Highlights

- There is a new emerging trend where better-off men and women are more likely to have children than less well-off men and women. Post This

- The rewards of children and family are becoming confined to the better-off, and this trend is likely going to continue. Post This

- In Sweden, it is higher-income, better-educated men and women who are more likely to have children, while lower-income, less-educated men and women are least likely to have children. Post This

The rich countries of the world are not reproducing themselves. A total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.1 (the number of children the average woman will have in her lifetime) is considered replacement fertility. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the TFR in the United States in 2022 was about 1.67. According to the World Fact Book in 2023, the TFR in Sweden was 1.67, in Germany 1.58, and in Japan 1.39. This means that without immigration, the rich countries of the world will soon shrink in size. Falling fertility rates in the rich world, fewer babies, and disproportionately more elderly get a lot of headline space, as they have many adverse societal consequences. These include problems with the government funding of pensions and medical care, as well as increasing loneliness, as a larger proportion of people live by themselves.

Yet the trend at the aggregate level of the whole country disguises trends that are emerging among individuals in these countries. In my new book, coauthored with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber, Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship between Status and Fertility, we document that while in much of the twentieth century it was poor people in countries such as the United States who had more children than richer people, there is a new emerging trend where better-off men and women are more likely to have children than less well-off men and women.

Readers of this blog will not be surprised at this change, given that marriage in the U.S. and other countries is becoming more concentrated among those who are better off financially, and in most countries (even Scandinavia), marriage remains the preferred arrangement for raising children. In an era of an ever-smaller proportion of the population marrying and having children, a stable family life is increasingly becoming the preserve of the affluent elite.

In our book, we present research from a variety of countries in East Asia, Europe, the U.S., and the U.K. documenting the changing relationship between status and fertility. For example, in Japan, high income men are more likely to both marry and have children. Naohiro Ogawa and colleagues found that in Tokyo in 2003, 85% of 25- to 34- year- old men in the lowest income category were unmarried, while only 35%, respectively, of men in the highest income category remained unmarried. In East Asia, childbearing is very tightly connected to marriage, so these higher income men who marry are also more likely to have children. For example, a recent study in PLOS ONE found a positive relationship between annual income and number of children for Japanese men from all birth cohorts from 1943 to 1975, such that higher income men had more children than lower income men, on average. This same trend is also clear in Taiwan, South Korea, and China.

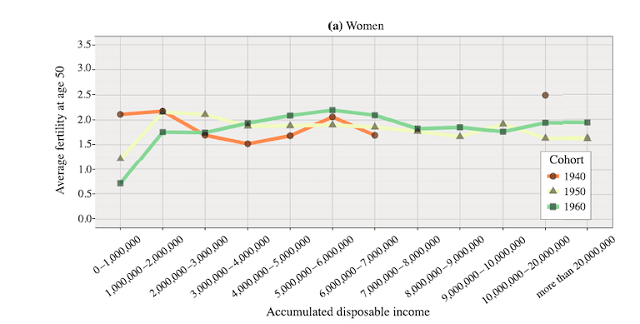

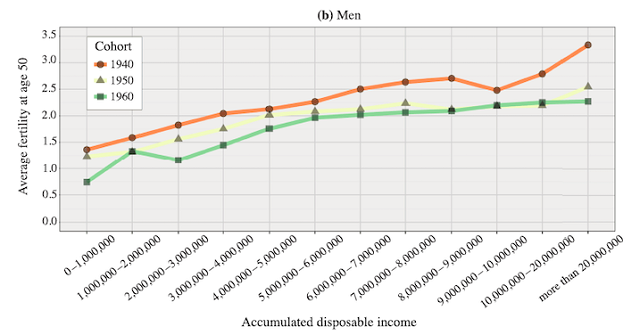

In Sweden, among recent cohorts, it is higher-income, better-educated men and women who are more likely to have children, while lower-income, less-educated men and women are least likely to have children (see Figures 1 and 2). Despite very high rates of cohabitation in Sweden, better-off people with children are also more likely to (eventually) marry.

Figure 1. Average female fertility at age 50 by accumulated disposable income,

for the 1940, 1950, and 1960 birth cohorts in Sweden (Source Kolk 2022)

Figure 2. Average male fertility at age 50 by accumulated disposable income,

for the 1940, 1950, and 1960 birth cohorts in Sweden (Source Kolk 2022)

In the U.S. and the U.K., there is also a positive relationship between personal income (but not education) and the number of children for men, such that higher income men have more children, on average. In the U.S. and the U.K., where there is more fertility outside of marriage but most children are born to married parents, much of the higher fertility of higher income men is because these men are more likely to marry. For example, in a 2022 study published in Evolution and Human Behavior, Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber found a positive association between male income and ever being married in U.S. data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. They found that personal income predicted about a fifth of the variance of ever being married. Income has become more important for men in getting married in the United States. In another study of U.S. Census data, Fieder and Huber found that the variance in ever being married explained by income in men aged 46–55 years increased from 2.5% for men born 1890-1910 to around 20% for men born in 1973.

Figure 3. Predicted number of biological children by total monthly

personal income from all sources for men and women, U.S. (Source: Hopcroft 2023)

For women in the U.S., there is an emerging U-shaped relationship between education and fertility. However, as in many countries, there is still a negative relationship between personal income and fertility for women, such that high income women tend to have fewer children than low income women.

Figure 4. Fertility by women’s education, 1980 and 2010 (Source: Federal Reserve Bank)

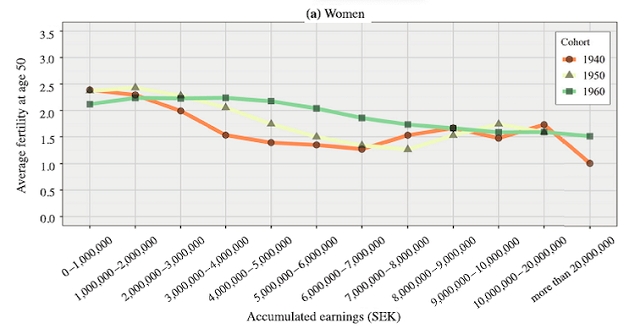

Most of the negative relationship between personal income and fertility for women in the U.S. likely represents tradeoffs women face between earning income and bearing and raising children. This is borne out by data from Sweden where these tradeoffs are ameliorated by generous state benefits for parents: both parents each receive about 8 months in paid parental leave while being paid 80% of their salary. While including such benefits in total income means there is a positive relationship between income and fertility for both men and women, when earnings from work are examined, excluding all of benefits and transfers from the state, high earning women still have fewer children than lower earning women.

Figure 5. Average female fertility at age 50 by accumulated earnings,

for the 1940, 1950, and 1960 birth cohorts in Sweden (Source Kolk 2022)

This negative relationship between earnings from work and number of children for women is because childless women are more likely to work outside of the home all their lives. For example, using data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Renske Verweij and coauthors found that women who worked outside of the home all their lives were about three times more likely to be childless than women who did not work much outside of the home.

The recent change suggests that the rewards of children and family are becoming confined to the better-off, and this trend is likely going to continue. This is not good for individuals, nor is it good for societies as a whole. Yet existing government policies do little to solve the problem. In fact, the governments that do the most for families with two working parents, such as the Nordic countries, are actually at the forefront of this trend.

Our book does not draw policy implications from the change in the relationship between status and fertility, but it is straightforward to do so. Unlike Bloomberg writer Justin Fox—who suggests the solution is to copy the work-family policies of countries like Sweden—I believe this will simply exacerbate the trend toward the rich having more babies.

A better approach is to accept that there are differences between men and women with regards to social behaviors such as sex and parenting (as predicted by theory from evolutionary biology). Work-family policies such as those in the Nordic countries largely ignore these differences and are aimed at facilitating full-time female employment. In part, this is a reaction to a history of patriarchal rules that limit the rights and opportunities of women. Yet there is a difference between eliminating barriers to female participation in the workforce and incentivizing equal employment outcomes for men and women. While laws and policies that limit opportunities for women are unwarranted, stipulating that all workplaces must have the same proportion of men and women, or incentivizing or otherwise encouraging men and women to act in exactly the same way, will likely have negative consequences. Because of sex differences regarding parenting in particular, these policies are likely to inhibit family formation and childbearing. For example, to the extent that such laws or policies mean that women replace men in well-paid jobs, one effect will be that more men end up in jobs that cannot support a family. Even in the Nordic countries, these low paid men are less attractive as fathers, despite the many benefits given to working parents. This means less childbearing among poorer couples.

On the other hand, policies and practices that aid families—such as the provision of better public schools, crime prevention, and the creation of safe neighborhoods, as well as policies that work to limit the costs of healthcare and higher education and encourage the production of family homes—can all reduce the costs of family formation. A pro-family culture is also helpful. While it may be that the rich will always be able to afford more children, social engineering that seeks to eradicate sex differences in work behavior, and policies that increase the costs of schooling, healthcare, and family housing, will only exacerbate this trend.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018), and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).