Highlights

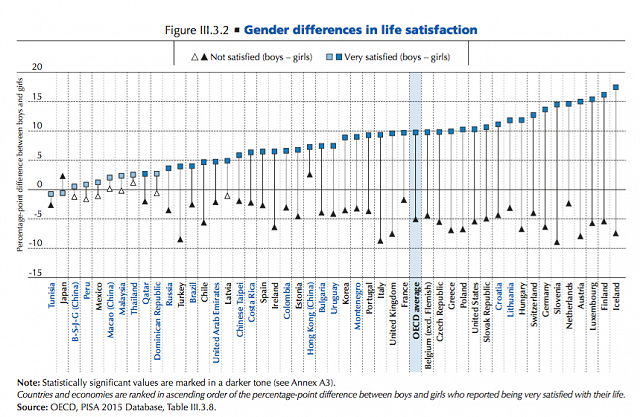

Why are boys happier than girls? That might be one question you would ask after reading the most recent report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) analyzing 2015 PISA scores and the surveys that were done of the students who took the test. In addition to measuring how students around the world are doing in math or science or reading, the researchers also looked at the big question of “life satisfaction.” And it turns out that 39% of 15-year-old boys said they were very satisfied with their lives, but only 29% of 15-year-old girls said the same.

It is important to note first, as the authors do, that these numbers did not always correlate with the gender differences in life satisfaction of adults. In other words, a country might have a higher percentage of happy women than men even if they didn’t have a higher percentage of happy teenage girls than happy teenage boys. American women, for instance, are happier than their male counterparts.

But back to the 15-year-olds. This is a snapshot in time, and it’s simply possible that the life of a boy at this age is more satisfying than the life of a girl. I think if you ask this question of 12-year-olds, you might get a different answer. At that age, girls often seem more confident, less consumed by peer pressure, and boys seem more awkward and out of place.

There are those who will look at this survey and assume that the reason girls are not as happy is due to sexism or some kind of discrimination. What’s odd, though, is that many of the countries that we think of as the most egalitarian in terms of their attitudes toward gender contain some of the biggest gender gaps in happiness. According to the report: "In Austria, Finland, Iceland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Slovenia—all countries where students’ satisfaction with life is higher than the OECD average—the difference in the share of boys and girls who reported high life satisfaction is greater than 14 percentage points in favour of boys” (see figure below).

Source: OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students' Well-Being, OECD Publishing, Paris.

What is going on in these countries that might be causing such large discrepancies? One possibility is that adolescence is a time of great confusion for both boys and girls, and in countries that have blurred the lines between men’s roles and women’s roles, teenage girls might not be so sure what they are supposed to do with themselves.

The researchers did note that there is very weak correlation between performance on the test and life satisfaction. So even gender differences in test performance are unlikely to account for differences in how happy the students actually are with their lives.

The gender gap in happiness among students in more egalitarian countries does seem to echo one trend in the United States. While women here are happier, their happiness has been declining, and some have traced this to changing gender roles. Perhaps having more choices does not necessarily mean being happier.

In a paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers looked at the Monitoring the Future data set (which surveys American high school students) and found a more specific reason for girls’ lower life satisfaction in this country. Stevenson and Wolfers explain:

We find that teenage girls have attached greater importance to a number of domains both absolutely, and relative to that of boys. Moreover, they are increasingly dissatisfied with the amount of free time that they have available, perhaps as a result of their increasing desire to excel in their roles in the community, in the labor force, and in their families.

In other words, while a more egalitarian society offers women more opportunities, many women—especially younger ones trying to learn their way—see those as greater demands. The authors also note that as women’s opportunities for advancement in the workplace grew, the group to whom they compared themselves changed. Life satisfaction is not something we report in a vacuum. So perhaps women are less happy because we are comparing ourselves to men rather than simply to women. Or it may simply be that women’s expectations have been raised to unrealistic levels. The disappointment in not being able to “have it all” can create dissatisfaction.

For 15-year-olds, these issues may not be manifesting themselves just yet, but they may have a growing awareness of what’s to come.

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a senior fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum and a columnist for the New York Post. Her most recent book is The New Trail of Tears: How Washington Is Destroying American Indians.

Editor’s Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.