Highlights

Government initiatives to strengthen families and improve the well-being of children go beyond the controversial relationship education programs whose participants we recently described on this blog. A parallel, less well-known policy initiative has focused on educational programs to support responsible fatherhood. While relationship education programs seek to improve the quality and stability of couples’ romantic relationships, which promotes children’s well-being indirectly, responsible fatherhood programs focus directly on supporting men’s involvement in their children’s lives, including developing men’s parenting and co-parenting skills, as well as improving their employment skills.

As we pointed out in the earlier post, there has been debate about whether these kinds of family-strengthening programs would draw enough interest from families to justify their government funding (in the case of responsible fatherhood programs, that’s about $500 million since 2006 from the Administration from Children and Families). Though some feared the programs would not reach many of the at-risk families targeted by policy-makers, relationship education programs are reaching significant numbers of diverse, lower-income families. What about the responsible fatherhood programs? These have received less scrutiny to date. We reviewed close-out reports from the first wave of responsible fatherhood programs (2006-2011) funded by the ACF’s Office of Family Assistance to get a picture of whom these programs are serving and other interesting details.

The reports show that the responsible fatherhood grantees served more than 341,000 participants in the first five years. The average grantee served 3,410 participants, or about 700 a year. More than 40 percent of the people served were black, about 30 percent were white, and about 20 percent were Hispanic/Latino. Unfortunately, responsible fatherhood grantees did not consistently report participants’ income. However, the available data, covering a minority of participants, show almost half (45 percent) of participants lived below the poverty line.

One interesting finding is that about one in six (16 percent) participants in responsible fatherhood programs were female. Twenty-two programs provided curriculum that combined fathering education with healthy relationship education, and four other programs focused solely on couple relationship education. Also, a few organizations served women in unique situations, such as when the child’s father was incarcerated or when women wanted to improve their relationship or work more effectively with the child’s absent father.

A typical participant in responsible fatherhood programs appears to be a poor, young black male trying to manage a complex family situation.

The men who participated in responsible fatherhood programs often were dealing with complex family situations. We saw this in testimonials from program participants in the reports we examined as well as in a recent qualitative study by ACF’s Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation of 87 men who participated in one of these responsible fatherhood programs. In that study, more than 75 percent of fathers did not live with their biological children. To complicate matters more, the study showed some fathers had multiple children from multiple partners, making child-support and housing issues much more complicated.

So who’s primarily being served by these programs? A typical participant appears to be a poor, young, adult, black male trying to manage a complex family situation.

Why do men come to these programs? In the recent qualitative study we mentioned above, researchers found the main reasons participants entered a program were to be a better father and to get help finding a job. Data from the reports we examined reinforce these findings, showing many fathers come to the programs because they are trying to reenter their child’s life, trying to improve their communication and working relationship with the child’s mother, or sometimes trying to improve their romantic relationship with the child’s mother. By participating in a healthy marriage component of the fatherhood program, fathers hoped to create a more stable family to improve their child’s well-being.

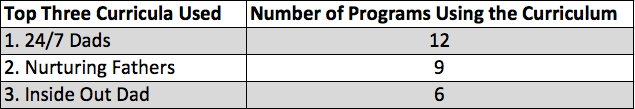

Programs that received federal grants were not required to use established curricula to teach fathers, but many programs did so. The close-out reports we examined showed the most commonly used curriculum was 24/7 Dads, which was developed by the National Fatherhood Initiative. (The ACF provides additional information on program curriculum here.)

Testimonials from the reports showed many participants gained life-changing skills and self-perspective through their curriculum. One participant, speaking about the Inside Out Dad program for incarcerated fathers, said, “If asked what the Inside Out Dad program meant to me, I would say it helped me realize how much I really hurt and embarrassed my children by being a criminal and coming to prison.” For some, the curriculum provided a first-step in truly understanding how their decisions impact their children’s lives.

Evaluation studies of responsible fatherhood programs are still limited, although there are a number of rigorous studies in the works. But we know that grantees are reaching a significant number of at-risk fathers who report that the programs are helpful.

David Simpson is a graduate student in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University. Alan Hawkins is the Camilla E. Kimball Professor of Family Life at Brigham Young University.