Highlights

- Nearly 60% of U.S. adults believe that cohabiting parenthood is equal to married parenthood. Widespread practice of this belief may result in a disadvantaged life for generations of American children. Post This

- Grown children of cohabiting parents likely have less secure attachments and are more likely to engage in cohabitation themselves and to face the same socioeconomic disadvantages they experienced as a child. Post This

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, proposed an elegantly simple definition of a healthy life: the ability to love and work. As a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, I see hundreds of patients each year who experience difficulties doing just this. It begs the questions: Why? Where do these difficulties come from? And, how do we help people overcome them?

The therapists’ cliché line, “tell me about your childhood,” often reveals the answer to such questions. The dynamics of our childhood relationships are often recreated in our adult lives (a phenomenon referred to as intergenerational repetition). For example, it is not uncommon for a previously-abused child to find themselves in an abusive relationship as an adult. This is also why children who grow up with married parents are more likely to remain married themselves, and why children who grow up with divorced parents are more likely to experience divorce as adults. And, not surprisingly, children of unwed parents are more likely to become unwed, possibly cohabiting, parents themselves. Whether consciously or unconsciously, people seek relationship dynamics that are familiar to them, even when they are dangerous or destructive.

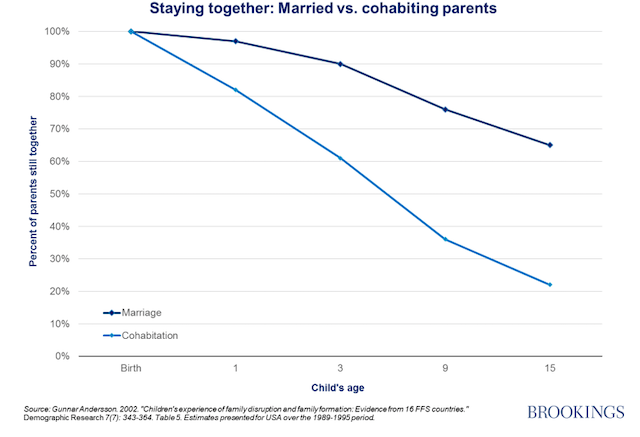

According to a Pew Research Center survey, nearly 60% of U.S. adults now feel that “couples who are living together but not married can raise children just as well as married couples.'' Current evidence, however, does not support this claim. Research shows that two-thirds of cohabiting parents will have separated by their child’s twelfth birthday, compared to only one-quarter of married parents (see figure below).

To understand the implications, it is necessary to explore both attachment theory and the actual outcomes for such children.

Attachment Theory:

Psychiatrist John Bowlby defined attachment as a strong emotional tie to a specific person (or persons) that promotes a young child’s sense of security. This tie demands more than just the provision of food, clothing, and shelter for a child; it requires an emotional connection. Threats to the availability of such connection can produce fear, anger, and sadness in the child—emotions that, if unattended, may persist into adulthood.

Psychologist Mary Ainsworth took Bowlby’s work one step further. She outlined four primary types of childhood attachment (secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent/resistant, and insecure-disorganized/disoriented) that resulted largely from the physical and emotional availability of the parents toward the child. What’s more is that, barring significant life changes, the attachment style an individual develops in childhood tends to persist into adulthood and may be amplified by the experience of parenthood (thus setting the stage for transmission of attachment styles across generations). In short, parents are likely to parent how they were parented, and love how they were loved.

Now consider that 2 out of 3 children born to cohabiting parents will experience the loss of at least one major attachment figure before the age of 12. This loss will be accompanied by a period of time where parents experience personal distress and are less available to the child. Following a split, parents may begin dating and will again be less available to the child as they invest in new partners. These new partners may become a significant figure in the child’s life and pose the risk of yet another “loss” if they too leave. These dynamics all increase the likelihood of a child developing an “insecure” attachment style; an attachment style that they will carry into their adult life.

The Outcomes:

Those with an insecure attachment style are more likely to engage in non-committal forms of relationships as adults, such as cohabitation. Within the first year of cohabitation, 19% of women will experience pregnancy, according to the CDC. There are several notable features about Americans who engage in cohabiting parenthood.

Cohabiting parents tend to be younger, have lower levels of educational attainment, and face more economic instability. (For reference, 54% of cohabiting parents have a high school diploma or less, and 16% live below the poverty line. In contrast, 43% of married parents have a bachelor’s degree or greater, and only 8% live below the poverty line). This naturally means there are fewer social and economic resources available to both cohabiting parents and their children. Furthermore, children of cohabiting parents are more likely to experience depression, drug abuse, and drop out of school, compared to children of married parents. These “risk factors” all place strain on the family and increase the likelihood that children will experience negative social, emotional, and psychological outcomes.

There is also a significant racial/ethnic divide amongst cohabiting families—with Blacks and Hispanics being far more likely to cohabitate than their White or Asian counterparts. The decreased frequency of cohabitation amongst White and Asian groups makes it less likely they will experience pregnancy outside of wedlock and face the socioeconomic strains described above. In turn, their children are more likely (but certainly not guaranteed) to have “secure” attachments and less strained interpersonal relationships in their adult lives.

The importance of this divide cannot be overlooked. Psychological research has shown what many of us know instinctively: history tends to repeat itself. Grown children of cohabiting parents likely have less secure attachments, are more likely to engage in cohabitation themselves, and are more likely to face the same socioeconomic disadvantages they experienced as a child. As a result, their children are more likely to experience a similar fate. Thus, an intergenerational cycle of disadvantage is created and reinforced.

By accepting the notion that “couples who are living together but not married can raise children just as well as married couples,” Americans may be embracing a family model that will deepen the economic, racial, and social inequalities of our country.

Francie Broghammer, MD is the Chief Resident in Psychiatry at The University of California Irvine.