Highlights

- More adults today between the ages of 18 and 44 have ever cohabited than have ever been married. Post This

- Living together before marriage is associated with lower marital quality and less stability. Post This

- Despite the increase in cohabitation, these relationships still don’t look like marriage when it comes to commitment and longevity. Post This

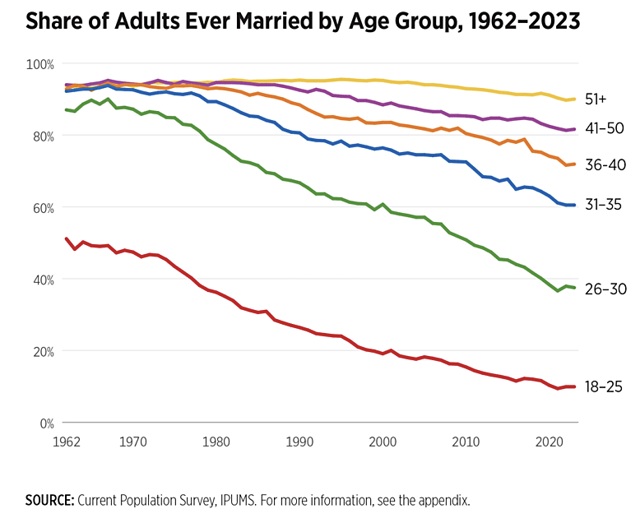

Marriage rates continue to decline, with every succeeding generation seeing lower marriage rates than the previous one. In a new report by Delano Squires and myself, Crossroads: American Family Life at the Intersection of Tradition and Modernity, we note that marriage used to be a common part of young adulthood, but that is no longer the case. Given the trends, researchers project that roughly one-third of Gen Zers will have never married by age 45 and may never marry at all.

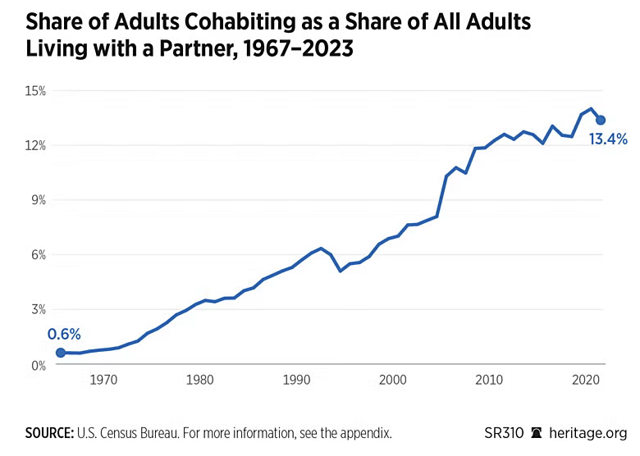

But is part of the reason for the decline in marriage because more couples are just opting to live together instead of getting married? And is living together outside of marriage similar in stability and quality to marriage?

Cohabitation has certainly become much more common, as the following chart from our report illustrates. In 1967, fewer than 1% of all people residing with a partner were unmarried, while in 2023 that number had grown to more than 13 percent. More adults today between the ages of 18 and 44 have ever cohabited than have ever been married.

Still, the overall share of American adults currently unpartnered—neither married nor cohabiting—has increased during the last two decades (although the number of adults who were married or cohabiting went up slightly in 2023). So, the increase in cohabitation hasn’t made up for the decrease in marriage.

Despite the increase in cohabitation, these relationships still don’t look like marriage when it comes to commitment and longevity. One reason is that most people enter cohabiting relationships without clear plans for the future of their relationship rather than making a clear decision to live together (let alone with formal plans to wed). And it is still uncommon for people to remain in a cohabiting relationship for more than a handful of years. Only about 6% of cohabiting relationships that have not transitioned to marriage are still intact at 10 years, among adults born in the 1980s. Among their parents’ generation, it wasn’t much different, with only 3% of cohabiting relationships still together at 10 years. (In contrast, about three quarters of first marriages are still intact at 10 years.)

While in the short-term people are spending more time in cohabiting relationships than they used to, fewer cohabiting relationships actually transition to marriage. Among adults born in the 1950s who cohabited, 23% of relationships transitioned to marriage within one year, compared to just 12% transitioning to marriage among cohabiting adults born in the 1980s.

Rather than people using cohabitation as de facto marriage, for many it has become another step in the dating process.

The downside of longer cohabiting relationships that do not transition to marriage is that men and women are reducing their opportunities for finding a relationship that could lead to matrimony. The rise of cohabitation is likely contributing to the decline in marriage, as people spend more time in long-term dating relationships that increasingly fail to transition to marriage. For cohabiting couples who do marry, living together before marriage is still associated with lower marital quality and poorer stability.

Increased cohabitation also presents problems for children. Cohabiting couples frequently have children together, or bring children into the relationship from previous unions, but because their relationships are far less stable than marriage, children often see their parents break up. More than a third of cohabiting couples have a child together, and another 19% have children in the home from one of the partner’s previous relationships.

Despite the downsides of cohabitation, most Americans are unaware of its associated problems. About three-quarters of high school seniors agree that cohabitation is a good testing ground for marriage, and roughly two-thirds of adults live together before getting married.

To help increase their likelihood for a happy marriage, it is important that young adults understand the risks associated with this increasingly popular relationship arrangement. For example, high schoolers are often taught about the risks of dropping out of school or about the health problems associated with smoking and using illicit drugs. They should also be taught what the research says about cohabitation. Schools can also equip students with other relationship knowledge and skills that can prepare them for healthy marriages in adulthood.

Churches, colleges, businesses, community organizations, and the media should also provide information and education to young adults, as well as to adults at other stages of life, about how to build healthy marriages, including research about cohabitation and how to really improve the likelihood of a successful marriage. All states have funding that can be used for healthy marriage and relationship education, yet they often put it towards other uses, neglecting the importance of marriage.

A society that fosters healthy relationships not only helps create stronger communities, it also helps people achieve one of the most significant factors for human well-being: a healthy, stable marriage.

Rachel Sheffield is a Research Fellow in The Heritage Foundation’s Center for Health and Welfare Policy.