Highlights

- The research indicates that, on average, the effects of a religious community are profoundly positive. Post This

- Parents who bring up their children religiously can be reassured that, on average, they are creating important psychological and behavioral health benefits that their children will carry with them into adulthood. Post This

Growing up in today’s world can be complicated. Parents are often worried about how their children will navigate the social, behavioral, and developmental challenges of life, especially during adolescence, which can be a particularly difficult time. Our research, which was recently published out of Harvard’s Chan School of Public Health and co-authored by Ying Chen at the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard, suggests that a religious upbringing can profoundly help adolescents navigate the challenges of these years. We also found that a religious upbringing contributes to a wide range of health and well-being outcomes later in life.

Our study used a large sample of over 5,000 adolescents, followed them up for more than eight years, and controlled for many other variables to try to isolate the effect of religious upbringing. We found that children who were raised in a religious or spiritual environment were subsequently better protected from the “big three” dangers of adolescence.

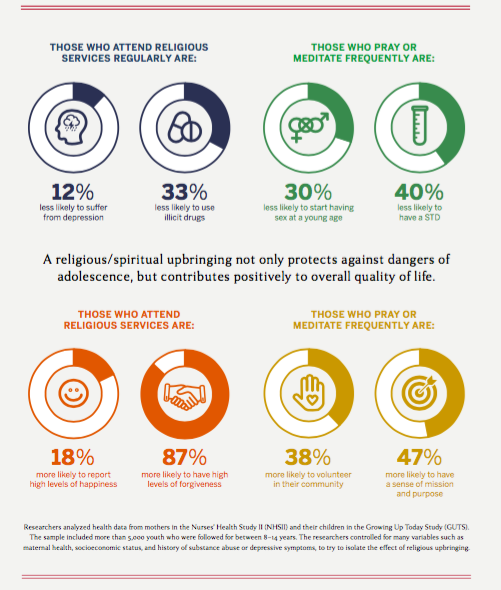

For example, those who attended religious services regularly were subsequently:

- 12% less likely to have high depressive symptoms

- 33% less likely to use illicit drugs

Those who prayed or meditated frequently were:

- 30% less likely to start having sex at a young age

- 40% less likely to subsequently have a sexually transmitted infection

Moreover, a religious upbringing also contributed towards to a number of positive outcomes as well, such greater happiness, more volunteering in the community, a greater sense of mission and purpose, and higher levels of forgiveness. For example, those who attended religious services were subsequently:

- 18% more likely to report high levels of happiness

- 87% more likely to have high levels of forgiveness

Those who prayed or meditated frequently were subsequently:

- 38% more likely to volunteer in their community

- 47% more likely to have a high sense of mission and purpose

These are relatively large effects across a variety of health and well-being outcomes. Religious practice and prayer or meditation can be important resources for adolescents navigating the challenges of life.

(Chart used with permission from the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard.)

Some might wonder if these associations truly imply that religious and spiritual practices really cause the health and well-being outcomes. Could it be that those who are already happier or who refrain from drug use, are those who are naturally drawn to religion? Might this explain the associations, rather than a causal effect of religious and spiritual practices on subsequent health and well-being?

We attempted to deal with this issue in several ways. First, the religious upbringing variables were measured 8-14 years before the health and psychological well-being outcomes were evaluated. This more rigorous longitudinal design helps establish the temporal ordering of the relationships, and in this way is superior to most prior studies on this topic, which used cross-sectional data (where everything is measured at the same time). Second, wherever possible, we controlled also for the health and psychological characteristics of the adolescents at the time that the service attendance and prayer/meditation was assessed to try to rule out that it was just positive health or psychological states that was leading to greater religious practice. Third, we controlled for numerous other social, demographic and health characteristics at the time of adolescence to try to rule out that these might explain the relationship. Finally, for each and every outcome examined, we reported a new measure, called the E-value, that assesses how robust or sensitive results are to potential unmeasured variables, and thereby helps evaluate the evidence for causality (see endnote below for examples).1 Although it is difficult to prove “causality,” with the sort of observational data we used, the evidence for the effects of a religious upbringing on some of the health and well-being outcomes is, in fact, here quite strong.

But what are the implications of this research? Here, some additional nuance is probably needed. People generally do not make decisions about religious involvement based on health, but rather on beliefs, values, truth claims, relationships, experiences, and so forth. However, for parents and children who already hold religious beliefs, such religious and spiritual practices could be encouraged both for their own sake, as well as to promote health and well-being.

Modern life is very busy, and it can take a strong commitment to participate in a community, or to set time aside for prayer or meditation, and to encourage children in these practices. Our study suggests that for those who already hold these beliefs, setting such time aside in parenting, and for adolescents to engage in these practices, is worthwhile.

Although it is difficult to prove “causality,” with the sort of observational data we used, the evidence for the effects of a religious upbringing on some of the health and well-being outcomes is, in fact, quite strong in our study.

There has also been some concern expressed in various settings about whether being raised religiously might be harmful. The sexual abuse scandals in the Catholic Church have led some parents to question whether their children should be present in such settings at all. Certainly, these instances of sexual abuse need to be addressed, and some progress has already been made in that regard, though more work still needs to be done. Those who covered up the abuse cases need to be held accountable; and for the victims of abuse, their harmful and horrifying experiences need to be acknowledged and addressed.

Our own research is based on averages: the statistics average over all of the positive experiences and also all of the negative experiences, too. The research indicates that, on average, the effects of a religious community are profoundly positive. This does not in any way excuse the incidents of harm by religious leaders or institutions, but it does make clear the substantial benefits of religious practice overall. Ceasing those practices will, on average, likely lead to worse health and well-being outcomes.

Some have gone even further in expressing concern that a religious upbringing may be harmful. Recently, the Oxford biologist Richard Dawkins likened a religious upbringing to child abuse, going so far as to claim in a lecture that, “Horrible as sexual abuse no doubt was, the damage was arguably less than the long-term psychological damage inflicted by bringing the child up Catholic in the first place.” The point was reiterated in his book The God Delusion (p. 356), and he has even gone on to write another book on Atheism for Children, which he plans to publish this fall.

Our study shows that on a number of important health and well-being outcomes, Dawkin’s claim just isn’t true. It is disrespectful of those who have experienced sexual abuse, and it is just plain wrong with regard to the average effects on health and well-being that religious practice brings. Religious upbringing is of positive benefit for many health behaviors and psychological well-being outcomes. Before making his claims, it would have been good if Dawkins, the scientist, had actually looked at the science. At the very least, parents who bring up their children religiously can be reassured that, on average at least, they are creating important psychological and behavioral health benefits that their children will carry with them into adulthood.

Questions are sometimes raised as to why these positive effects are present and why they are so substantial. This is a more difficult question and goes beyond what we have in the data. My own speculation would be that, for religious service attendance, we observe these effects, in part, because of the benefits of a shared set of beliefs, and practices, and values; and also, because the adolescents have other adult members of their community, beyond their parents, who can serve as mentors and role models. As for the positive effects of prayer and meditation, as I recently shared with IFS, my speculation would be that an integrated spirituality gives rise to an experience of God or of transcendence so that an adolescent need not turn to drugs or risky sexual behaviors in their search for something more. Moreover, that experience of God may fundamentally make a person more other-oriented, leading to greater volunteering, forgiveness, and a sense of mission, and these things ultimately make one happier and protect against depression. Adolescence is a particularly critical time of development and self-understanding, and the establishing of these practices may shape health and well-being throughout life.

Too often in public health, we do not think very much about religious community or parenting practices. However, the results of our new study suggest fairly substantial positive effects on a number of different health and well-being outcomes. Religious practices, such as attending religious services and engaging in prayer, do shape the health of populations and need to be discussed and considered more frequently. Religion and spirituality are important resources for parents and adolescents alike.

Tyler J. VanderWeele, Ph.D., is Professor of Epidemiology in the Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Harvard School of Public Health, a faculty affiliate of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science, and Director of the Program on Integrative Knowledge and Human Flourishing at Harvard University.

1. For example, we reported in our study that for an unmeasured variable to explain away the association between religious service attendance and subsequent volunteering, that unmeasured variable would have to be associated with 1.9-fold higher service attendance, and 1.9-fold higher volunteering, above and beyond everything we already controlled for (which was already a lot). It would thus take quite a lot of confounding to explain away that result. Similarly, to explain away the association between prayer/meditation and the much lower likelihood of subsequently have a sexually transmitted infection, an unmeasured variable would have to be associated both with a 2.7-fold higher likelihood of prayer and a 2.7-fold lower likelihood of a sexually transmitted infection to explain away the results.