Highlights

- Marriage produces a bigger income premium among less well-off women; higher up in the income distribution, everyone is a little more alike. Post This

- Having been a single mother has lasting effects on a woman’s income as she moves from adolescence and young adulthood into middle age. There is no comparable disparity for married mothers. Post This

- Married mothers have far higher incomes than divorced or never-married mothers. Similarly, these income disparities grow as women age out of adolescence and young adulthood. Post This

Incomes grew steadily for all families in the decades prior to the Great Recession, but the strongest gains belonged to married parents. Having two incomes rather than one goes a long way towards explaining prosperity. Another part of this story is the human capital enjoyed by married mothers. While all mothers have more education and job experience than they used to, married mothers continue to enjoy a strong advantage in labor market qualifications. These resources translate into higher incomes, but not equally. Married and divorced mothers reap relatively similar levels of returns to their demographic and social characteristics, while never-married mothers fare far worse.

The differences by family structure are substantial. Women who give birth out of wedlock suffer from pervasive disadvantage that cannot be explained by their basic social and demographic attributes. They work less. When they do work, they make less money. A high school or college education provides lower economic returns than it does for married or divorced mothers. Never-married mothers’ incomes increase more slowly with age. Even the impact of children, although modest for all mothers, is less strongly related to income than it is for married and divorced mothers.

Previous chapters [in our book] are based on the Current Population Survey (CPS), which offers a series of snapshots of motherhood in America. These data show how motherhood is changing as new generations of women become parents. Since the CPS interviews new respondents with every survey cycle, it cannot tell us about the long-term effects of divorce and out-of-wedlock birth on individual women’s incomes. In other words, the CPS does not allow us to determine whether specific individual mothers have bettered themselves economically, or instead, if different kinds of women are now becoming single mothers.

[We] seek to answer these questions using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth’s (NLSY) 1979 cohort. The NLSY allows us to follow a sample of young women as they became mothers, and thereafter into middle age. By tracking women over time—and, notably, approximately over the same years as the CPS participants we looked at in earlier chapters—we can learn whether differences between married, divorced, and never-married mothers persist as these women move from young adulthood into their 30s and 40s. We also hope to learn more about why never-married mothers receive poor returns to their human capital. The NLSY allows us to track women before they become mothers, so we can explore the possibility that single mothers suffer disadvantages throughout their lives.

Women who give birth out of wedlock suffer from pervasive disadvantage that cannot be explained by their basic social and demographic attributes.

A brief reminder about the NLSY sample: our analysis is based on the slightly over 4,000 mothers or future mothers between the ages of 14 and 22 initially interviewed in 1979. They were polled annually through 1994 and biennially thereafter. The last year of data analyzed here was collected in 2018. At that point, 57% of the original sample was still participating in the survey.

We start off by looking at income differences among the mothers in our sample, then explore issues related to family formation and dissolution, such as the age at which women first became mothers. We then examine characteristics of the parents of mothers, to see if there are systematic differences in the types of families in which married and single mothers were raised. Finally, we examine the characteristics of these women themselves, including education, other measures of cultural capital, and living arrangements.

To examine changes over time, we classify mothers as married, divorced, or never married in each year of NLSY data available to us. We also rely on information collected in the inaugural 1979 survey to ascertain whether women married or became mothers in earlier years. We employ two different measures of family structure: current marital status and one-time marital status. Current status refers to the marital status of mothers in any particular year. This allows us to examine the characteristics of, say, all mothers in the data set who are married in 1990. One-time status lets us identify women who have ever been married, divorced, or never-married mothers, even if their marital status subsequently changes. Unless otherwise noted, having ever been a never-married mother supersedes married and divorced motherhood. In other words, a woman who gives birth out of wedlock before marrying is identified as a never-married mother. She is still characterized as a never-married mother even if she eventually gets divorced. Similarly, a woman who marries, has children, and then dissolves her marriage is treated as a divorced mother.

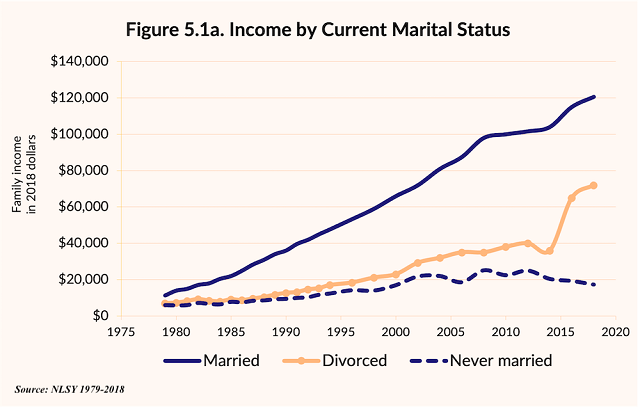

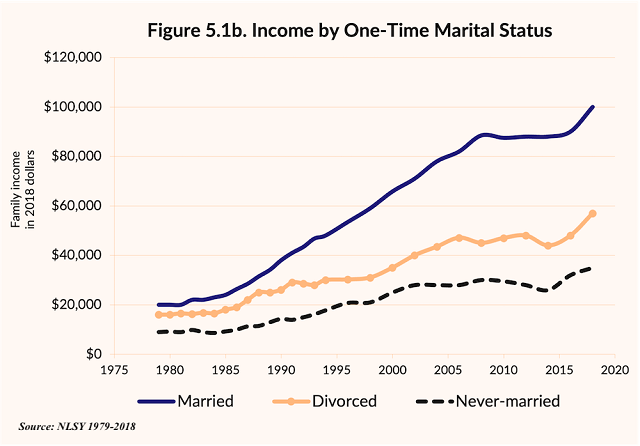

We start by looking at income. Figures 5.1a and 5.1b contrast median family incomes in 2018 dollars both by current family structure (Figure 5.1a) and according to whether women have ever been married, divorced, or never-married mothers (Figure 5.1b). As would be expected, married mothers have by far the highest incomes, followed by divorced and then never-married mothers. This is true across all survey years. The Great Recession aside, all mothers make more money as they get older, but the age gradient is much steeper for married mothers than for their divorced and never-married contemporaries. Married mothers, who started out with median family incomes of around $20,000 in 1979, experienced nearly continuous growth and they broke six figures in 2010. It is generally assumed that job experience and tenure will produce higher incomes as people move from young adulthood into middle age, but our results show that this assumption really only holds for married mothers.

Divorced mothers had incomes somewhat lower than married mothers in 1979, but by 2010 they were only making around $38,000. Subsequent large income gains may be the product of more selective samples. The youngest NLSY mothers in 2010 are 45 years old and mostly have older offspring at home—who are less likely to make it difficult for their mothers to work.

Never-married mothers also experienced income gains in the early 2000s, nearly catching up to divorced mothers, but these evaporated with the Great Recession. Over the 40 years of NLSY data, these mothers have achieved only modest income growth. The story begins early on, given the low incomes in the early years of the NLSY for women classified as never-married mothers.

Looking at current marital status only tells part of the story, given the conditions under which women enter and exit motherhood. Few women become married or divorced mothers as teenagers. In addition, the women who remain mothers in the most recent survey waves aren’t typical either: they had children later in life. For some women, especially married mothers, this reflects delaying childbearing until out of school and ensconced in careers. And given that most women who have children out of wedlock do so while relatively young means that never-married mothers in 2018 are highly atypical.

For these reasons, we turn to the relationship between one-time marital status and income shown in Figure 5.1b. For both divorced and never-married mothers, the similarities between current family structure and ever having experienced single motherhood are striking. Incomes are consistently lower for women who are currently single mothers (Figure 5.1a), which accords with the results presented in previous chapters, but these data show only slightly higher incomes, gains of about ten or fifteen thousand dollars higher, if they have ever been divorced or never-married mothers (Figure 5.1b). Having been a single mother has lasting effects on a woman’s income as she moves from adolescence and young adulthood into middle age. There is no comparable disparity for married mothers, as usually the only way they can stop being married mothers—without becoming divorced mothers—is by emptying the nest. This is what ultimately explains the higher income peak for married mothers in Figure 5.1a ($120,000) compared to Figure 5.1b ($100,000). Women who are still married mothers in 2018 are a selective group who had their children later in life.

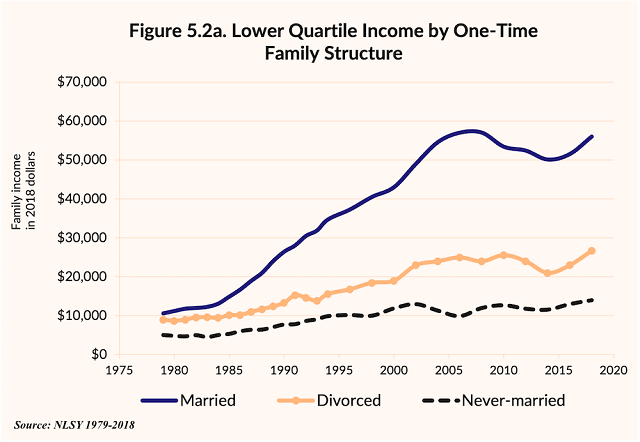

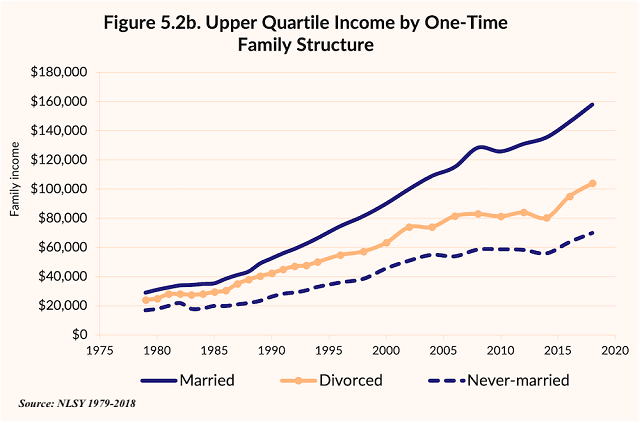

It’s also worth looking at the extent to which lifetime income differences between married, divorced, and never-married mothers persist at different parts of the income distribution. Due to its smaller sample size, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth is less useful here than the CPS. Still, the NLSY sample is large enough to contrast married, divorced, and never-married mothers at the lower (Figure 5.2a) and upper (Figure 5.2b) quartiles. Generally speaking, these figures look quite similar to Figure 5.1b. In both panels, married mothers have far higher incomes than divorced or never-married mothers. Similarly, these income disparities grow as women age out of adolescence and young adulthood.

Two trends in Figures 5.2a and 5.2b are worth noting. The first concerns the relative advantage of married motherhood for women in the lower income quartile. Although the absolute difference in income between married and divorced mothers is similar in the upper and lower quartiles, the difference represents a much larger proportional income boost for lower quartile married mothers. Marriage, therefore, produces a bigger income premium among less well-off women; higher up in the income distribution, everyone is a little more alike.

The second noteworthy pattern in Figures 5.2a and b concerns the faltering finances of married mothers in the lower quartile. Their incomes peaked in 2005 and have since declined, experiencing more precipitous losses than any of the other mothers in the sample. Divorced and never-married mothers didn’t experience big losses in the wake of the Great Recession. Nor did the better-off mothers in the upper income quartile. There is some recovery post-recession for lower quartile married mothers, and perhaps more years of data collection would produce a return to their original income trajectory. Finally, we note the substantial difference in how lower and upper quartile families experienced the Great Recession.

Why do one-time single mothers remain comparably impoverished? This chapter overviews the individual and family characteristics associated with marital status over the life course. Perhaps most noteworthy is the lack of human capital for single mothers. Even as they get older and sometimes marry or remarry, single mothers have less education, and in the case of never-married mothers, less job experience. These women also come from less advantaged families. Furthermore, unmarried mothers suffer from lasting disadvantages paradoxically related to marriage. Women who give birth out of wedlock have disproportionately low rates of marriage and, if they do marry, high rates of divorce. While remarriage is one way for single mothers to lift their incomes, divorce rates are notoriously higher for second marriages. Thus, even if single mothers get married, they are less likely to stay married. Moreover, unmarried mothers are likely to remain unmarried mothers as they get older. Past a certain point, the odds of marriage for all women, single mothers included, only decline.

A final point to consider here involves sample selection: is there a similar reason for why women both become single mothers and earn less money? If so, these women would have less money even had they not become mothers. There is substantial research that shows these outcomes are indeed linked. Marriage is now most likely among women with good incomes and accumulated wealth. However, the extent to which this relationship applies to single mothers is less clear. For example, previous studies have offered conflicting results on the impact of education on the likelihood that never-married mothers subsequently get married, with some finding that it lowers the likelihood for marriage, while others find no impact. Neither education nor employment appear to have any impact on remarriage rates for White divorcées, although they do increase remarriage likelihood for Blacks. (Though African American single mothers in general have lower marriage rates.) As we will see, unwed mothers have other characteristics that keep them both unmarried and cash-strapped over the long haul.

Nicholas H. Wolfinger is Professor in the Department of Family and Consumer Studies and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah. Matthew McKeever is Professor of Sociology and Department Chair at Haverford College.

Editor's Note: This essay is excerpted from Chapter 5 of the authors' new book, Thanks for Nothing: The Economics of Single Motherhood Since 1980 (Oxford University Press, 2024). It is reprinted here with permission.