Highlights

- Across the globe, actively religious adults tend to be happier and more engaged in their communities, per a new Pew Research Center report. Post This

- The well-established connection between religion and human flourishing should encourage us to more clearly acknowledge, promote, and protect the gifts that shared religious activities bestow on personal and community well-being. Post This

Around the world, adults who regularly attend religious worship services tend to be happier and more engaged in their communities compared to those who attend less frequently or not at all, according to a new report from the Pew Research Center that analyzed several cross-national surveys of adults in over two dozen countries.

In the report, Pew divided survey respondents into three groups: 1) the “actively religious,” or those who not only identify with a religious group but also report attending religious services at least once a month; 2) the “inactively religious” or those who identify with a religious group but attend religious services less often; and 3) the “religiously unaffiliated,” those do not identify with any organized religion. Overall, it found that “people who have a religious affiliation and attend worship services at least once a month tend to fare better on some (but not all) measures of happiness, health, and civic participation.”

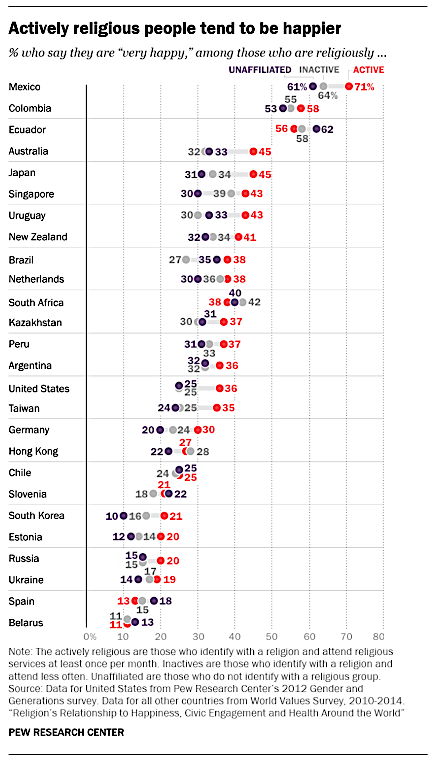

First, the actively religious were happier across the globe. In the U.S., 36% of religiously-active U.S. adults reported being "very happy" compared to one-quarter of both inactive and unaffiliated Americans. In the other countries, as shown in the figure below, “actives report being happier than the unaffiliated by a statistically significant margin in almost half (12 countries), and happier than inactively religious adults in roughly one-third (nine) of the countries.” In fact, Pew found that "there is no country in which the data show that actives are significantly less happy than others."

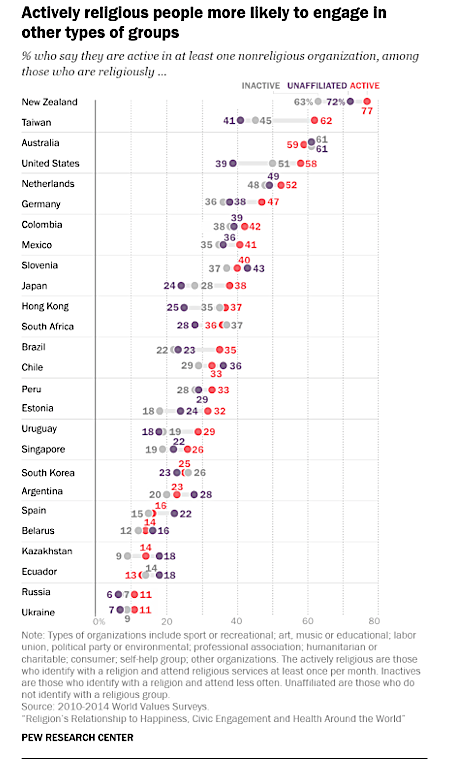

Religiously-active adults were also more likely to report being active in their communities (or in non-religious groups and voluntary organizations, like sports clubs, charity groups, or labor unions). This was especially true in the U.S., where 58% of actively religious adults reported being active in “at least one other (nonreligious) kind of voluntary organization,” compared to 51% of inactively religious adults, and 39% of unaffiliated adults. Pew found a “similar pattern” for 11 of 25 other countries studied.

Additionally, religiously-active adults in the U.S. were more likely to vote in a national election. As for other countries, Pew explains:

“actively religious adults are more likely than “nones” to report voting in national elections in half the countries (12 out of 24) for which data on this measure are available; in the remaining countries, there is not much of a difference. Actives also are more likely than their inactive compatriots to say they vote in nine out of 24 countries, while the opposite is not true in any country for which data are available. ”

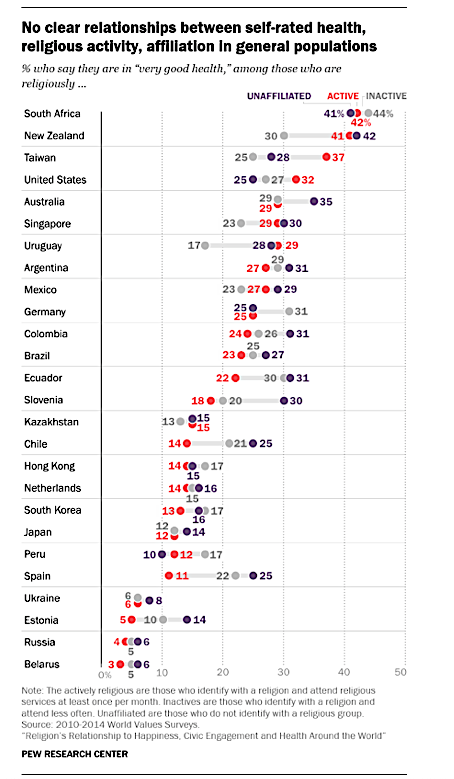

Although religiously-active adults were more likely to report some healthier behaviors, such as not smoking, the results on overall health were “mixed,” with Pew finding no “clear link” between overall self-rated health and active religious participation in most countries around the world, except the U.S., Mexico, and Taiwan.

Importantly, the Pew findings are based on self-rated health. Several longitudinal studies using more objective health outcomes have identified a strong association between religious participation and depression, suicide, and mortality. As Harvard University Professor Tyler J. VanderWeele reported on this blog, “research on this topic at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health links religious service attendance to…longer life, lower incidence of depression, and less suicide.” New research, also from Harvard, has connected a religious upbringing to better health outcomes for adolescents and young adults, including being less likely to use illicit drugs. And numerous studies have found that religious activity is associated with better mental health.

"The teachings, the relationships, the spiritual practices, over time, week after week, taken together gradually altars behavior, creates meaning, alleviates loneliness, and shapes a person in ways perhaps too diverse to document. Such things alter health" — Tyler J. VanderWeele

The Pew report cautions that its findings "do not prove that going to religious services is directly responsible for improving people’s lives." However, in an email to IFS, Dr. VanderWeele said that a weakness of this Pew report is that it is based on cross-sectional data, "which makes it difficult to assess the direction of causality," and he noted that Pew's discussion of the causal effects "is about 5-10 years behind where the research literature currently stands." He emphasized that,

There are now, at least in the United States and Europe, much stronger methodological studies on many of these outcomes. With regard to the outcomes Pew reported on, there are in fact strong longitudinal studies that provide considerable evidence for an effect of religious service attendance on higher happiness, less smoking, less frequent drinking, greater social support, and greater civic engagement.

As for why religious participation is consistently linked to well-being, Dr. VanderWeele addressed this in a chapter in the 2017 book, Spirituality and Religion Within the Culture of Medicine, explaining that religion contributes to health by "shaping behavior, creating systems of meaning, altering one’s outlook on life, building community and social support, supporting moral beliefs, and through an experience of the transcendent."

In light of this research, we should be alarmed by reports of declining religious service attendance, particularly among young people. The Pew report found that only a minority of adults in most countries are “actively religious,” and it warns that “societies with declining levels of religious engagement, like the U.S., could be at risk for declines in personal and societal well-being.” Certainly, the well-established connection between religion and human flourishing should encourage us to more clearly acknowledge, promote, and protect the gifts that shared religious activities, like prayer and worship, bestow on personal and community well-being.

And perhaps, as Dr. VanderWeele put it during a lecture at Harvard University, the research on religious service attendance and health is an “invitation back to the communal religious life” for those who currently identify as religious but do not regularly attend worship. He continued:

Where else today does one find a community with a possibility of a shared moral and spiritual vision, a sense of mutual accountability, where a central task of the members is to love and care one another? The teachings, the relationships, the spiritual practices, over time, week after week, taken together gradually altars behavior, creates meaning, alleviates loneliness, and shapes a person in ways perhaps too diverse to document. Such things alter health.

Alysse ElHage is Editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog.