Highlights

- The child tax credit, in general, is not as popular as one might think—even in questions that don't mention the taxes needed to pay for it, it never manages a majority. Post This

- Giving a child credit to all taxpayers (CTC1) is reasonably popular with Americans of all persuasions, while giving more money to the wealthy (CTC2) is unpopular on both sides of the aisle. Post This

Everyone is talking about the child tax credit these days. Specifically, a lot of smart people on both sides of the political aisle wish it were more generous.

The credit currently on the books is worth up to $2,000 per child, but it is not available to families with very low incomes, who don’t have enough tax liability to take full advantage of it. During the debate over the 2017 tax law, Republicans Marco Rubio and Mike Lee tried unsuccessfully to make it available to more of these families (specifically, by letting them use the credit to offset all, and not just some, of their payroll-tax liability in addition to their income-tax liability). Mitt Romney recently pushed a proposal with Democrat Michael Bennet to increase the credit to $2,500 for the youngest kids while making much of it “fully refundable,” meaning parents could get it even without any tax liability at all. In an earlier proposal, Bennet and fellow Democrat Sherrod Brown had suggested an even bigger credit, up to $3,600 for parents of young kids, with no limits whatsoever based on tax liability.

So, what does the average person think of all this? The 2019 American Family Survey, a poll covering 3,000 adults from the Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy, tested four different child tax credit proposals (spelled out below). The results give us a sense of how the public—and some key segments of it—see the issue.

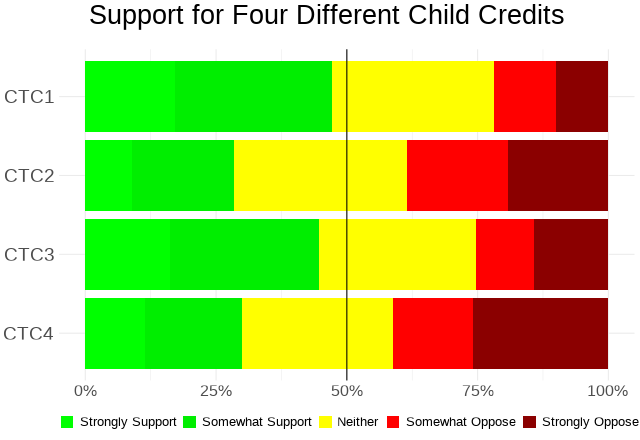

Interestingly, none of the ideas had majority support, but about a third of those answering each question said they had no preference, so some of the proposals had far more supporters than opponents. Here's a chart I made of the breakdowns before we start fleshing out each option, with supporters in green, fence-sitters in yellow, and opponents in red, and a vertical line at 50% to indicate where either side has a majority:

Note: CTC1: All parents who pay income taxes receive credit. CTC2: Parents w/higher incomes receive more.

CTC3: Parents w/lower incomes receive more. CTC4: Flat allowance for all parents regardless of if they pay taxes.

Source: 2019 American Family Survey, Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy/Deseret News

The first question, which I've labeled CTC1, refers to a credit "that would return a set amount of money to all parents with children under 18 who pay income taxes," and it came close to having the support of half the respondents. This conceptualizes the child credit as tax relief rather than aid to parents per se.

CTC2, meanwhile, “would return money to all parents with children under 18, with the amount proportional to what they paid in taxes, so families with higher incomes get back relatively more.” This doesn't map cleanly onto any existing proposal I'm aware of, though it's reminiscent of the old "dependent exemptions" that the 2017 law got rid of in favor of a bigger child credit. (These exemptions allowed parents to reduce their taxable income by a set amount for each child, which is more valuable to wealthier taxpayers in higher tax brackets.) Anyway, it's clear enough that people hate the idea of a government benefit where “families with higher incomes get back relatively more.”

CTC3 is the opposite of CTC2 —it “would return money to all parents with children under 18, with relatively greater amounts going to families who paid less in taxes, so families with lower incomes get back relatively more”—and it's about as popular as CTC1. And CTC4, which bombed nearly as badly as CTC2, would “guarantee a set amount of money sent to each family every month, whether they pay income taxes or not.”

These results are consistent with some observations Josh McCabe made in The Fiscalization of Social Policy: Other countries often have child allowances the public sees as neither tax relief nor welfare, but in the U.S., any child credit has to be one or the other. Nearly half of Americans can support a credit sold as tax relief that’s either broad-based (CTC1) or targeted to the lower-income (CTC3), but an across-the-board handout to parents just for being parents (CTC4) can't even garner one-third support.

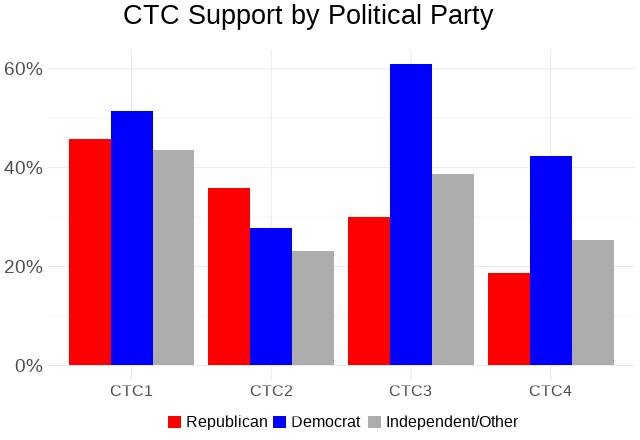

Since Republican and Democratic politicians tend to approach this issue in different ways, with Republicans emphasizing tax relief and Democrats wanting to support poor parents, it's also worth looking to see if Republicans and Democrats agree. For simplicity, I collapsed the five answers down to just two categories—those who supported a given proposal, whether strongly or only somewhat, and everyone else—and cross-referenced them with partisan self-identification. Here are the results:

Note: CTC1: All parents who pay income taxes receive credit. CTC2: Parents w/higher incomes receive more.

CTC3: Parents w/lower incomes receive more. CTC4: Flat allowance for all parents regardless of if they pay taxes.

Source: 2019 American Family Survey, Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy/Deseret News

Basically, giving a child credit to all taxpayers (CTC1) is reasonably popular with Americans of all persuasions, while giving more money to the wealthy (CTC2) is unpopular on both sides of the aisle, though support drops much less for Republicans than for Democrats. The third and fourth options—giving more support to the poor and a universal child allowance, respectively — show the strongest partisan skew, with Democrats twice as likely to support them as Republicans.

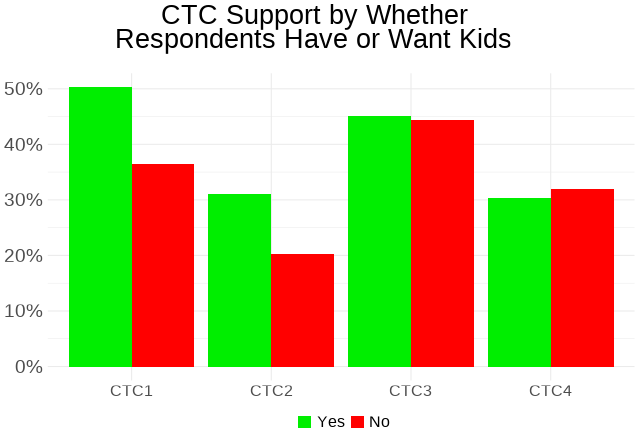

A couple of other traits are salient here as well: A child credit obviously goes only to parents, and the various options differ in terms of how the credit treats people of different income levels.

Here’s how support varies between people who either have or want kids and those who don't (or at least are unsure about whether they want kids in the future). There’s nothing too surprising here, beyond the lack of a gap for the last two proposals.

Note: CTC1: All parents who pay income taxes receive credit. CTC2: Parents w/higher incomes receive more.

CTC3: Parents w/lower incomes receive more. CTC4: Flat allowance for all parents regardless of if they pay taxes.

Source: 2019 American Family Survey, Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy/Deseret News

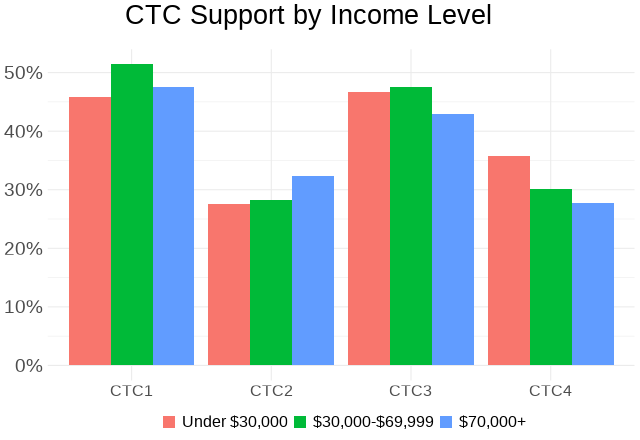

And here it is among three family-income groups that are roughly the same size in the survey, showing some evidence that richer people are more likely to support benefits for the rich and vice versa.

Note: CTC1: All parents who pay income taxes receive credit. CTC2: Parents w/higher incomes receive more.

CTC3: Parents w/lower incomes receive more. CTC4: Flat allowance for all parents regardless of if they pay taxes.

Source: 2019 American Family Survey, Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy/Deseret News

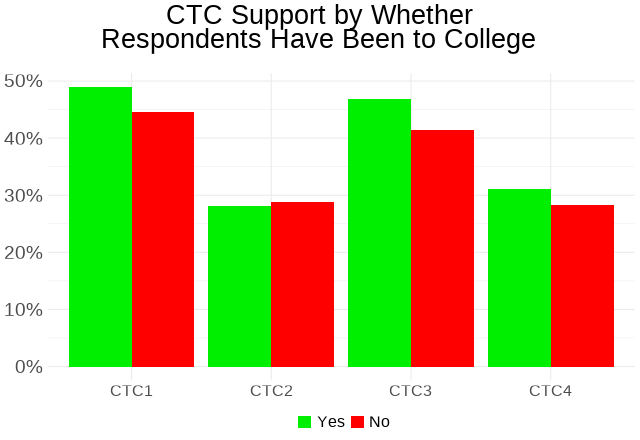

There’s also some evidence that more educated Americans are more likely to support these credits, with the exception of the one that gives more to richer taxpayers (CTC2), though these differences aren’t too dramatic either:

Note: CTC1: All parents who pay income taxes receive credit. CTC2: Parents w/higher incomes receive more.

CTC3: Parents w/lower incomes receive more. CTC4: Flat allowance for all parents regardless of if they pay taxes.

Source: 2019 American Family Survey, Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy/Deseret News

One could slice and dice these data about a million other ways, but I'll stop for now. I think the major takeaways are these: 1) The child tax credit, in general, is not as popular as one might think — even in questions that don't mention the taxes needed to pay for it, it never manages a majority; and 2) despite some energy on the pro-family intellectual right for flat, universal child allowances (CTC4), Republicans and even independents among the general public are really not fond of the idea. Supporters of an expanded child tax credit should give some thought to the role that public opinion will play in any future legislation, and how best to make their case to a skeptical electorate.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.