Highlights

- The gap between the fertility of more- and less-educated women has been converging for several decades. Post This

- Earnings have different effects on men and women’s completed fertility: positive for men, negative for women. Post This

- Across both cohorts of women and all three racial groups, there’s a clear tradeoff between women’s earnings and their family size. Post This

In a prior post, I discussed how income-fertility correlations are biased due to “cultural stratification,” meaning that people with different incomes often have different cultural norms and backgrounds, and so their fertility differences aren’t really caused by income. My conclusion was simple: once we control for cultural background, income and fertility do not have a consistent connection to each other and, in many cases, are positively correlated. This should nudge us towards believing that global fertility declines are not completely driven by global income increases.

In this post, I’ll cover another problem: young people tend to have rather low incomes, while older people tend to have high incomes, but young people have an easier time conceiving children. As a result, both income and fertility have unavoidable, inherent relationships with age. Because young people tend to be poorer, modeling fertility on income as I did in the prior section in some sense is just measuring the fact that non-Hispanic white women, for example, have children later in life, when they are wealthier, while black women have children earlier in life, when they are poorer.

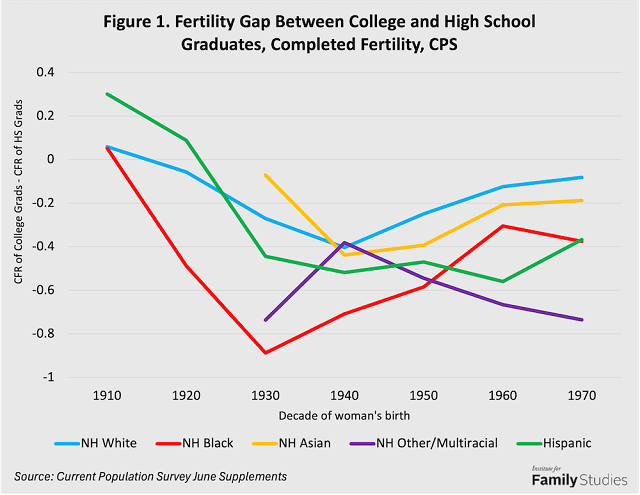

There are several ways to deal with this. The first is to leverage the fact that people with more education tend to be richer. By looking at completed fertility of women with varying levels of education, it’s possible to eliminate any bias due to timing. The figure below shows the gap in final family size between women with college degrees and women with just a high school degree, across multiple decades and ethnic or racial groups.

For women born in the 1910s and 1920s, education has little predictive value for fertility, except among black women. For Hispanic and white women, there is not much difference between college graduates and high school graduates.

But for women born in the 1930s and 1940s, there is a very large gap. For every racial-ethnic group born in the 1940s, college women have at least 0.4 children fewer than non-college women, a very large difference, and for black women the effect is around 0.6-0.9 fewer children. So it looks like the classic story of higher-income people having fewer kids.

On the other hand, for more recent cohorts of women born in the 1960s and 1970s, this negative effect of education has eroded. Today, there is almost no difference between college-graduates and non-college graduates among non-Hispanic white women, and very little difference among Asians. Differences have proved more durable among Hispanic and black women. This pattern is very similar to the one observed in the prior post: culture matters for fertility. For whatever reason, for women born in the mid-20th century, the cultural norms to which less- and more-educated women were exposed had a lot of variation. But for more recent cohorts, especially for white and Asian women, it seems like there is not as much difference. The negative effect of higher income and status is not only inconsistent across cultural background, but it is also inconsistent over time. Any negative relationship between income and fertility is not an immutable fact.

Lifetime Earnings and Fertility, by Race and Sex

Another way to tackle the age-income-fertility relationship is to use longitudinal surveys to measure how income shapes fertility. For this, I use the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 cohort (NLSY79) and the NLSY 1997 cohort (NLSY97).1 Using this data, it’s possible to calculate lifetime personal earnings, lifetime family income, and lifetime spousal earnings for about 6,000 men and women born 1957-1962, and also to see how their ultimate fertility outcomes varied, since today these men and women are in their 50s and 60s.2

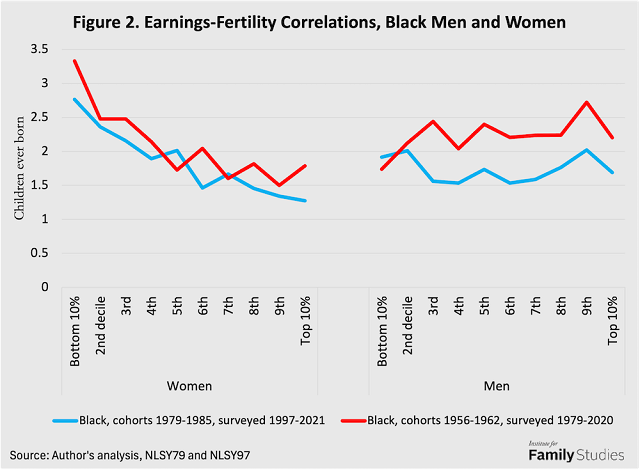

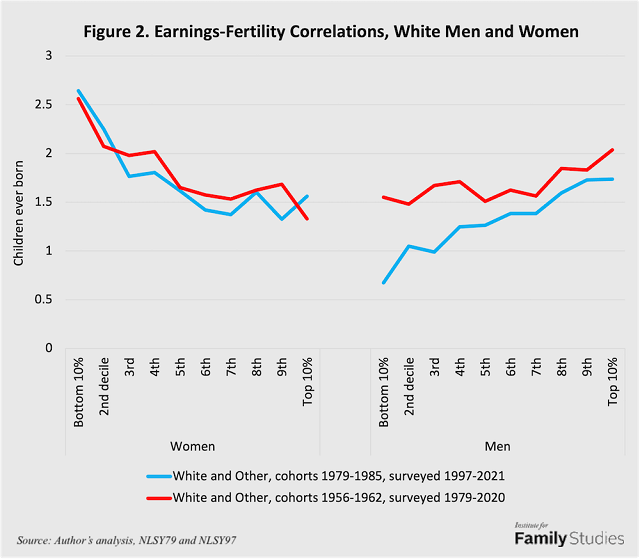

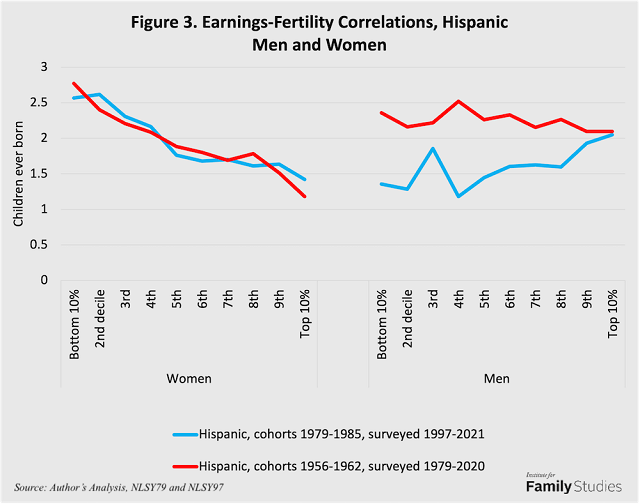

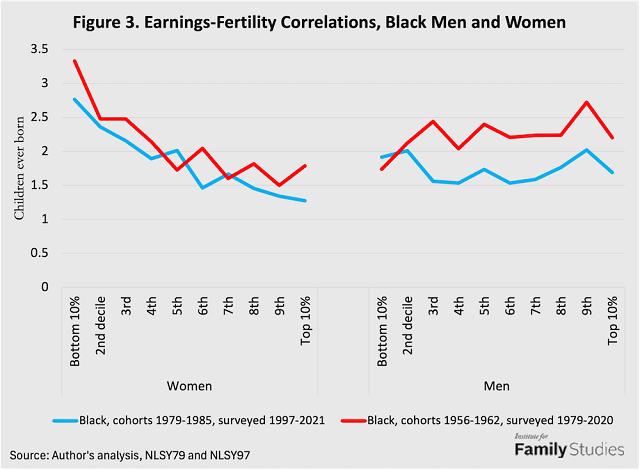

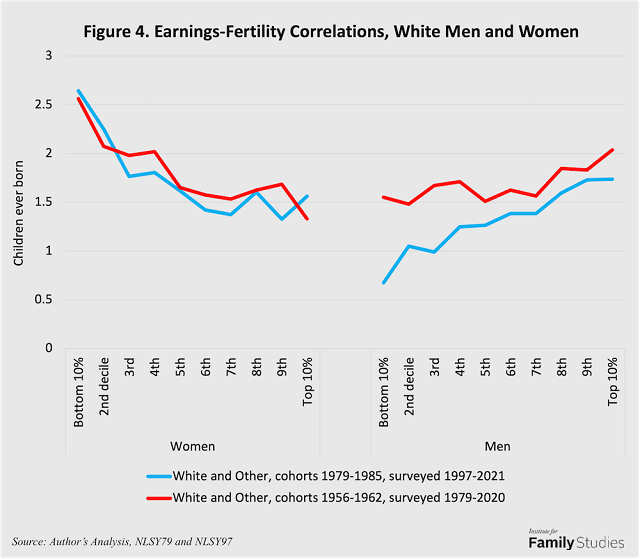

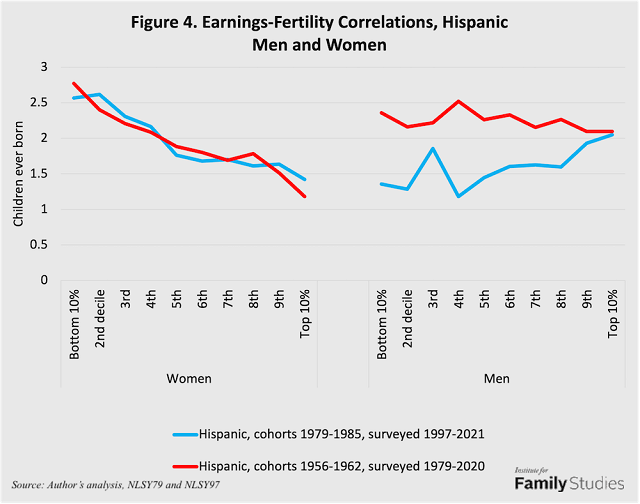

The figures below show correlations between respondent earnings and fertility, by racial/ethnic background, sex, and survey cohort.3

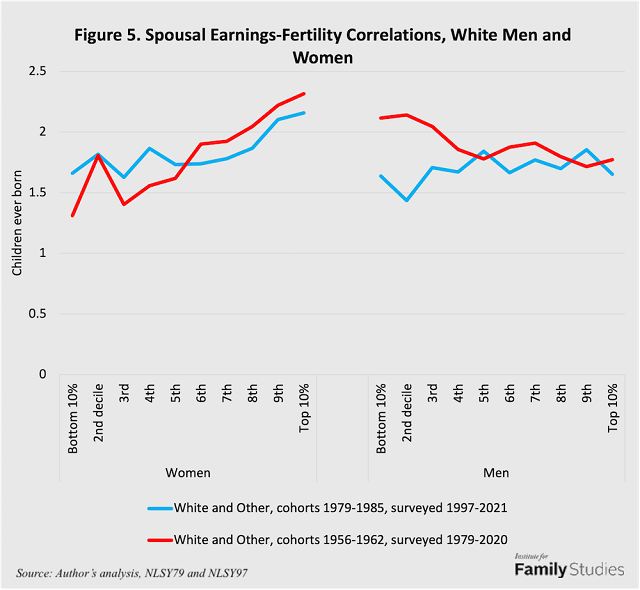

Let’s start with earnings, which is what most people often think of when discussing income, but really isn’t the same thing. Earnings in this case includes any income derived from wages, salary, farming, or self-employment for the individual. So, a woman wouldn’t count her husband’s earnings here, nor a husband his wife’s; and neither would count welfare benefits or investment income. We’ll start with data for non-Hispanic white men and women since they are the largest group in these samples.

For whites, it is the case in both cohorts that fertility falls as women earn more, though most of this effect is as earnings fall from the bottom to the 5th decile. There’s no decline in fertility as women’s earnings rise from the median level to high earning. Thus, the big fertility decline for white women is not in the shift from “school teacher or nurse” to “corporate lawyer or doctor,” but in the shift from “nonworking or temporary work” to “school teacher or nurse.” Women who are “girl bossing” (i.e., have very high lifetime earnings) have about the same fertility as women with shorter or less lucrative working careers, though both have lower fertility than women with very short or very low-paying working careers.

For whites, it is the case in both cohorts that fertility falls as women earn more, though most of this effect is as earnings fall from the bottom to the 5th decile. There’s no decline in fertility as women’s earnings rise from the median level to high earning. Thus, the big fertility decline for white women is not in the shift from “school teacher or nurse” to “corporate lawyer or doctor,” but in the shift from “nonworking or temporary work” to “school teacher or nurse.” Women who are “girl bossing” (i.e., have very high lifetime earnings) have about the same fertility as women with shorter or less lucrative working careers, though both have lower fertility than women with very short or very low-paying working careers.

For white men born 1956-1962, the correlation between earnings and fertility is rather modest: a 0.5 child difference between the lowest-earning and highest-earning men, though note that the relationship is positive. But for white men born 1979-1985, the correlation is quite dramatic: the richest men have 0.7 to 1 children more than the poorest. In fact, high earning men in the more recent birth cohort have twice as many children as low-earning men!

So, this tells us a few things: first, the effect of earnings on fertility may not be stable over time. It was for white women, but not for white men. Second, earnings have different effects on men and women’s completed fertility: positive for men, negative for women.

Turning next to black respondents, there’s clear evidence of cultural stratification in comparison to whites. Black women have lower fertility across almost all income ranges, but in general the negative correlation between black women’s earnings and their fertility was stable. But for black men, the association between earnings and fertility has changed, and in the opposite way observed for white men: the highest-earning black men now have basically the same fertility as the lowest-earning black men, even though in the 1956-1962 birth cohort, higher-earning black men had more children.

So, it’s not just that the earnings-fertility association can change over time, nor that there may be cultural differences in earnings-fertility relationships; it is also that different cultural groups might experience totally different changes over time in how earnings relate to fertility. This further strengthens the notion that there is no intrinsic connection between economic well-being and low fertility.

So, it’s not just that the earnings-fertility association can change over time, nor that there may be cultural differences in earnings-fertility relationships; it is also that different cultural groups might experience totally different changes over time in how earnings relate to fertility. This further strengthens the notion that there is no intrinsic connection between economic well-being and low fertility.

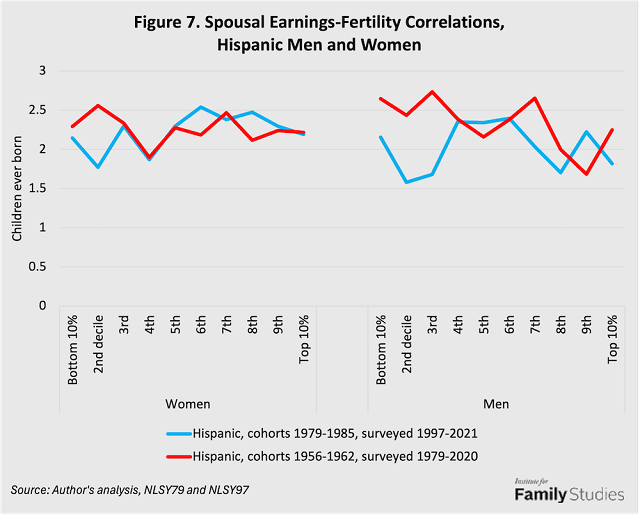

For Hispanic women, again, the negative correlation between earnings and fertility is very clear and stable across both cohorts (no change). But for Hispanic men, there’s been a huge change. In the NLSY79 cohort (men born 1956-1962), there is basically no link between male earnings and male fertility. But for the NLSY97 cohort (men born 1979-1985), there is a very clear link: higher-earning Hispanic men have far more children than lower-earning Hispanic men. Hispanic men became more similar to white men in this regard.

For women, the negative association between their own earnings and fertility is pretty stable. But the link between men’s earnings and fertility changes in every group, and in different ways. This tells us that men’s earnings do not have an inherent connection to fertility.

For women, the negative association between their own earnings and fertility is pretty stable. But the link between men’s earnings and fertility changes in every group, and in different ways. This tells us that men’s earnings do not have an inherent connection to fertility.

Lifetime Spousal Earnings and Fertility

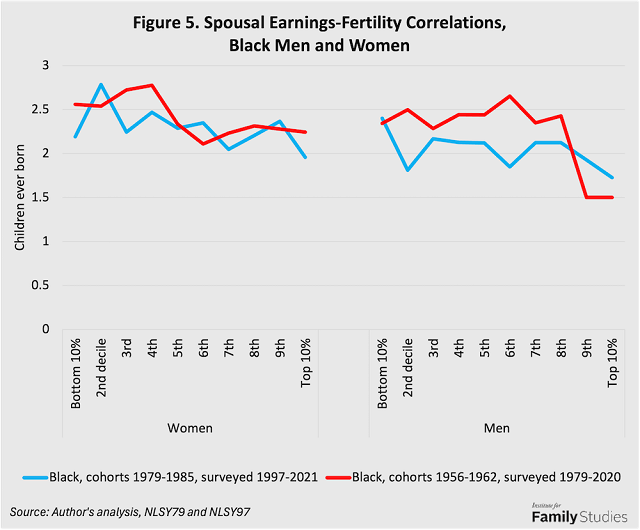

Next, we can look at spousal earnings across cohorts. For this variable, I take each respondent’s reports of their spouse’s earnings in each year and sum them up. Individuals can have higher spousal earnings because they were married for more years, or because their spouse spent more years employed, or because their spouse had higher earnings while employed.

In both periods, for white women, higher-earning spouses are clearly associated with higher fertility for women, though the effect has weakened a bit. However, for men, the effects change. In the 1956-62 birth cohort, men with low-earning spouses had the most children. This is consistent with the idea that for men born 1956-1962, their fertility was highest if they had a stay-at-home wife. But in the 1979-85 birth cohort, men with low-earning spouses have the fewest children: men with low-earning or stay-at-home spouses turned out not to have that many children, a striking shift.

For black women, there was basically no effect of spousal earnings on fertility in either cohort. That is, black women whose spouses earn more money have about the same fertility as black women with very low or no spousal earnings over their life course. For black men, exact effects vary, but in both cohorts, it looks like there’s no obvious link between black men’s fertility and their spouse’s earnings.

For black women, there was basically no effect of spousal earnings on fertility in either cohort. That is, black women whose spouses earn more money have about the same fertility as black women with very low or no spousal earnings over their life course. For black men, exact effects vary, but in both cohorts, it looks like there’s no obvious link between black men’s fertility and their spouse’s earnings.

Turning to Hispanic women, in the 1956-62 birth cohort, there’s no effect of spousal earnings on women’s fertility. But in the 1979-85 birth cohort, it does look like fertility is lower for women with lower-earning spouses. For men, in the 1956-62 birth cohort, having higher-earning wives is perhaps associated with lower fertility; but in the 1979-85 birth cohort, that is no longer true.

Across these comparisons, we can see that spousal earnings often matter as much or more than an individual’s own earnings. For the sake of space, I have limited the graphs to just these six figures, but the effects I’ve described here are similar after controlling for years of marriage and when looking only at spousal employment and overall earnings without penalizing individuals for years without a spouse. Across several groups, we can see that men’s fertility has no penalty if their spouse works in recent cohorts.

Conclusion

There is no straightforward relationship between income and fertility. The gap between the fertility of more- and less-educated women has been converging for several decades. In general, to the extent income is related to fertility, this effect is culturally mediated. In some groups, like non-Hispanic whites, higher male income predicts higher male fertility, and women with more spousal income over their life course also have higher fertility. In other groups, like non-Hispanic blacks, neither male income nor women’s spousal income predicts higher fertility. Thus, “boosting male earnings” is not a universal path to higher fertility.

It's striking that for the NLSY97 cohort, wives’ earnings do not predict lower fertility, but earnings do predict lower fertility for women in general. This strongly suggests that women’s earnings are associated with low fertility mostly by reducing marriage.

[These findings] suggest that time, and not money, is the real reason earned income is negatively related to fertility.

How might higher earnings reduce marriage for women? Well, a recent study shows that women continue to “assortatively mate with” (i.e. prefer as partners) higher-earning men. In fact, women have become more selective with respect to men’s income than in the past! Higher-earning women may have a hard time finding men who earn more than they do, especially as young men’s economic prospects are dimming.

But why is it that higher male earnings do not drive higher fertility for black men and women? Family instability may be the issue here. Black women with high spousal earnings are more likely to have multiple spouses than white women with high spousal earnings (who are more likely to have accrued those earnings via a single high-earning spouse). In communities where marriages are less stable, it may be more difficult for couples to create the kinds of secure commitments that enable mutually beneficial resource sharing. Put bluntly, if newlyweds think divorce is plausible, they may not share money as well, which may push women to forego children and invest more in their careers. Economic research strongly supports the notion that this kind of dynamic can be influential in marriages.

On the other hand, women with higher lifetime personal earnings tend to uniformly have lower fertility. Across both cohorts of women and all three racial groups, there’s a clear tradeoff between women’s earnings and their family size. This tradeoff doesn’t exist for women’s income other than personal earnings (especially spousal income, but I also find similar non-effects for investment income, government supports, rents, royalties, gifts from family, etc.). That there’s no fertility tradeoff for these income sources (and possibly even a positive relationship for some groups) is an important fact, as it shows that income alone doesn’t reduce fertility. Only women’s earned income is negatively related to fertility.

This suggests that time, and not money, is the real reason earned income is negatively related to fertility. Children demand significant time commitments that can be hard to reconcile with the intensive career commitments that yield high lifetime earnings. It is not the case that when women have more income, buying power, and economic empowerment they no longer desire kids; rather, when women’s only path to economic prosperity and empowerment is their own earnings, it becomes difficult to balance the time demands of children and work.

Lyman Stone is senior fellow and director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.

1. These respondents were ages 14 to 22 in 1979 and were surveyed as recently as 2020. In every wave, they were asked about their earnings, all income sources in their family, and their spouse’s earnings.

2. For the NLSY97 cohort, about 5400 men and women born 1979-1985, I observe their fertility and incomes up through ages 36-43. This later cohort isn’t quite done having kids and so results for them may not be quite as reliable, but should give at least a general sense of if the relationship between lifetime income and fertility is similar for across these two generations.

3. For simplicity, I’ve broken up income levels into deciles, so that each point on the line corresponds to the 10% of NLSY respondents within a given cohort who had income, earnings, or spousal income in a certain range.