Highlights

Over the past several years, we have seen some interesting research about how marriages fare when traditional gender roles are upended. Female-breadwinner households seem to have higher divorce rates, for example, and one especially controversial study claimed that couples have less sex when the husband does stereotypically female chores around the house. A competing study a couple years later found the opposite.

The latest addition to this literature is fascinating and thorough, though it addresses a very narrow slice of the population. Using data from Sweden, Olle Folke of Uppsala University and Johanna Rickne of Stockholm University looked to see what happened when married men and women were promoted in two different ways: politically, to mayor or parliamentarian, and in business, to CEO. (In Sweden these are similar accomplishments; to become a mayor or parliamentarian, one must first climb through the ranks of the party.)

The result? Women, but not men, were at increased risk of divorce after receiving a promotion. But among women, those at risk were those who had “adhered to traditional gender roles in the early phase of the relationship.”

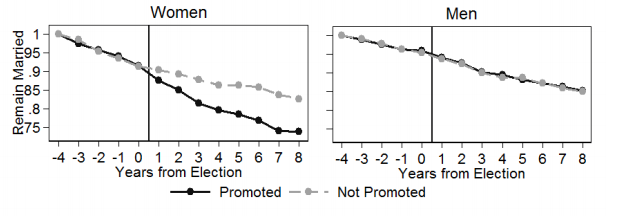

Here are the charts depicting the headline result for mayors and parliamentarians:

Source: Olle Folke and Johanna Rickne, "Job Promotion and the Durability of Marriage," Working Paper, Research Institute for Industrial Economics, 2016.

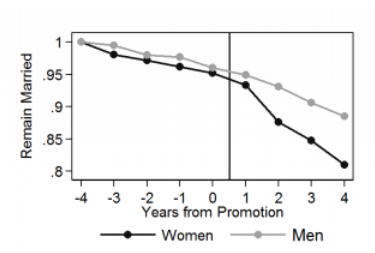

The same pattern emerges for those who won close elections—which are close to a random experiment. And a similar trend emerges yet again for CEOs, though the authors have data only for those who actually received the promotion:

Source: Olle Folke and Johanna Rickne, "Job Promotion and the Durability of Marriage," Working Paper, Research Institute for Industrial Economics, 2016.

On average, these folks are in their 40s or 50s and have been married a decade or two—and they’re already involved in politics or business at such a level that they’d be considered for promotion to the top. Nonetheless, promotions destabilize these marriages when it’s the wives who get them.

Why? Thanks to Sweden’s comprehensive data, the authors are able to slice and dice the numbers a few different ways to find some insights.

One thing that matters, the authors write, is whether the marriage has been gender-stereotypical in the past specifically, whether “the promoted woman (1) is younger by her spouse by [at least four years] and (2) took a relatively larger share of the parental leave. Strikingly, we find no divorce effect in the sub-sample of women in more gender-equal couples.”

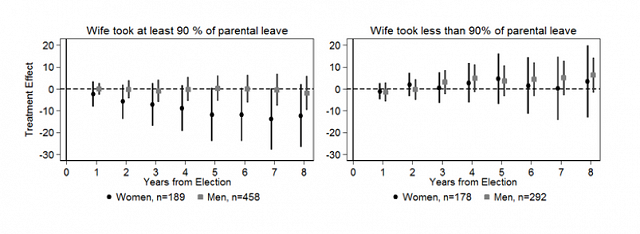

Here’s a striking chart that breaks the divorce effect down by whether the wife took at least 90% of the couple’s parental leave:

Source: Olle Folke and Johanna Rickne, "Job Promotion and the Durability of Marriage," Working Paper, Research Institute for Industrial Economics, 2016.

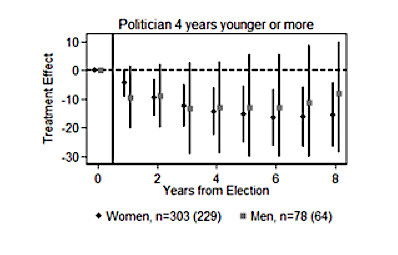

As the authors note, there are several ways to interpret this. One is that “divorce happens when the promotion of a spouse deviates more from his or her expected labor market trajectory"—an idea buttressed by the fact that the (relatively few) men who were four years younger than their partners suffered a divorce effect too, as this chart shows.

Source: Olle Folke and Johanna Rickne, "Job Promotion and the Durability of Marriage," Working Paper, Research Institute for Industrial Economics, 2016.

Another possible explanation is that “women divorce the men who are the least supportive of their careers.” Still another, I would add, might be that these decisions—how to handle parental leave and whether to marry someone of a different age—might reflect underlying personality traits that also affect divorce decisions.

It also seemed to make a difference whether the promotion made the husband or wife earn at least 60% of the household’s income, though the authors caution of low sample sizes regarding this point. Women were more likely to divorce if they became the dominant earner, while men were less likely to divorce if they did.

These findings are narrow enough that they’re not really actionable in everyday life—you shouldn’t avoid marrying someone of a certain age, or structure your parental leave in a certain way, on the off chance that your decision today could make a promotion to the top of your field bad for your marriage years in the future.

But the study advances our understanding of the broader issue of gender roles in a way that challenges traditionalists and liberals alike. A promotion at work damages marriages for women but not men, it suggests—but that’s true only for marriages that have been gender-traditional in the past.

Robert VerBruggen is a deputy managing editor of National Review.