Highlights

- African fertility is basically where one would expect based on African child mortality rates. Post This

- African fertility is not extremely high when compared to benchmarks that reflect actual material conditions, not just an arbitrary assumption by demographers about how fast fertility should fall. Post This

- Western organizations have no right, and no moral credibility, to step in and tell African women what they should or shouldn’t do with their bodies. Post This

Africa’s population is growing fast: faster than the United Nations expected, and faster than some demographers can adequately explain. This has raised concerns among some commentators, particularly non-African elites, that Africa’s birth rate is too high, even unusually high. President Emmanuel Macron, who is childless, previously said that Africa’s poverty was thanks to its high birth rates, and more recently quipped, at an event for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “Present me the woman who decided, being perfectly educated, to have seven, eight or nine children.”

Of course, many educated women do, in fact, choose to have many children. In response to Macron’s comment, the #PostcardsforMacron hashtag was launched on Twitter to highlight educated moms with many kids. But Macron’s comment was in the spirit of the event, as the Gates Foundation’s own “Goalkeepers Report” recently suggested that “Africa as a whole is projected to nearly double in size by 2050, which means that even if the percentage of poor people on the continent is cut in half, the number of poor people stays the same.”

Indeed, the whole report focused on population as a key driver of Africa’s poverty.

What’s really going on here is quite simple: United Nations demographers have repeatedly messed up their forecasts of African fertility in more-or-less the same direction, and, rather than give a good explanation about why that is, the development community is responding by faulting Africans for having kids.

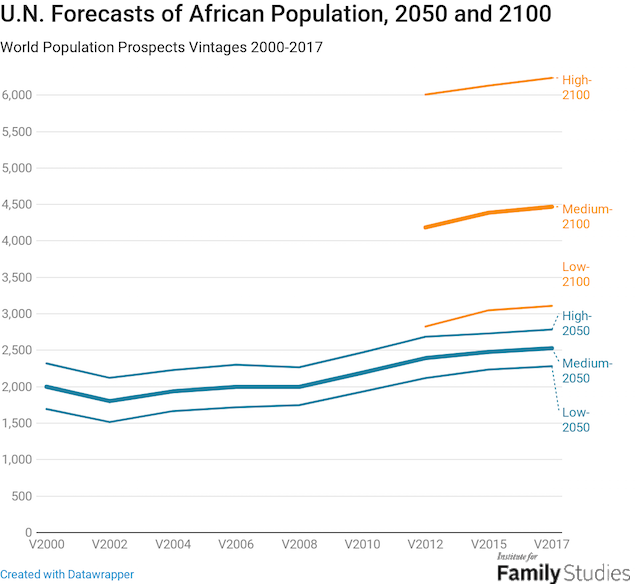

The United Nations’ forecasts for African population by 2050 have been steadily increasing with each new population forecast. Demographers have published papers bemoaning Africa’s curiously slow “demographic transition” to near-replacement fertility. This upward trend in forecast population stems from the fact that U.N. demographers have repeatedly overestimated how quickly Africa’s fertility would decline.

Note that some writers have focused on population estimates in 2100, sharing the 4 billion population forecast: however, 80-year forecast windows are highly unreliable, and the error range provided by the United Nations for 2100 is phenomenally large. Forecasts for 2100 should mostly be ignored.

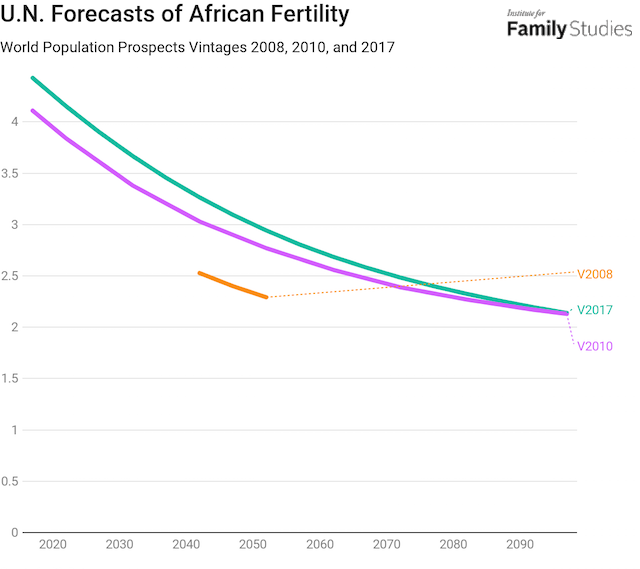

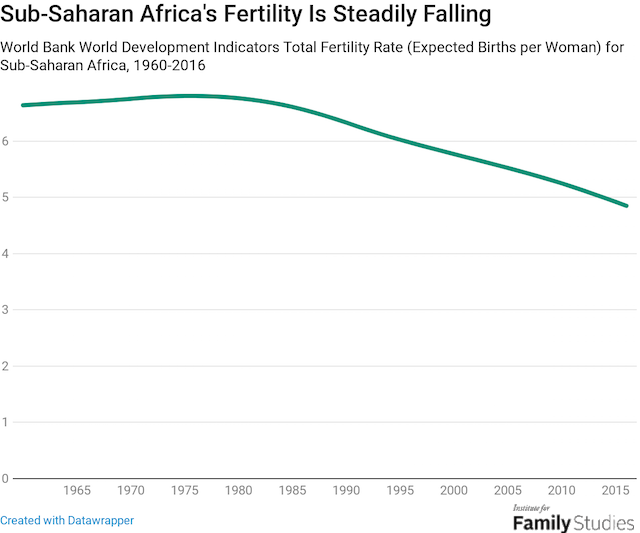

As you can see, forecasts of future fertility rates for Africa have tended to rise over time in official U.N. projections. You might think, then, that Africa’s fertility is rising! But actually, it isn’t! African fertility is falling!

So, if Africa’s fertility is already falling, and if the typical Sub-Saharan African woman already doesn’t fit the stereotype of having about 6 or 7 kids, but rather has 4 or 5 kids, and this average is falling, then what’s the problem? Why does the U.N keep getting it wrong?

The answer turns out to be important: fertility just isn’t falling as fast as the U.N. expects and as some elites in rich countries seem to desire. The entire scary story about African fertility really boils down to fractional differences in the rate of future fertility decline. In other words, Macron’s comments about “6 or 7 or 8” kids are totally irrelevant. Africa’s “problem,” as far as U.N. demographers are concerned, isn’t women having seven kids today; it’s women having three kids, 40 years from now when they “should” have had just two.

Of course, white westerners complaining about African population is a time-honored tradition; that is, it’s part and parcel of old-school racist colonialism. Colonial regimes often tried various inhuman measures to reduce population growth. It’s no surprise the successors to colonial regimes, do-gooder “family planning” NGOs, are pushing the same concerns.

African Fertility is Normal

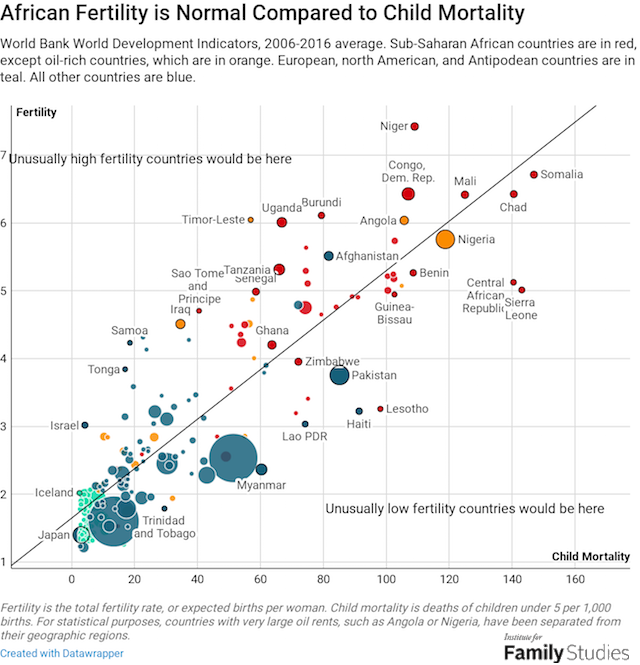

The truth is, however, that the fear-mongering over African fertility is completely misplaced. Africa’s demographic transition isn’t slow at all: it’s right about where a rational forecaster would predict.

The best measure of the general level of economic modernization as far as family and reproduction are concerned is child mortality. In rich countries, it’s rare for children to die. In poor countries, it is distressingly common. Thus, throughout history, a country’s rate of child mortality is one of the best predictors of its fertility rate. Basically, as countries get healthier and richer, families can expect that more kids will survive to adulthood, so they don’t need to have as many children. Plus, people get more educated, and better able to manage their fertility. Finally, the shift away from agriculture towards urbanized economic activities, where brains are often more useful than brawn, reduces the economic advantage of having lots of children. Overall, child mortality is a decent predictor of these trends.

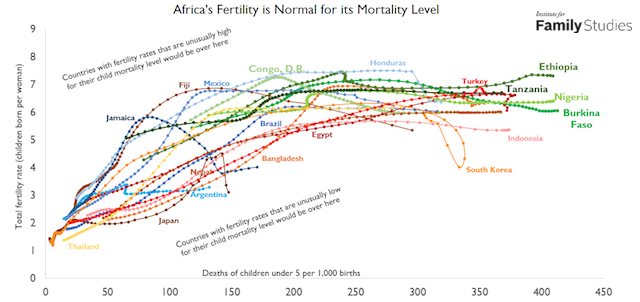

As you can see, African fertility is basically where one would expect based on African child mortality rates. In other words, there is no African fertility paradox or mystery! There’s no need for a special explanation of African birth rates! Adding in control variables for urbanization or dependence on agriculture or natural resources doesn’t change the story: African fertility looks fairly normal for its level of development.

The graph below shows the historical path, from 1935 to 2015, of fertility and child mortality for selected African and other countries, using data from Gapminder. As you can see, African countries, in green, don’t look all that unusual. During periods of civil war and unrest, fertility gets unusually high, but other than those periods, the only one of these countries that may be a serious outlier on fertility today is Tanzania. Ethiopia actually has lower fertility today than South Korea had at a similar level of child mortality.

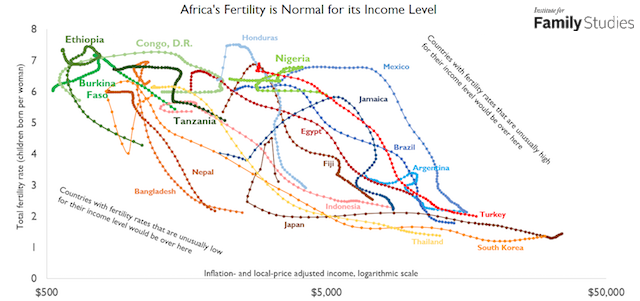

We can produce a similar graph looking at inflation- and local-price-adjusted income instead of child mortality as well. It yields a very similar conclusion: African fertility is not extremely high when compared to benchmarks that reflect actual material conditions, not just an arbitrary assumption by demographers about how fast fertility should fall.

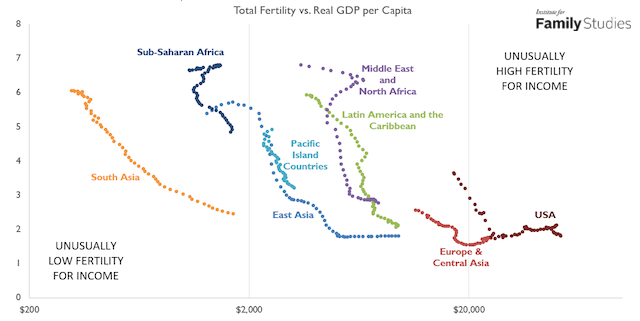

We can also look at bigger aggregates and compare whole regions over time. The graph below uses World Bank data from 1960 to 2016 and shows region-level fertility transition versus income.

As can be seen, Africa’s fertility is quite normal for its income levels. Some regions have had lower fertility, like Asia, and others have had higher, like Latin America or the Middle East. Africa doesn’t look unusual at all and actually has lower fertility at its income level than East Asia had when it was at a similar income level.

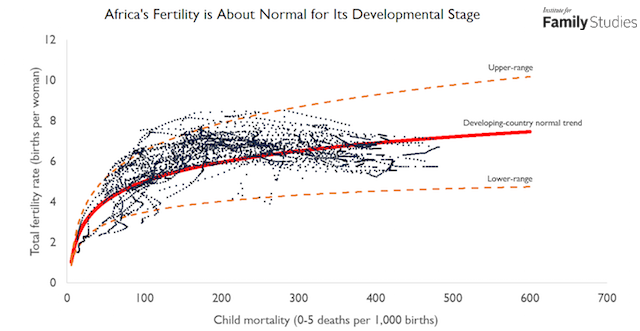

It requires too much data to conveniently present every country like this, but the graph below shows every Sub-Saharan African country’s fertility and mortality from 1935 to 2015, as well as the statistical range of where most countries fall, again using Gapminder data.

As you can see, African countries do look like they have moderately-higher fertility than other countries at a similar stage. However, for the most part, they are well within the normal statistical range, and as African countries reach their most developed levels, with child mortality under 75 deaths per 1,000 births, they seem to rapidly fall to average or below-average fertility. And it turns out, a very large amount of that anomalously high fertility can be explained by countries that were still colonized or were experiencing wars. In other words, the problem wasn’t “Africa” but “Western colonization and its legacy.” It takes time for a country to put itself together after those events, and so it makes sense that African countries would experience a short period of above-average fertility.

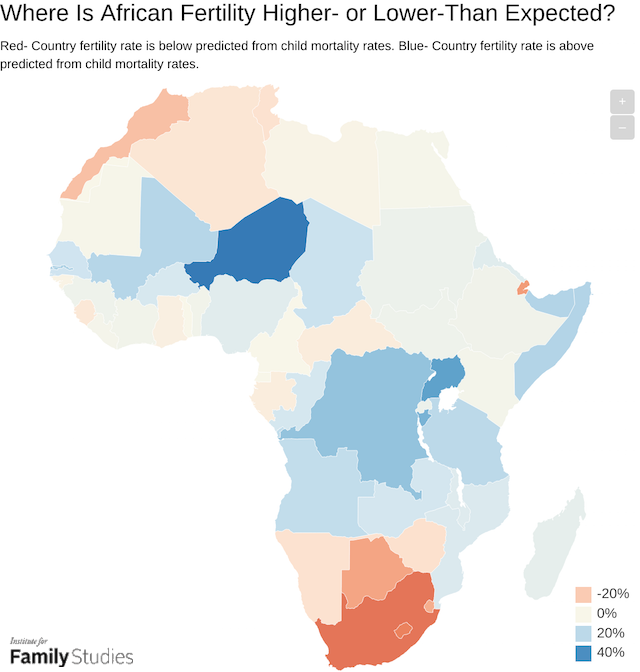

Finally, the map below shows every Sub-Saharan African country today, shaded by whether their fertility is higher or lower than we would expect based on their child mortality, based on a simple model from child mortality and World Bank fertility estimates.

Some parts of Africa have unusually low fertility, like South Africa, Morocco, Botswana, or Djibouti. These countries have experienced accelerated fertility declines relative to the typical global experience. Other countries do seem to have genuinely higher fertility than is typical for their development level, like Niger, Uganda, or Burundi. But most countries are lightly-shaded, indicating that their fertility levels are very near what you’d guess based on their child mortality rates. Even some very poor African countries actually have lower fertility than you’d expect, like the Central African Republic or Sierra Leone.

In other words, not only is African fertility, in general, declining at a rate very similar to what other regions experienced, but the experience within Africa is extremely diverse. When Western elites lump all of these countries together as just “Africa” or “Sub-Saharan Africa,” they end up talking about every country in this huge region as if it were Niger or Congo.

Population Policies Must Respect Individual Liberty

But perhaps more importantly, my sample of “other developing countries” is heavily skewed by the fact that many developing countries have engaged in controversial and often inhumane fertility suppression programs. The most famous is China’s One Child Policy, which reduced China’s fertility at an enormous humanitarian cost. Likewise, in India, fertility has been reduced partly through less-than-voluntary sterilization camps. Comparing African countries to places where governments cruelly robbed people of their right to reproduce and saying African fertility is higher is both no surprise—and no criticism of Africa.

Unless, of course, groups like the Gates Foundation have in mind that Africa should experience China- or India-type fertility declines, in which case their implicit argument is that Africa should implement coercive fertility suppression policies. The Gates Foundation’s report explicitly eschews these policies and calls for only such measures as can empower reproductive choices, but by the Gates Foundation’s own estimates, even if African fertility were reduced to only the children African women wanted, there would still be a doubling of the population, which is precisely the scenario the Gates Foundation fears. In other words, Western donors need to get their story straight: do they want Africa to experience East-Asian style fertility declines, or do they want African countries to pursue democratically-compatible, rights-respecting population policies? You can’t have it both ways.

Of course, it’s not clear why Western donors should get any say in the matter. Colonialism ended, and good riddance! Western countries should have learned their lesson: it’s time to stop acting like African policy can be made from London or Paris or Seattle. Truth be told, Western organizations have no right, and no moral credibility, to step in and tell African women what they should or shouldn’t do with their bodies. We would be much better off looking for ways to solve our own fertility problems.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He blogs about migration, population dynamics, and regional economics at In a State of Migration.