Highlights

Editor’s Note: The following by Wendy Wang and W. Bradford Wilcox is the first response in the Institute for Family Studies' symposium on David Brooks' new essay on the nuclear family. We will be publishing more responses to David Brooks throughout this week and next week.

In his new Atlantic essay, David Brooks contends that the model of “a married couple with 2.5 kids” was an anomaly in the 1950s and 1960s, and that this nuclear family model is no longer working for many Americans, especially those who are less privileged. To address our family crisis, Brooks argues we need to break out of the nuclear-family-is-best mindset and “thicken and broaden” family relationships by incorporating extended families and “families of choice” (e.g., friends, co-religionists, and other voluntary groups living together) as better ways to raise children.

We do not know much about forged families given the limited data, but today, Brooks’ strategy of relying on extended family appears to be most appealing to Americans who have not been able to forge a stable marriage of their own. According to our new analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Pew Research Center, men and women are most likely to live with and rely upon their own parents when they are divorced or have never married. And, contrary to the more optimistic gloss Brooks puts on such multi-generational arrangements, adults who live with extended families are not necessarily happier.

Here are three data points on extended family relationships in America today:

1. A majority of Americans with children who live with extended families are not married.

The demographic profile of multi-generational families with kids suggests that a majority of adults with children in this arrangement (65%) are either never married (46%) or divorced, separated or widowed (19%), according to our analysis of Census data.

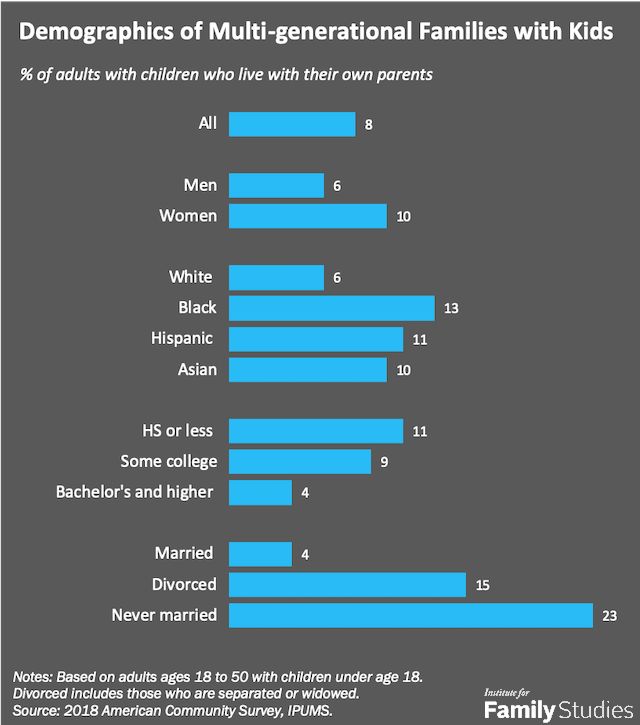

Adults with children who live with their parents are also disproportionately non-white. About 41% of parents who live with extended families are white, compared with 58% of parents who do not live with their parents. Education levels of parents in multi-generational families are somewhat lower: 19% of parents in this setting are college educated, compared with 37% of parents who do not live with extended families.

Raising children with extended families is not common in America. Overall, 8% of Americans ages 18 to 50 with children live in the same household as their parent(s). The share of never-married parents in this living arrangement is much higher than others. Nearly a quarter of never-married adults with children (23%) live with their parents, compared with 4% of married couples.

Multi-generational living also differs by race/ethnicity. Minority families with kids are about twice as likely as whites to have grandparents in the house. At the same time, parents living in a multi-generational household is rare among those with a college education (4%), but more common for those with a high school or less education (11%).

2. Intergenerational transfers happen more often between never-married adults and their parents.

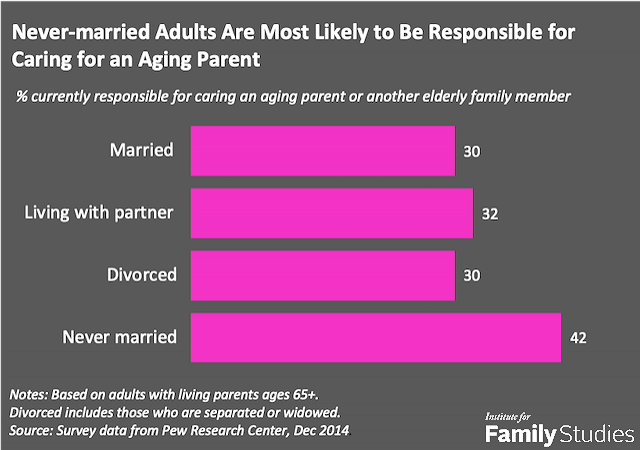

A plurality of never-married Americans with parents ages 65 and older (42%) said that they are currently responsible for caring for an aging parent or elderly family member, according to our analysis of data from a 2014 Pew Research Center survey. Among married adults with older parents, only 30% said so. The share among divorced adults or those living with a partner is also lower.

The responsibility for elder care varies by race/ethnicity. Among adults whose parents are 65 years or older, Hispanics (41%) and blacks (38%) are more likely than whites (29%) to say they are responsible for caring for an aging parent or another elderly family member. (The sample size for Asians was too small to analyze).

Gender also makes a difference. Women are more likely than men to say that they are the caregivers for their aging parents or other elderly family members (35% vs. 28%).

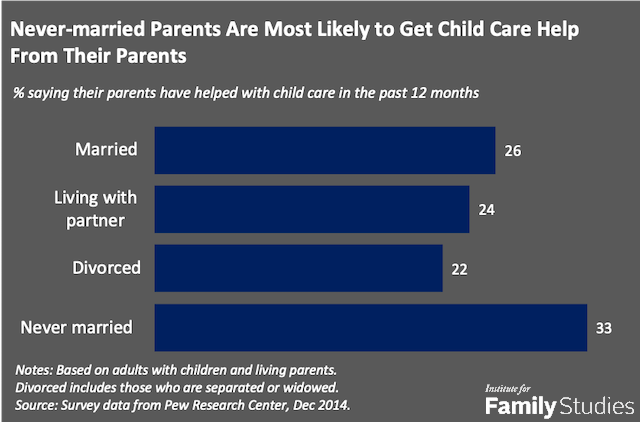

On the other side, adults with children often benefit from the help provided by their parents, especially in terms of child care. In this case, never-married adults with children are more likely to get child care help from their own parents than other adults with children. One- third of never-married parents said that their parents have helped them with child care in the past 12 months, compared with 26% of married parents, 24% of cohabiting parents, and 22% of parents who are divorced, separated or widowed.

Receiving child care from grandparents varies by the education of the adults, but in a different direction. College-educated adults with children (33%) are more likely than those with high school or less education (20%) to have received child care help from their parents in the past 12 months.

3. Adults who live with their parents are less happy than others.

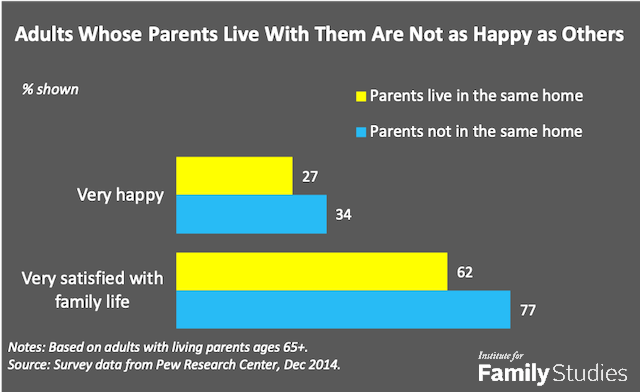

For adults with parents ages 65 and older, the same Pew Research Center survey also asked whether their parents (or stepparents) lived with them in their home for most of the year. Our analysis shows that adults who live under the same roof as their parents are less happy in general and not as satisfied with their family life as others who do not live with their parents.

The sample size of adults whose parents live with them is not big enough for us to break down by demographic characteristics. But this initial finding suggests that, at least from the adults’ perspective, living with an elderly parent may be challenging. Or it could be that adults who are more distressed are more likely to live with their elderly parents.

The story may be different for young adults ages 18 to 34, the group who moved back home during the recession but is now more likely to live with their parents than to live in their own home (with either a spouse or cohabiting partner). We don’t currently have data on how young adults feel about living with their parents, but other research has suggested that parents are generally happier when their adult kids move out of the house. In general, then, the data does not indicate that multi-generational living is linked to more happiness.

This review of demographic and attitudinal data gives just a glimpse into extended families where children are being raised and how generations of modern-day Americans interact and feel. The data suggest two conclusions about David Brooks’ article, “The Nuclear Family Was Never Going to Last.” First, unmarried and especially never-married men and women with children are disproportionately more likely to live with and depend upon their older parents (never-married adults are also more likely to shoulder the responsibility of caring for their aging parents). But it would be a mistake to conclude, at least from the data we currently have, that this extended family model is necessarily a happier one than the nuclear model.

Wendy Wang is the director of research for the Institute for Family Studies. Bradford Wilcox, professor of sociology at the University of Virginia, is a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.