Highlights

- Slightly more than one-in-five (or about 2.5 million) black men ages 18 to 64 have made it into the upper-third of the income distribution. Post This

- Black men who have a college degree, a full-time job, or a spouse are much more likely than their peers to end up in the upper-income bracket as fifty-something men. Post This

The racial news in America has been sobering in recent years. From Trayvon Martin to Walter Scott, from Ferguson to Charlottesville, one incident after another has cast a pall over race relations in the nation. In fact, the share of Americans who consider racism a big problem has almost doubled in the last decade. Meanwhile, recent research on race—including Raj Chetty and colleagues’ new study showing that black boys’ chance of moving up the economic ladder are much lower than white boys—only makes the picture look worse.

But the negative news about race in general and black men, in particular, is not the whole story. Our new report, Black Men Making It In America, finds that despite the burdens they face—from residential segregation to workplace discrimination to over incarceration—more than one-half of black men have made it into the middle or upper class as adults. This means that millions of black men are flourishing financially in America.

But how many black men have made it, specifically, into the American upper class? In a new analysis of Census data, we find that slightly more than one-in-five (or about 2.5 million) black men ages 18 to 64 have made it into the upper-third of the income distribution.

Notes: Based on adults ages 18 to 64. Income refers to total family income adjusted by family size.

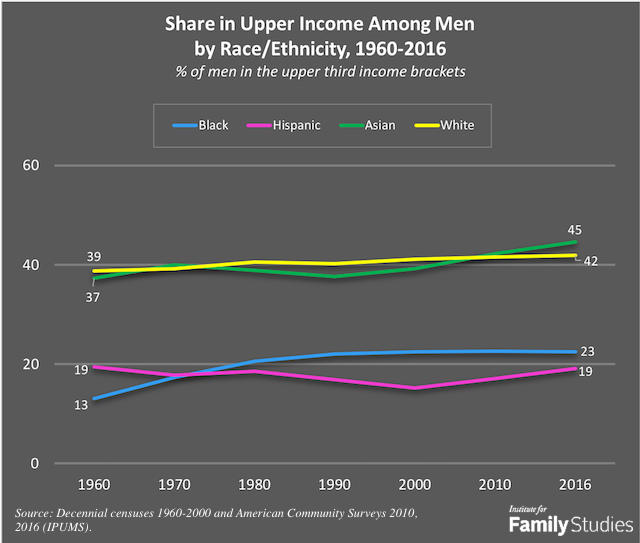

In fact, black men have made marked progress over the last half-century in reaching the upper ranks of the income ladder. The share of black men who are in the upper-income bracket rose from 13% in 1960 to 23% in 2016, according to our analysis. Moreover, poverty among black men has dropped dramatically over the same time, with the share of black men in poverty falling from 41% to 18% since 1960.

What is Fueling Their Success?

Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (1979) that tracks black men from their teenage years to midlife, we find that a majority of upper-income black men in their fifties today are from humble roots. For example, 59% were lower-income when they were teenagers or young adults. And about half of them grew up outside of an intact, two-parent family. Yet, these men made it into the upper class despite the challenges they faced through thirty-plus years of life. What paths did they take to the top?

We identified three major factors that are linked to the financial success of black men in midlife today: education, work, and marriage. Black men who have a college degree, a full-time job, or a spouse are much more likely than their peers to end up in the upper-income bracket as fifty-something men.

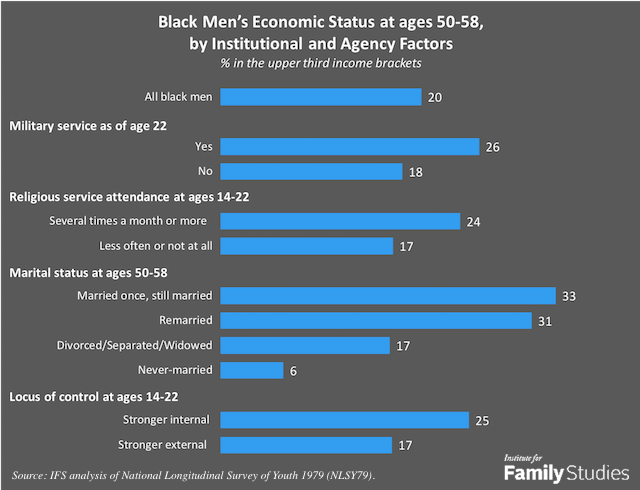

About half of black men with a bachelor’s or higher degree have made it to the top income by age 50, compared with only 14% of high school graduates and 22% of black men with some college education. And more than 3-in-10 married black men (regardless of whether they are in their first marriage or not) are in the upper-income group, compared with only 6% of never-married black men. In a multivariate analysis that includes a range of factors, education, work, and marriage are highly predictive of black men’s economic success.

Moreover, a number of early life experiences are associated with black men’s elevated odds of being financially successful. Black men who served in the military or attended church regularly as young adults are more likely to have made it to the upper class by age 50. The impact of military experience on black men’s success seems to work through its links with black men’s work and marital status. That is, black men who served in the military early in life are more likely to be working full time and to be married later in life.

Having a sense of personal agency also is linked to black men’s success. Black men who believed at a young age that they were mostly responsible for their lives rather than outside forces (measured by a locus of control scale) are more likely to flourish later in life.

Notes: Based on adults born between 1957 and 1964. Income refers to total family income adjusted by family size.

Our story is not entirely positive. Clearly, the racial gap in success is large, with African American men being about 20 percentage points less likely to reach the upper class today compared to white and Asian men. One reason that’s the case is that black men were more likely to have contact with the criminal justice system. In our analyses, early contact with the criminal justice system hurt black men’s chance of being financially successful many years later. After holding education, work, and marriage constant, black men’s contact with the criminal justice system reduced their chance of making it to the upper class by about 70%.

However, focusing only on the negative side of the story for black men has its limitations. First, it renders millions of successful black men, and the paths they have taken to the American Dream, invisible. Second, it can lead to a sense of hopelessness for young black men. As Ian Rowe, the CEO of a charter school network in New York City has noted, with so much talk of “black failure” today, black boys may start to feel “why even bother when the odds are stacked against you?”

In order to engender hope for the next generation of young black Americans, we need to spotlight the many positive stories of successful black men that are out there and identify the routes that these men have taken to rise up the economic ladder. This is especially the case since the majority of black men who made it to the upper class in their mid-fifties came from lower-income households when they were 14 to 22 years old.

To those ends, our new research indicates that one-in-five black men have made it into the upper class, and it suggests that education, work, marriage, and military service provide paths that help black men achieve the American Dream.

Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies and a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center. W. Bradford Wilcox is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia. Ronald B. Mincy is Maurice V. Russell Professor of Social Policy and Social Work Practice at Columbia University and a co-principal investigator of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study.