Highlights

- There’s nothing about modern society that makes “dysgenic fertility” inevitable. Post This

- The supposed “dysgenic” link between cognitive ability and fertility was a flash in the pan. It applied to people of a few particular birth cohorts, but isn’t generally applicable. Post This

- The important thing to understand about “dysgenic fertility” today is that there’s no reason to believe it poses a long-run social problem. Post This

In three prior posts, I’ve written about the relationship between income and fertility. Contrary to popular assumption, there is no persistent link between the two, and no reason to believe that fertility falls as an inevitable consequence of economic growth. Large differences in fertility across societies are mostly due to large cultural differences that are loosely correlated with—but not identical to—economic development, not some inevitable change that happens when GDP per capita goes up. In the 21st century, fertility is beginning to become (as it was before modernity) positively correlated with income.

But one of the reasons the supposedly persistent negative link between income and fertility draws so much attention is the belief that it may be evidence of “dysgenic fertility.” If you’ve ever seen the movie Idiocracy, you know the basic idea: if more educated people don’t have kids, while less educated people do, couldn’t that, over time, lead to a generalized reduction in societal intelligence? This fear of “dysgenics” is the subject of enormous scholarly debate. One reason for this is because of the close link between dysgenic fears and eugenic policies. Fears about reproduction among people perceived as inherently less worthy than others have motivated campaigns of forced sterilization in many countries around the world in the 20th century, including here in America. Indeed, family demography as a scientific discipline was essentially invented as a tool to study “differential fertility,” that is, differences in fertility rates across different social classes or groups. For many years from the 1920s until the 1940s, the most prominent academic journals in fertility studies were the overtly-eugenicist Milbank Quarterly or Eugenics Quarterly. Fears that modern pronatalism may also be rooted in eugenics are common, and were recently highlighted in an online symposia of demographers opposed to pronatalism.

My goal here is not to debate whether dysgenic fears or eugenic goals influence modern pronatalism. Rather, my goal is to raise a simple question: Is there any empirical basis to worry that Idiocracy will come to pass? Is it really true that higher birth rates by less educated people will lead to a great dumbing-down of society? As offensive as the notion can be, simply labeling it too taboo to discuss won’t persuade anybody. But as I’ll show below, “dysgenic fertility” simply is not a serious threat to society.

How Genetic Is Intelligence?

Scholars have spilled a virtually limitless stream of ink on the question of what intelligence is, how to measure it, and whether it has any genetic component. I won’t waste time rehashing that debate here. For the purposes of this article, we will take what seems to be a reasonable middle-of-the road position. Across 50 years of research on intelligence across kinship ties that involved hundreds of studies, it appears that about 50% of human variation in cognitive traits can be explained through biological kinship. Modern genetic studies have identified numerous genes thought to influence cognitive ability, but they suggest a considerably lower degree of heritability: 20-40%. The exact numbers don’t matter here; what matters is that for this article, I’ll work with the assumption that cognitive abilities are a real, meaningful construct that have at least some genetic component. Unfortunately, the usual way geneticists measure cognitive ability indicators in genes actually is not based on genes predicting intelligence, but based on genes predicting educational attainment, which is not, strictly speaking, the same thing. Genes related to educational attainment probably are less predictive of actual intelligence than genes known to be related to intelligence.

Are Genes Related to Educational Success Getting Rarer?

The first place to look to see if dysgenic fertility could be an issue is large population genetic registers. In these big datasets of human genetic data, researchers can ask: are genes believed to predict intelligence more common or less common in more recently-born cohorts (younger people) than earlier-born cohorts (older people)? Taken at face value, these studies suggest that the genes associated with higher intelligence seem to be getting less common over time in some countries. Of five studies I could find, studies in Iceland, the U.S.,and the U.K. suggest declines ranging from 0.3 to 0.9 IQ points per generation, while studies of Estonia and Finland suggest no decline and maybe even a slight increase.

On its face, 3 countries out of the 5 identified here with declines of 0.3-0.9 IQ points per generation seems like a pretty big point in favor of “dysgenic fertility” being real. But the devil is in the details.

First of all, virtually the whole U.S. decline occurred among cohorts born before 1950 with very little decline in more recent cohorts. In other words, genes related to intelligence predicted lower fertility among the Greatest Generation and early Boomers, but not among late Boomers and Generation X. The U.K.’s implied decline is extremely small, much more modest than the U.S. decline. Iceland’s decline is fairly significant and persistent, but Iceland is also a bizarre case, since Icelanders are very few in number and have astronomically higher odds of being actually related to people they might meet in everyday life. Whether a society with what geneticists call high “background relatedness” generalizes to extremely diverse societies like the United States is far from clear. And of course Estonia even saw a modest increase in genes associated with higher educational attainment.

These details tell us something important: there’s nothing about modern society that makes “dysgenic fertility” inevitable. The extent of any “dysgenic fertility” varies across time and space such that there is no universal rule of dysgenesis across otherwise similar societies. And in fact, even direction of change varies across industrialized countries. It may be the case that there are periods of a few generations when there is a more negative or positive gradient between genes related to cognitive ability and fertility, but evidently these kinds of correlations are not highly durable over time. Just because genes related to cognitive ability got slightly less common across a mere two or three generations in some of the countries where we have data doesn’t mean we should jump to the assumption that, inevitably, fertility will always and everywhere in the industrialized world tend towards “dysgenic” effects.

Are Genes Related to Cognitive Ability Linked to Fertility?

It's not at all surprising that trends in genes related to cognitive ability would vary so much across time and place, since studies of the genetic roots of fertility have shown that which genes predict high fertility varies widely across modern societies. To put it another way, humans around the industrialized world aren’t converging towards genetic similarity. A gene that predicts having more babies in one country may actually predict having fewer in another! The best genetic study of fertility even found that most genes related to fertility have different effects for men and women. It’s extremely easy to imagine how this could happen. Some genes cause people to be taller. Height might be an advantage on the dating market for men, but less of an advantage for women—at least in America. But maybe in another country (say, France), genes related to height might be more of an advantage for women! In other words, fertility can’t be genetically converging towards lower intelligence around the industrialized world since we already know fertility is barely genetically converging towards anything at all. It’s hard for fertility to be persistently “dysgenic” if, in fact, there aren’t even many genes that persistently predict fertility across industrialized societies.

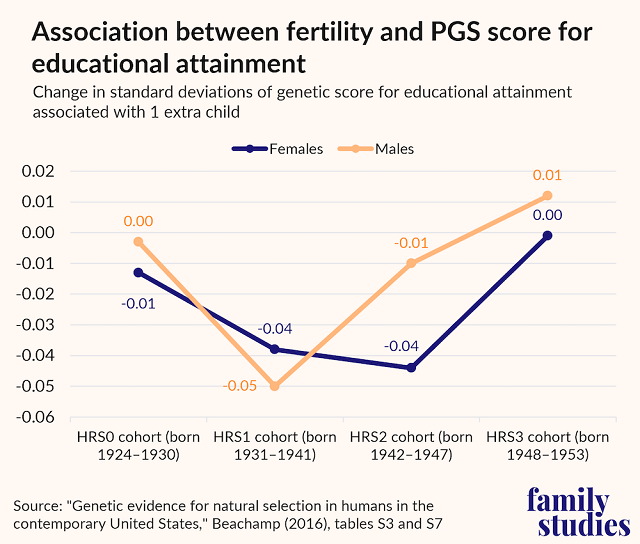

More than that, one recent study estimates how genes for educational attainment have related to fertility across different generations, and finds that there is no dysgenic fertility in the youngest cohort (in this case, the “youngest cohort” is people in their 70s today):

The finding here is obvious. For American men and women born 1931-1947, there was probably a real negative link between the genes that predict education (largely genes related to cognitive ability) and fertility behavior.

But that wasn’t true for the 1924-1930 birth cohort, nor for the 1948-1953 birth cohort. The point is: the supposed “dysgenic” link between cognitive ability and fertility was a flash in the pan. It applied to people of a few particular birth cohorts, but isn’t generally applicable. Maybe dysgenic trends will appear again among parent generations born in the 1960s, or 1970s, or 1990s—or maybe they won’t! The point is, these correlations between genes related to cognition and fertility outcomes appear and disappear at various times and likely drive little or no long-run change in society-wide cognitive ability.

Finally, those studies showing declining genetic scores for intelligence are probably just wrong for a very simple reason. The genes that predict higher cognitive abilities also predict longer lifespans. We also know that the genes that predict higher fertility predict shorter lifespans. The studies I linked to earlier used genetic data collected since the year 2000, and estimate polygenic scores for past generations by taking genetic data from surviving old people.

But if genes for education make you live longer, and if genes for fertility make you die younger, then old people will disproportionately have higher education genes and lower fertility genes. This, in turn, means the genetic data will be massively biased over time: it will almost always look like younger generations are genetically selected for “high fertility, low intelligence” genes compared to older generations, because survival to old age itself is predicted by “low fertility, high intelligence” genes.

Unless and until we have large, population-representative samples of young people showing declining prevalence of cognitive-ability-related genes, there’s just nothing to the entire “dysgenic fertility” argument. Finally, it’s worth noting that pooling all 20th-century genetic results together, one recent study does show that 20th-century people of European descent have much higher rates of genes related to intelligence than Europeans did 500 years ago, so at least on that timespan, the real trend is not “dysgenic” but “eugenic”: people with genes predicting greater cognitive ability evidently had more babies than other people over the space of half a millennia.

“Dysgenic fertility” is a hotly debated topic for many reasons, not least its historic association with policies of eugenic sterilization and racist ideologies. But the important thing to understand about “dysgenic fertility” today is that there’s no reason to believe it poses a long-run social problem. In some generations, cognition predicts having slightly more children; in others, it predicts having slightly fewer children. In the long run of human history, the trend in cognition-related genes is up, not down, and the income-fertility data (to the extent income is correlated with cognitive ability) suggests that, if anything, this long-term trend is likely to continue unbroken.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.