Highlights

- In Finland, the most educated women were once the least likely to have kids; now, they’re the most likely, per a new working paper. Post This

- The most educated women in Finland are the most likely to become parents, but once they do, they still don’t have as many kids in total. Post This

- There may be some lessons for the U.S. from Finland when it comes to making women’s education and employment more compatible with family life. But we are very different countries. Post This

Women's education and fertility are often thought of as enemies. Both school itself, and the better-paying jobs it prepares one for, can make it harder to prioritize having children. Here in the U.S., women with no high-school diploma have roughly twice the fertility of women with an associate’s degree or more.

But has Finland flipped the script? A new working paper, released through the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, raises the possibility but leaves much unclear.

The Basic Trendlines

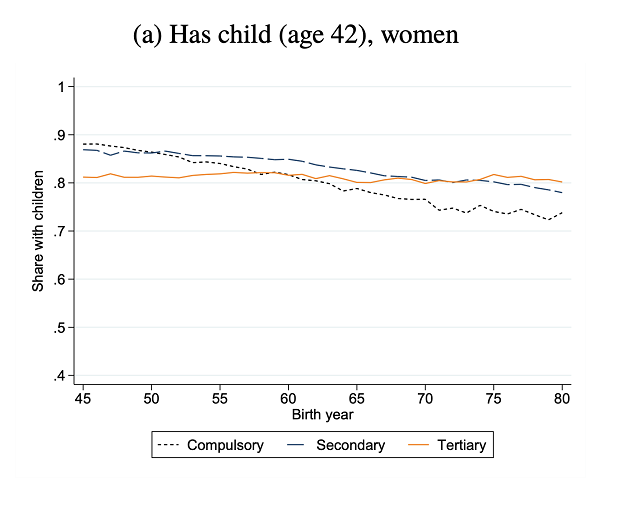

To American readers not versed in international fertility statistics, the simple trends in the following chart—breaking down whether women had kids according to their education and birth year—might be the most striking finding in the whole study. (For reference, “secondary” education lasts three years in Finland, and “tertiary” education goes beyond that.)

Source: Hanna Virtanen et al., “Education, Gender, and Family Formation,” IZA DP No. 17122, July 2024.

Finns have been getting more education over time, so the trends are hard to interpret individually.1 What’s important is that the very direction of the relationship between women’s education and parenthood changed. The most educated women were once the least likely to have kids; now, they’re the most likely. Better-educated Finnish men, meanwhile, have always been more likely to sire children.

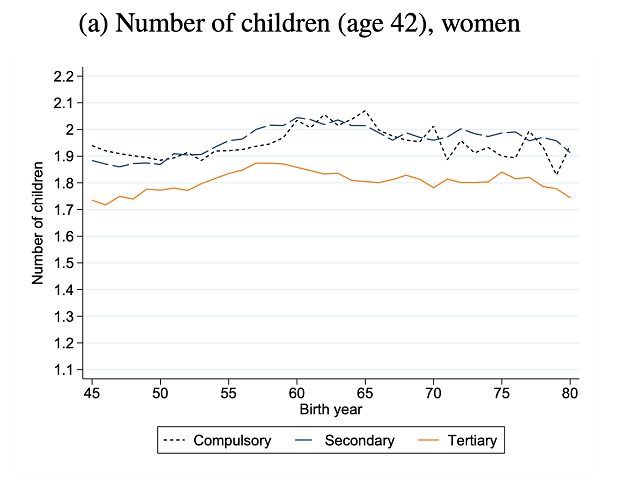

But there’s a catch: Looking at overall fertility instead of the yes/no question of whether a woman had any kids at all, Finnish women with tertiary education are still significantly less fecund than their less-educated peers—though even in that case, those who stop after compulsory education have fallen slightly behind the secondary-education group. The most educated women are the most likely to become parents, but once they do, they still don’t have as many kids in total.

Source: Hanna Virtanen et al., “Education, Gender, and Family Formation,” IZA DP No. 17122, July 2024.

The more educated are also more likely to be married or living with a partner, though this is a bit less surprising. In America as well, marriage has disintegrated primarily among the less educated.

Correlation and Causation

What’s going on here? Are these just broad trends among social groups in a faraway country, or has Finland found a way to make college cause women to become parents, perhaps through its famously progressive gender norms and generous family policies? If the latter is true, it could hold some answers for those wanting to boost fertility in advanced economies throughout the world—though, once again, we should not lose sight of the difference between parenthood and total fertility.

That brings us to the authors’ main analysis. Since Finland keeps extremely detailed “register” data on its citizens, and since it uses simple test-score cutoffs for school eligibility, the authors can measure the effect of going to college at the margins for the most recent cohorts. In other words, do women who just barely make the cutoff become parents more frequently than the ones who just barely miss it?

The results do suggest that admission to tertiary education boosts the chance a woman will become a mother—by 6 percentage points—but the effect of secondary education is statistically insignificant. The effects on the number of children for both women and men, the effects of living with a partner on both women and men, as well as the effects on parenthood for men, are all statistically insignificant. In general, these results feel a little unsatisfying.

To round out their analysis, the authors conducted a survey, finding that:

more recent cohorts of adults in Finland perceive the growing importance of social rather than academic skills in the labor market, and believe that, compared to academic skills, social skills are best developed by parental inputs – and particularly those of mothers. Moreover, we find that younger cohorts of men are increasingly likely to indicate a preference for college educated partners.

Ultimately, I remain skeptical that higher education can actively promote fertility, especially total fertility. It’s interesting, though, that parenthood patterns have flipped for the Finns—say that 10 times fast—and that education at least doesn’t seem to reduce parenthood there.

Does—and Can—This Translate to America?

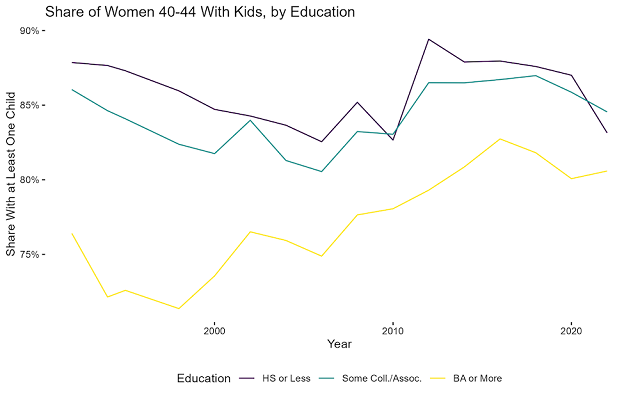

American readers may wonder if similar trends are evident here, so I took a look at the Census’s Current Population Survey, in particular at the total number of births reported by women ages 40-44 since 1992 (i.e., those born from about the 1950s through the early 1980s). I divided education levels into high school or less, some college, and a BA or more.2

One interesting fact (as others have noted as well) is that higher-educated women are less likely to remain childless than they used to be—though the same point about selection applies here as in Finland. (The BA-or-more share rises from about a quarter to about half of the sample from the left of this chart to the right.) But at any rate, there’s little hint of an imminent crossover where the highest-educated women will consistently be the most likely to become mothers.

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey, accessed via: Sarah Flood, Miriam King,

Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper,

Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 11.0 [dataset].

Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2023.

Also worth noting is that since overall U.S. fertility began falling in the late 2000s—and was actually at a relatively high point before the Great Recession—the drop doesn’t show up among women in their 40s until recently. It will be interesting to see what the chart looks like in another decade.

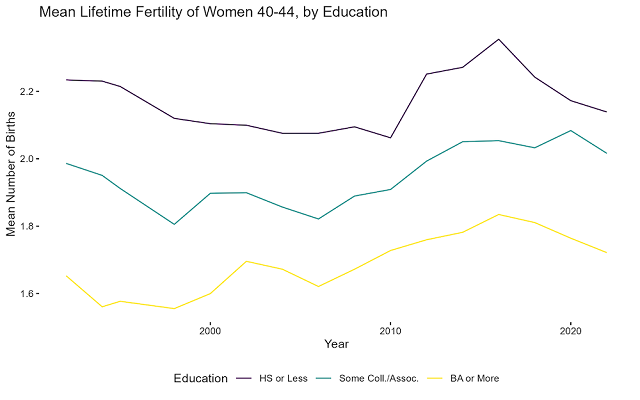

The U.S. data also show a marked difference when one switches from childlessness to total fertility as the outcome of interest. In this case, the “more education, fewer kids” rule never comes close to breaking.

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey, accessed via: Sarah Flood, Miriam King,

Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper,

Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 11.0 [dataset].

Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2023.

Another pattern worth pointing out is that, while higher-educated people make more money on average, patterns for education do not necessarily track patterns for income. In a recent article for IFS, Rosemary L. Hopcroft documented that in many countries, higher earners—especially higher-earning men—are starting to pull ahead in terms of fertility. She also pointed out that if one breaks educational categories down into finer detail, American women with more than a BA have slightly higher fertility than those with just a BA.

There may be some lessons for the U.S. from Finland when it comes to making women’s education and employment more compatible with family life. But we are very different countries, starting from very different places—and sending more people to college hardly seems like a full solution to the First World’s fertility woes.

Robert VerBruggen is an IFS research fellow and a fellow at the Manhattan Institute.