or abstinence: it should include an effort to include science-based fertility education. Women should be informed early in their childbearing years about their actual odds of being married at a given age, their actual likelihood of having a certain number of kids by a certain age, and the difficulties and costs associated with highly delayed childbearing. From middle school to the end of educational years, school counselors, nurses, and sex and family education teachers should include factual information about fertility in the curriculum.

Such a policy change is unlikely to radically alter American fertility. But it would be a step towards better informing young Americans about how to achieve their desired fertility.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.